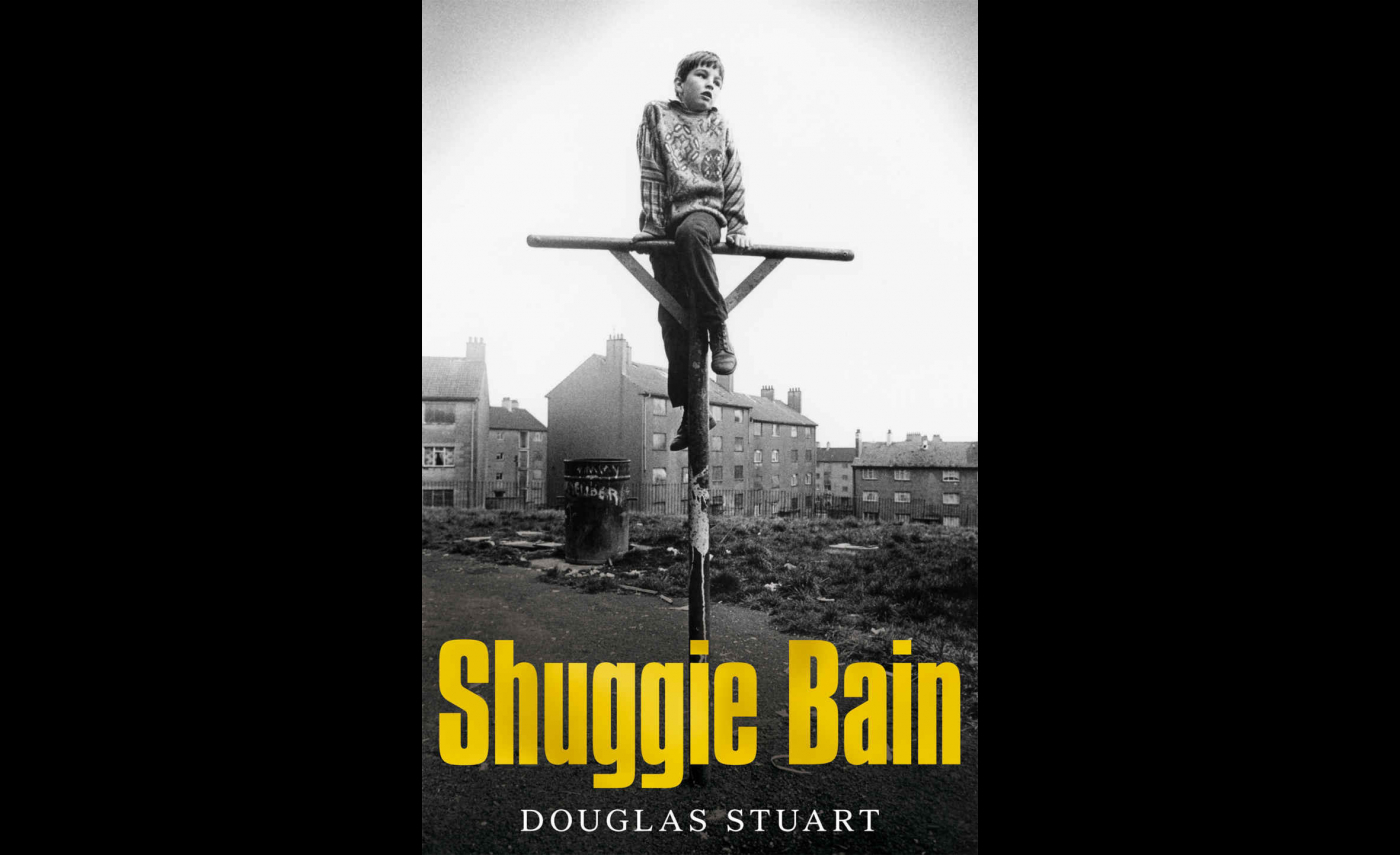

Review: Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

Douglas Stuart’s debut novel is a tour de force of tough times, a jilted love letter to 1980s Glasgow. Neil D.A. Stewart finds glints of optimism and potential in the greyness and grit of a worthy Booker winner

Douglas Stuart’s debut novel is a tour de force of tough times, a jilted love letter to 1980s Glasgow. Neil D.A. Stewart finds glints of optimism and potential in the greyness and grit of a worthy Booker winner

It’s 1992, and in a thin-walled, chill boarding house on the South Side of Glasgow inhabited by dubious characters who shuffle back and forth with bags of clattering cans, fifteen year-old Shuggie Bain is weighing up whether to go to work at the supermarket, or whether he can for once afford to go to school.

From this squalid start, Douglas Stuart’s debut novel unpicks the backstory and circumstances of its protagonist’s life, to show us that this strange existence is a sight better for Shuggie than his fate might have been. Cycling back a decade, Stuart creates a world of dubious “uncles”, alcoholics, violent tempers, frayed nerves, “your new daddy”, of superficial smiles covering venal attitudes. It’s a world in which Shuggie has precisely one ally, one idol: his glamorous mother, “a facsimile of Elizabeth Taylor … the vain and haughty version [from] paparazzi photos” to whom he’ll stay loyal – for better or worse – throughout the grim decade that ensues, through all her romantic travails, neighbourly bust-ups and the disintegration of the rest of their family.

