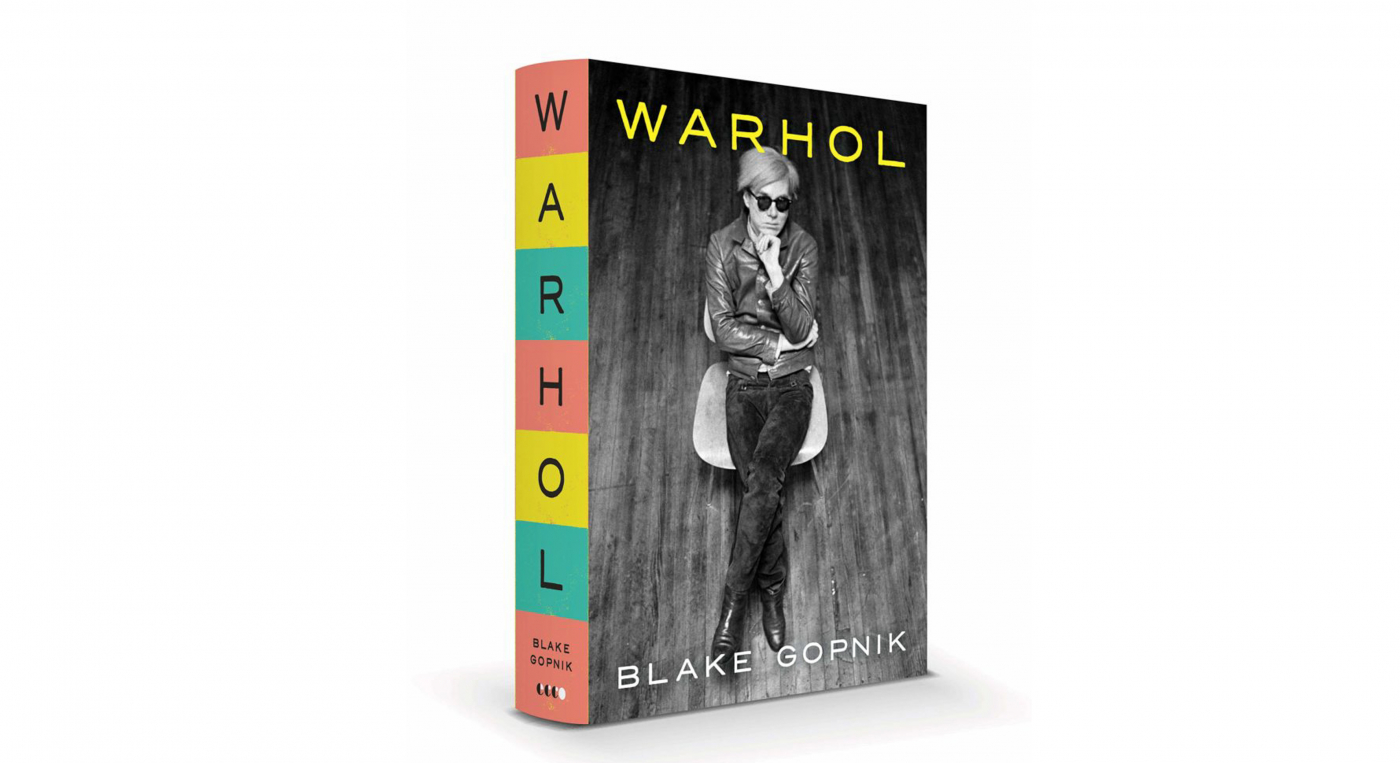

Pop Life | Review: Warhol by Blake Gopnik

A decade in the making, Black Gopnik’s tome on the life and times of Andy Warhol seeks to be the definitive word on the artist – a biography that’s literally “warts and all”

A decade in the making, Black Gopnik’s tome on the life and times of Andy Warhol seeks to be the definitive word on the artist – a biography that’s literally “warts and all”

There have been hundreds of books published on Andy Warhol, and in Warhol, Blake Gopnik has the same dual task as the artist’s previous biographers. He has to decrypt and humanise “Andy Warhol”, the deliberately affectless pop persona that at times would appear to be no more than the sum of its signifiers: a bomber jacket, a silver wig, a pair of dark glasses, a series of studiedly offhand utterances. At the same time, he needs to bring out Andrew Warhola, the purposely suppressed individual behind the mask.

Warhol has a subplot that’s a kind of exegesis of a whole country’s slow opening up to coming out

The accretion of detail about the “real” Andy is one of his methods. Noting, but not derailed by, his subject’s exhaustive chronicling of his own comings and goings, down to “the price of the cabs that he declared as tax expenses”, Gopnik builds a year-by-year, month-by-month account of Warhol’s life so detailed that it’s hard to imagine any major new information ever coming to light that will render this book anything but definitive. Along the way, and crucial to his aim, is the explosion of some enduring and, one assumes, deliberately perpetuated myths about the man.

Warhol shooting Lonesome Cowboys, 1968

A key part of this is the puncturing of the stories about Warhol’s sex life, or lack of it. If he was happy enough, it seems, to be considered “sexless” – or at least he “preferred to be seen with Edie Sedgwick on his arm as his ‘girlfriend’ … than with the men he invited to share his home and bed” – Gopnik demonstrates that in fact Warhol was not merely “never in full-blown denial of his sexuality” but quite happily homosexually active. As to that contentedness to appear borderline asexual, Gopnik notes, that could be situational as much as anything. Warhol has a subplot that’s a kind of exegesis of a whole country’s slow opening up to coming out, from illicit liaisons in the Grand Central YMCA (one of this book’s innumerable lurid, alluring throwaways notes the club’s approving mention in a New York travel guide named Gaedicker’s Sodom-on-Hudson), to the 1980s when AIDS instituted a whole new kind of closetedness; “There was no way to be gay in post-war America that didn’t involve self-consciously playing a role”, Gopnik notes, which sounds very Andy.

