The best books of 2016 | Neil D.A.Stewart

It was DEFINITELY the worst of times… Civilian arts editor Neil D.A. Stewart looks back over the last 12 months and gives us his take on the best books of 2016

It was DEFINITELY the worst of times… Civilian arts editor Neil D.A. Stewart looks back over the last 12 months and gives us his take on the best books of 2016

As we look back on 2016, and hope that we’ve squeezed the last of its poison out in readiness for a less painful new year, it’s hard not to query somewhat the point of the arts. Is burying your nose in a novel somehow a dereliction of duty, or a refusal to engage with the real world? And while the lure of pure escapism might be greater at the moment than usual, treating fiction purely as a way to escape a venal and vicious real world seems to me even less defensible than usual. Perhaps that’s why the year’s usual crop of polite, polished, prize-destined literary fiction this year has seemed lacklustre and designed-by-committee. Naming no names, the heartwarming fictive memoir in which personal hardship is at last overcome, with bittersweet results, or the meticulously researched historical novel that at once celebrates and explodes late Victorian fiction – still British literature’s comfort blanket – seem less relevant this year than ever before. Ali Smith alone seems, in Autumn (Hamish Hamilton), to be interested in writing a novel of the ultra-present: the first major British novel of “the Brexit era” will be hard to outdo even if her contemporaries catch her up. And, equally feted and mocked though it was, Ian McEwan’s retelling of Hamlet from the point of view of a foetus with the cerebral capacity of a Shakespearean antihero (but the political concerns, funnily enough, of an Ian McEwan) in Nutshell (Jonathan Cape) at least had the virtue of being a bit nuts.

Some of the best of 2016

And in general, it’s been the weirder, grubbier, quirkier books that have been my reading highlights this year. Two latecomer titles from 2015 set the tone for the year: Michael Cisco’s Animal Money (Lazy Fascist Press – and could there be any more pointed a name for a publisher?) opens with a group of economists travelling to a failing South American country to deliver a presentation on forms of currency exchange they’ve observed in the animal kingdom, moves swiftly on to an attack by a disembodied flying head, and only gets odder from there. Ceaselessly inventive, a coruscating blend of the fantastical, the psychedelic, horror fiction and even the political novel, it was a January read that made much of what else I read through the year seem pallid and unadventurous by comparison. Considerably more mundane, but pushing equally against the limits of what literary fiction can or should be, Anakana Schofield’s short, fragmentary Martin John is a case study of a peculiarly English character, a sadcase psychotic, told in short darts and blurts of prose as he pursues his fixations (including obsessional circuits around Euston Station, the avoiding of words beginning with certain letters, and flashing) and is frustrated by various authorities, real and imagined. It’s a perfect marriage of format and subject matter, and pleasingly grimy.

It’s fair to say any Cremaster fans will delight in George’s surreally comic stories

Equally odd but rather more fun, Jen George’s The Babysitter at Rest continues Dorothy, A Publishing Project’s run of presenting terrific, weird works by woman writers (and, in this instance, garnering a cover quote from Matthew Barney: it’s fair to say any Cremaster fans will delight in George’s surreally comic stories); their best-known alumnus, Nell Zink, returned with her most conventional novel so far, Nicotine (Fourth Estate), which takes flight most appealingly when Zink lets herself run with her characters’ own weirdnesses.