The slagheap – a colourless, treacherous quicksand, the remnants of industry – on which the estate children recklessly play, and in which Shuggie nearly drowns, is this book’s central metaphor

After his father, taxi driver Big Shug, moves Agnes and Shuggie to a new home in unlovely Sighthill – away from the spiky but stable home of Agnes’s parents – he promptly abandons them there, his last act as the family man to strand his wife and child among strangers. It doesn’t take long for Agnes to get the other residents’ backs up – they think she thinks she’s better than them, and waste no time in reminding her she’s an outsider. The boundaries in Sighthill are both literal – territorial – and figurative; heaven help anyone who seems to be trying to better herself, or who gives the wrong answer to the apparently innocuous enquiry about which football team you support. They’re by turns strictly demarcated and fuzzy, murky, porous: when Agnes needs a favour of her neighbour’s family-man husband and the text decorously looks away from how she offers payment, we might wonder who is exploiting whom, and what labels can be applied to either party. The slagheap – a colourless, treacherous quicksand, the remnants of industry – on which the estate children recklessly play, and in which Shuggie nearly drowns, is this book’s central metaphor.

More broadly, 1980s Glasgow is a world of drastic unemployment and social decline, the consequences of Thatcherism – the systematic and ideological destruction of one of Britain’s former industrial powerhouses. With shipbuilding, mining and steelworks all shut down, what’s left behind are dangerous slagheaps, men robbed of agency and income, women who bear the brunt of their frustration and anger. When a tone-deaf new publicity campaign for the city is launched in the mid 1980s, the characters are bewildered by the chosen slogan: Glasgow’s Miles Better. “‘Than what?’ Shuggie asked pointedly.”

For a time, salvation seems on hand in the form of Eugene, who befriends and supports Agnes, behaves kindly to Shuggie and seems, unlike most of the other adults in this book, to have no duplicitous side. His courtship with Agnes is sweet and tentative (there’s a great scene in the Grand Ole Opry, which skewers social pretensions and social fears) and, since it takes place about halfway through the book, we’re in no doubt that it is doomed. As soon as he suggests – pleads – that Agnes take a drink, just one, to be “normal”, the reader’s heart sinks. Like other characters here, he doesn’t quite know when to take his leave, and moves in and out the story after this point, no longer auguring anything good.

It all began to seem a bit overdone. It’s not that mean a city

All this is bleak stuff. Delighted as I always am to see my home city represented in fiction, and to rewalk its geography in prose, I also cavil at depictions of Glaswegian life that are unremittingly grim. When the narrator’s sister is cornered by thugs and threatened with the notorious (and largely apocryphal) “Glasgow kiss” – a knifecut to each side of the mouth – then discovers her attackers to be teenage boys younger than herself, it all began to seem a bit overdone. It’s not that mean a city. Like another Booker shortlistee, Brandon Taylor’s turgid Real Life, Shuggie Bain seems to owe something to everyone’s favourite/least favourite misery saga, Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life; but a novelist’s humourless piling on of ever more gutting depredations and sufferings, a grand guignol of despair over hundreds of pages, can elicit tears of mirth rather than sympathy.

Stuart, fortunately, has an antidote to this: his central character. Wee Shuggie lights up every page he’s on, skipping through the murk with a dolly in one hand (“You’ll be whanting tae nip that in the bud,” more than one character advises Agnes) and a precocious air that originates nowhere in his family. It’s not easy to be a well-spoken child in Glasgow, as I can attest, and I did chuckle aloud at several of Shuggie’s inimitable bon mots, so at odds with the tone of the book and its cast that they seem, to reader and his fellows alike, beamed from a different planet. A particular highlight: overhearing one of the other wifies suggest that his beloved mother is a “working girl”, Shuggie issues an indignant correction: “‘My mother has never worked a day in her life. She’s far too good-looking for that.’” By turns a devoted son and a keen-eyed chronicler of her faults and the world they live in, Shuggie’s unapologetic otherness – he’s not impervious to the insults hurled at him, even if he doesn’t understand what in himself they’re responding to, but he’s entirely and miraculously self-possessed – seems the quality that will equip him to find a way out of the world he’s born into.

I detected a palpable push and pull between Stuart’s control and his debut author’s wish to keep everything

This is a vividly imagined, precisely rendered world, its pushes and pulls and rollercoasters of (mis)fortune rendered in crisp, clean prose. It’s too long a book, and at times I detected a palpable push and pull between Stuart’s control and his debut author’s wish to keep everything: a chapter in which the vile Jinty McClinchy comes to visit – “Ah cannae stop long,” she is still promising hours later – is a terrific standalone setpiece in itself but doesn’t do much for the flow of the book. A sterner editor might have encouraged Stuart to cut back. Oddly, too, for a book that insists on gritty realism, its cast includes not only Jinty but a Keir Weir and an Anna O’Hanna, names better suited to a jocular fable and which sit quite uncomfortably here.

And then there’s Shuggie Bain’s final chapter, which opens the book out and indicates a healthier future for its eponymous character, boarding house blues aside. All this may be a touch too good to be true; but after four hundred pages of disappointments, defeats snatched from the jaws of victory, meaningless deaths and stifling social mores it’s a relief to the reader and to Shuggie alike to step out of the estates and high-rises and breathe in the, well, fresh-ish air of the industry-barren, murkily flowing Clyde. C