Step back in time | On Doctor Who fandom, time travel and keeping the faith

Neil D.A. Stewart has a close encounter with a familiar stage prop, and explores the role that a living, breathing fandom has had on his life

Neil D.A. Stewart has a close encounter with a familiar stage prop, and explores the role that a living, breathing fandom has had on his life

“A man is the sum of his memories, you know – a Time Lord even more so.”

It’s spring 1989. I’m 10 years old, going on 11, and I’m pretty happy about that. At some time in the last year or so I have become a fully-fledged fan of Doctor Who, that television show that’s been on forever and to which, after several years of watching with interest but wavering commitment, I have for whatever reason become dedicated. It won’t be back on screen until September, a lifetime away – but fortunately, on this particular day, a schoolfriend has some tremendously exciting news: “There’s a Doctor Who stage play! And it’s coming to Glasgow!” And I think maybe it’s in mid-May 1989, as I’m leaning forward in my stalls seat at the Theatre Royal for The Ultimate Adventure (a universe-spanning epic featuring a television Doctor, Jon Pertwee; arch-nemeses the Daleks and Cybermen; a lasers; wire stunts courtesy of “Flying by Foy”; several song-and-dance numbers; and a character known only as Mrs T. whose appearance provokes an reaction from the Scottish audience that entirely baffles me) that I am fully, wholly, irrevocably transformed into a Doctor Who fan. In a sense, this is unfortunate as, down in the south of England, in studios in London and on location in Buckinghamshire and Kent and Dorset, what is being filmed for autumn transmission on BBC One will be – unknown to anyone up to and including the show’s stars – the last regular Doctor Who series for almost two decades.

I am fully, wholly, irrevocably transformed into a Doctor Who fan

Joining a fandom at a time when its central concern is on the brink of going defunct may seem like exceptionally bad timing. But with no show to watch, fans in the early 1990s got creative. They wrote original novels, got involved in making documentaries or straight-to-VHS dramas starring Doctor Who alumni and/or monsters and/or the occasional household-name-to-be), or became television archivists and restorers. They formed clubs, arranged conventions, and produced fanzines – a form now almost entirely forgotten but whose legacy can be seen in today’s prolific fan-made podcasts, YouTube videos and online discussion forums. (I got in on it too, throughout what fans cheerfully term “the wilderness years”, drawing comics, designing (and even once publishing) fanzines, teaching myself to write as I put together proposals for novels I never quite got to the end of drafting.) With no more Doctor Who forthcoming, almost every single person who’d ever worked on the show, before or behind the camera, was interviewed, in publications including the official magazine, which also commissioned painstaking research into how every single second of the television show came into being – investigations which are still, over 60 years since the first show went out, inspiring new investigations yielding new facts.