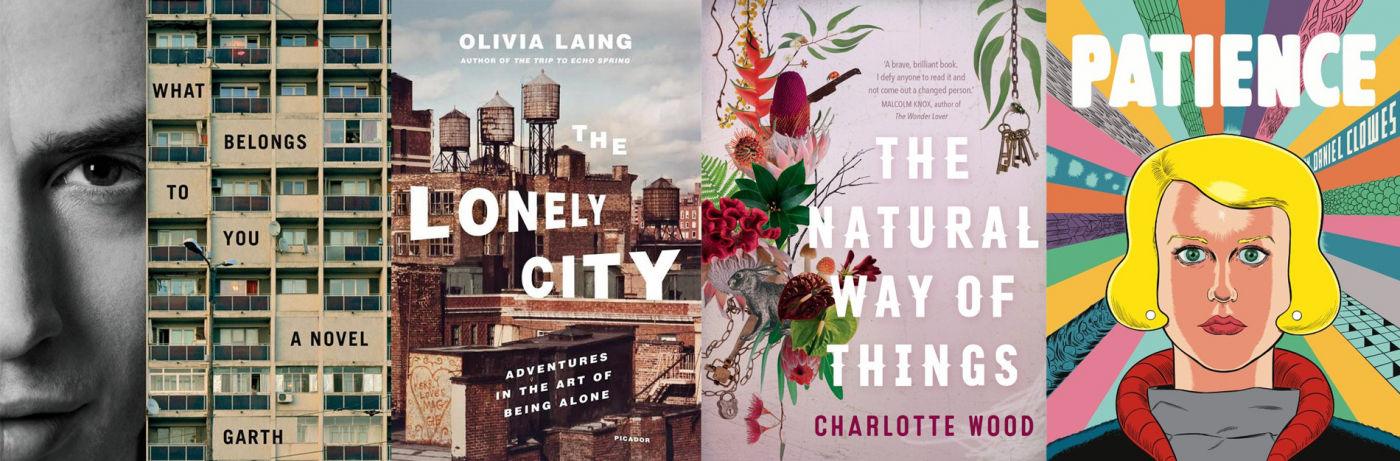

Following his several excellent collections of short fiction, David Means’s Booker-longlisted first novel Hystopia (Fourth Estate) is an anti-history of the Vietnam War that imagines a drug which can wipe soldiers’ memories of the horrors they’ve witnessed. Full of the visceral detail that makes his short stories so memorable, this is an intriguing twist on the historical novel. From the most nightmarish of real wars to the pulpiest of science fiction: Daniel Clowes’s Patience (Jonathan Cape) uses a time travel McGuffin to explore guilt, personal responsibility and – yes – the virtues of patience in a beautiful graphic novel that pays equal tribute to 50s comics and the contemporary confessional memoir.

Surely we have to draw a line now under these waffly, vaguely portentous titles that say precisely nothing about the books they headline?

Drawing from some very twenty-first century horrors, Charlotte Wood’s The Natural Way of Things (Europa Press) posits a scenario in which the women at the centre of the kind of ritualised public shaming fests at which social media excels are abducted and sent to an isolated region at the heart of Australia. A five-minutes-in-the-future thriller that demands to be read in one sitting and lingers long in the imagination, this is one of the books I’ll be buying most as a gift this year; the other, Eileen Myles’s selected poems I Must Be Living Twice (Serpents Tail) is the perfect complement to her reissued novel-memoir Chelsea Girls: it’s a large compendium that only becomes more compelling with each poem.

That unexpected thing, a new great gay novel

In limpid prose and at stately pace, Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs to You (Picador) spins a romance out of an anonymous sexual encounter between a closeted academic and a Bulgarian escort, overcoming a forgettable title (surely we have to draw a line now under these waffly, vaguely portentous titles that say precisely nothing about the books they headline? The title of David Szalay’s otherwise excellent All That Man Is (Cape), for instance, slips the mind as soon as you glance away from the cover) to become that unexpected thing, a new great gay novel. Similarly shining new light on well-mined source material, Yaa Gyasi’s centuries-spanning saga of a Ghanaian family riven apart by slavery, Homegoing (Knopf US, forthcoming from Viking in the UK), is engrossing and – despite the subject matter – surprisingly joyful.

Tama Janowitz

Joyful too, in non-fiction, was Tama Janowitz’s Scream (Dey Street US), a memoir seemingly written in one session under the influence of terrific quantities of caffeine. Fun to read, this might be more fun yet in talking book format, as it’s a great long shaggy dog yarn of the sort you’d love to hear your most raconteurish friend tell over dinner. Significantly more serious, The Lonely City (Canongate) is Olivia Laing’s second masterpiece in a row: a book about how artists – including Andy Warhol, Klaus Nomi, David Wojnarowicz – utilised, fought or even profited by their figurative, personal or geographical isolation to make their work and to live as their truest selves. Like her previous The Trip to Echo Spring, the book also penetrates into its author’s own life: Laing’s own loneliness sparked the idea for the book and, through her hugely empathetic investigations of her subjects, she herself finds, in the end, a new way to live and to be. In the greater and smaller hardships and isolations that face individuals and societal groups in our here and now, to see an artist grapple successfully with these big questions is the very opposite of escapism – rather, it’s a pertinent reminder that in dark times art can still show us how to live. C