Interview cover stars Isabelle Adjani and Bianca Jagger

From filling department store windows with artwork that looked like set dressing to collapsing the distinctions between commercial and “real” art, advertising and art, mass production and individuation, the sublime and the vulgar (famous beauties in crude poster-paint screenprints), highbrow and lowbrow – as well as subverting the artist-elitist trope by becoming a kind of overgrown “teenybopper” hanging out with the kids at Studio 54, Warhol is the postmodernist’s postmodernist. What we see now as a programmatic and vastly influential philosophy did not, for a long time, win over gallerists, buyers or aficionados; famously, Warhol’s soup cans – the most enduring and instantly recognisable of his works – were first shown in Los Angeles, not in New York: unthinkable in 1962.

Warhol’s shooting, 1968

It took Warhol a long time to overcome the disdain of New York curators and serious commentators. It feels almost as if no sooner had his work received widespread acceptance and acclaim than it was superseded. The theoretical underpinnings of Warhol’s work – a reaction against abstract expressionism – yielded results that ultimately looked the same as the mass-produced stuff that riffed on his own work, meaning, as Gopnik writes, that “the triumph of Pop art in the culture at large wasn’t the sign of success it might seem; it sealed Pop’s doom as serious art.”

Warhol’s all-surface works anticipated the hyper-superficial 1980s, and it’s strange and perhaps instructive that he should fall out of favour at the moment that he somewhat prophesied, if not helped bring about. It is telling that a book of over 900 pages, which spends several chapters on Warhol’s most productive years, can cover his entire final decade in under 100 pages. One reason for this relative brevity is not just that the culture has subsumed and overtaken Warhol’s work, but that Warhol has by now, Gopnik implies, ceased to make anything especially interesting or arresting. Nor, indeed, is the work he does make in the 1980s quite his own: his two major series of this period, including screenprinting on camouflage patterns, are “suggested” to him by his assistants. But while the stories of Interview magazine (founded in 1978) and Warhol’s not unproblematic association with Jean-Michel Basquiat, whom he met in 1982, have been told and retold elsewhere, it’s hard not to feel that this last phase of Warhol’s life gets rather short shrift here. Yet Gopnik concludes by asserting that, despite this decade in the cold, Warhol has eclipsed Picasso as the twentieth century’s most significant artist – a claim that could be designed to generate a dozen more books arguing that particular toss.

Warhol on Love Boat, 1985

This isn’t a serious treatise on Warhol’s actual art – there are many other books dealing with his technique, themes, and the qualities of the work – but it is a serious, comprehensive look at his life, which paradoxically means it can be gossipy and frequently funny, albeit often laughter in the dark. From Brigid Berlin getting so high before being filmed that she was “foaming” at the mouth, to the stated intention of the Factory’s sometime house band the Velvet Underground “‘to upset people, make them feel uncomfortable, make them vomit’”, there’s a cast of more or less appalling, self-absorbed, narcissistic, exploitative scoundrels, monsters, naïfs and freeloaders (plus the occasional good egg). What’s key is that Warhol may have been “the saint of misfits”, but he didn’t consider himself one of them. The Factory might have been full of “this brigade of irregulars”, but its overseer always remained aloof and at a remove.

Chelsea Girls, 1966

In the midst of all this roistering, it feels as though the artist’s mother Julia Warhola is the stabilising, steadfastly un-starstruck centre of his life. She lived with her son for much of his adult life – she arrived in New York in the early 1950s, when he was 24, and died in 1972; Andy would live another 15 years, but the structure of Warhol means she’s present almost throughout – and while Sedgwick, Holly Woodlawn, Paul Morrissey, Basquiat et al come and go, she remains a kind of deadpan presence, perhaps the only person in Andy’s circle to be able at all times to see through him. An account of her famous son’s life from her perspective might be one of the few new biographical approaches untapped at this point. I’d watch that movie.

Warhol’s devotion to his mother is key to one of Gopnik’s other major claims – intriguing even if (or because) it is unverifiable. A childhood episode of scarlet fever is posited as a kind of key to Warhol’s life that would affect his health and his psychology for the rest of his life: a tendency to OCD, persistent body dysmorphia and unusual attachment to a parent are all apparently associated with the illness. Perhaps sensing that this all seems a bit convenient, like the central device in a middling novel, Gopnik doesn’t lean too hard on this formative incident – but it did make me question what we want of a biography. Even if it has a whiff of the cod-psychoanalytical, the notion of a singular key to a person is oddly appealing, while evidently running counter to the work’s chronicling of a human life in all its contradictions and concordances.

Andy Warhol: Shadows, exhibited at the Arts Club of Chicago, 2011

Helpfully, in 1968, two-thirds of the way through his life, Warhol’s life throws up another psychological key moment, when Valerie Solanas enters the scene. Gopnik’s book begins with her shooting of Warhol – noting that the artist was technically dead for a short period – before looping back four decades to his (first) birth in 1928. Maybe this is the pivotal moment when socialising Andy and private Andy diverge. It’s also a gift for a biographer, even if not much fun for its subject: the “reborn” Andy, scarred yet somehow emboldened (he was forced to wear a surgical girdle as a consequence of the attack, but never shied away from having it painted or shown in photographs), was not quite the Warhol who got shot. In one of those remarks that seems, as you read and reread it, to flicker between Wildean quip and something quite profound, Warhol summarised it thus: “‘Before I thought it would be fun to be dead. Now I know it’s fun to be alive.’” C

Warhol by Blake Gopnik is published by Penguin Allen Lane