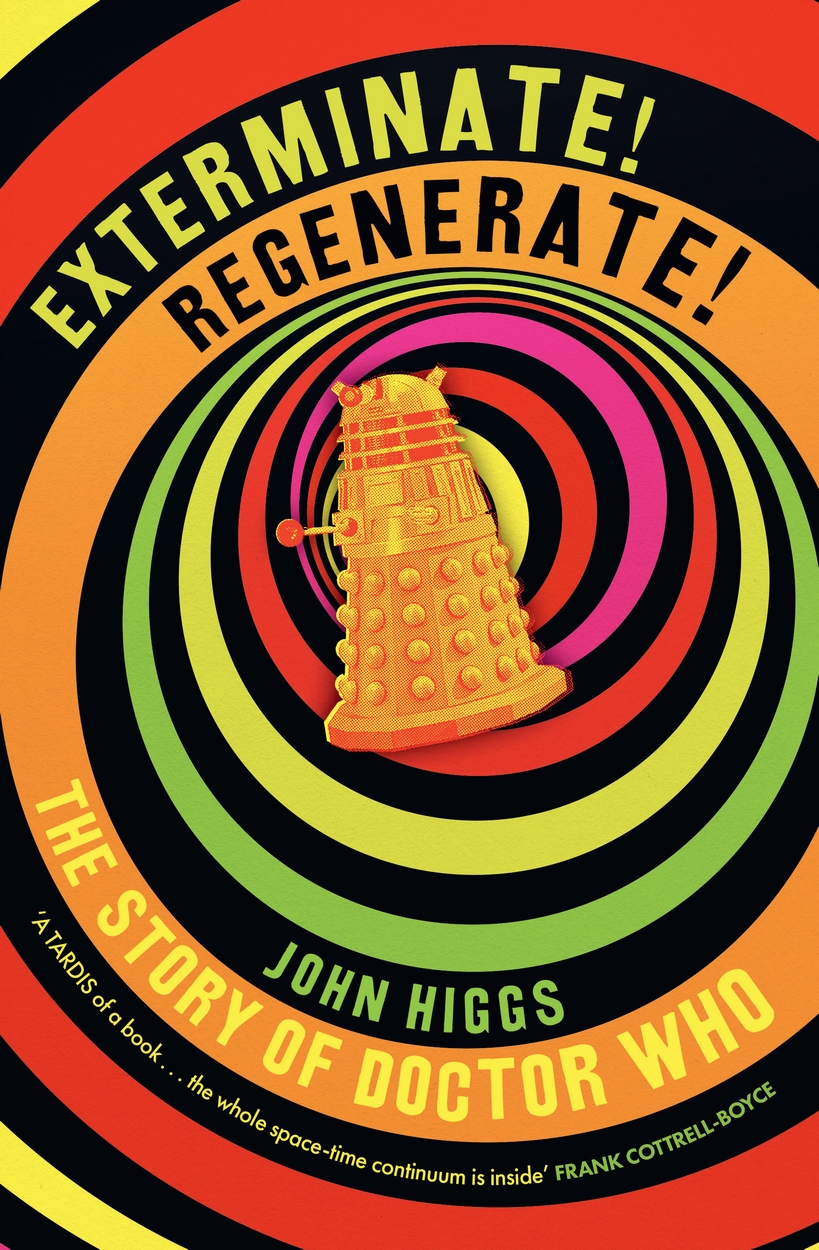

Exterminate! Regenerate!

In his recent book Exterminate Regenerate, cultural historian John Higgs notes that fans’ drive to contribute to the show and the culture around it has made Doctor Who the single most exhaustively chronicled television programme in history. The historian and broadcaster Matthew Sweet, who has presented Doctor Who documentaries and written audio plays, puts it more cutely: if human civilisation vanished today and alien archaeologists arrived tomorrow, they would conclude from the sheer wordcount of published material on Doctor Who that it was one of Earth’s significant religions.

The Doctor (Ncuti Gatwa) discovers that memory is a time machine, in “Empire of Death” (2024)

That quasi-religious element is common to lots of fandoms, of course: think of football supporters dressing their offspring in team colours, fostering the next generation of fans from day one. John Higgs proposes an even more out-there theory: that Doctor Who is tantamount to a living organism, “using” fans’ creative engagement to sustain and propagate itself. In the most recent series, transmitted in 2025, one mindbending sequence saw the Doctor apparently step out of the fiction of the show to meet three stunned Doctor Who fans watching his adventures on TV. The trio were played, naturally, by real-life aficionados, in a scene that literalised the feedback loop in which reality and imagination don’t collide in Doctor Who so much as power one another, on- and off-screen. (It is noteworthy that the episode, “Lux”, was written by showrunner Russell T Davies, the long-term fan whose first Doctor Who credit was as author of one of those ’90s novels.) Whether or not it’s a living organism, Doctor Who is certainly odd. It spills over. It won’t be contained. In its fiction, it’s a show about renewal and transfiguration: sometimes benign, in the genius concept of regeneration that has allowed a programme to regularly recast its central role over a dozen times; sometimes rather less so, as in the numerous episodes in which hapless humans are mutated or possessed or converted or turned into aggressively carnivorous vegetation. So, too, in its making: the twenty-first century iteration of the show, overseen by Davies, has included contributions from numerous figures who contributed to those novels, or had links to fanzines, or wrote for Doctor Who Magazine, or who grew up in the wilderness years – or even in those post-2005 years, for those are old too now – scrutinising episode credits and thought: “Hey, yeah, I could do that.”

Selections from the author’s merchandise collection

It’s 2025. I’m living in London, I am [redacted] years old, and you can imagine how happy I am about that while you’re doing the sums. At the time of writing, for the first time in over two decades, Doctor Who is not currently in production. And on a hot day in mid-July in West Drayton I’m looking, for the first time in 36 years, at the TARDIS set from The Ultimate Adventure – close enough to see the silver tape holding the console’s familiar six-sided shape together. I’m in The Who Shop, which has for several decades been a treasure trove of Doctor Who merchandise and now, in its museum room, of costumes and props from the show. Here are the perishing fibreglass of a “Robots of Death” mask from 1977, some incredibly well preserved garments from the show’s earliest episodes in 1964, and a variety of space guns, masks and models. Outside, the shop sells Doctor Who badges and baseball jackets and little pewter models and cheerfully inaccurate action figures of the 1970s and ’80s and highly accurate action figures of the 2000s and party plates and graphic novels and socks and biographies and replica props and CDs and soundtracks and signed photographs and keyrings and TARDISes in every conceivable shape and size and … you name it, it’s probably here. Did someone say Doctor Who thimbles? You’re in luck. I’ve already picked up the latest issue of the official magazine (which I’ve been collecting since, yes, 1989), and the four recently published adaptations of televised stories – including “Lux”, which makes me wonder how they’re going to handle the scene with the fans. From a box of immaculately preserved fanzines, I pick out an issue of DWB dated November 1989. On the cover is a publicity photograph from “Ghost Light”, the story that was being filmed at pretty much the exact time I was queuing up for the Theatre Royal, aged 11 and suffering from a condition of fandom that might be diagnosable but from which I’ll probably never recover – and gladly so. We all do it, all the time, without even noticing, but if the Doctor is right to say “memory is a time machine”, I’m glad to have the chance to relish the fact that I’m a time traveller, too.

In the theatre, a ghost light is the bulb always left burning overnight in the theatre – a companion for the departed who are still hanging around behind the scenes, intangible but influential, and a glow that lights the way into tomorrow. C

Neil D.A. Stewart is the author of Test Kitchen and The Glasgow Coma Scale