The best books of 2014

From Kim Gordon to women behaving badly – Neil Stewart gives his opinion on the best books of 2014, in the year that the Man Booker spread its wings across the Atlantic, while some of the best reads remained off its short list

From Kim Gordon to women behaving badly – Neil Stewart gives his opinion on the best books of 2014, in the year that the Man Booker spread its wings across the Atlantic, while some of the best reads remained off its short list

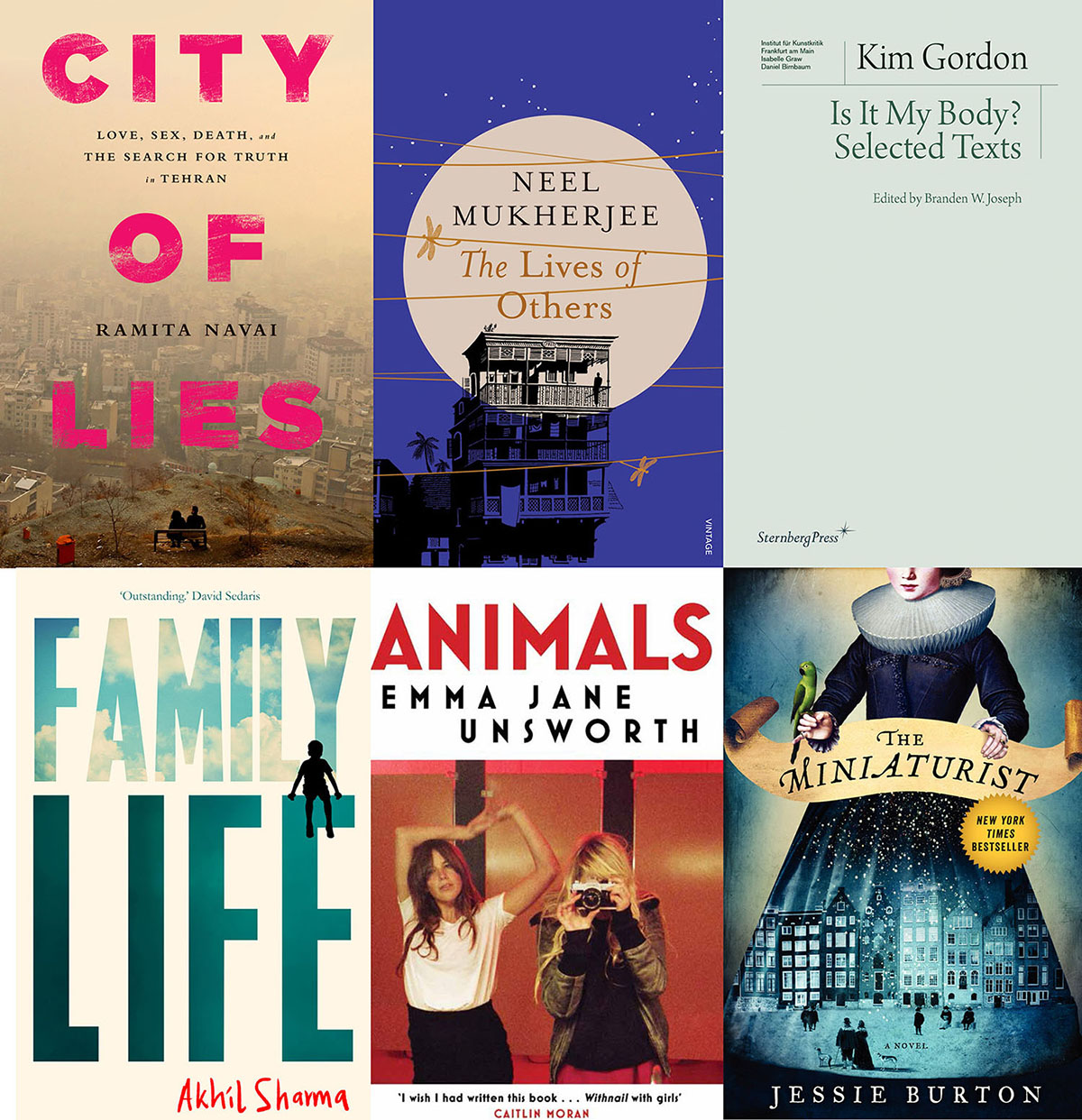

In the year that the Man Booker Prize controversially expanded its eligibility criteria to consider novels by US writers, it was almost inevitable that the prize would go to a writer who would have qualified anyway, as it did to Richard Flanagan for his novel of war and poetry, The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Chatto & Windus). A strong, diverse shortlist also included Neel Mukherjee’s ambitious novel of modern India The Lives of Others (Chatto & Windus) and Ali Smith’s How to be both (Hamish Hamilton), for me the standout of the six contenders. A story about surveillance and observation, craft and reward, masculinity and femininity, the book is in two parts, one contemporary and one set in 15th century Italy, and came with one of those formatting innovations that seems, with hindsight, so obvious it’s extraordinary no-one did it before: in half the print run, the contemporary section comes first, in half, the historical section. Smith says every story is a palimpsest, a fresco through which another story is legible, and that reading is never quite linear and sequential. With How to be both, the temptation on reaching the end is to rebegin and see how the links and associations build between the two tales the other way round.

A comic novel haunted at every turn by death, in which terminal illness, suicidal urges and disintegrating love lives still can’t stop the reader smiling

Puzzlingly absent from even the Booker longlist, Akhil Sharma’s Family Life is a slim book many years in the writing – Sharma apparently ditched draft after lengthy draft until he produced this superbly compressed final version. In barely 200 pages, he does what Karl Ove Knausgaard (whose third volume of My Struggle, Boyhood Island (Harvill Secker; trans. Don Bartlett); its finest so far, came out around the same time) spends thousands of pages unpacking: the happinesses and unhappinesses of an individual family, exquisitely rendered, its precision somehow making the leap to the universal, striking chords in readers, no matter their background. Another inexplicable omission from prize lists – maybe it keeps just missing cut-off dates? – was Miriam Toews’s All My Puny Sorrows (Faber), a comic novel haunted at every turn by death, in which terminal illness, suicidal urges and disintegrating love lives still can’t stop the reader smiling. This was easily, in my opinion, one of the best books of 2014 – certainly one of the most enjoyable reads.

There were new books this year from giants of Scottish, Australian and American letters. A.L. Kennedy published a new collection of her slippery, precise stories, All the Rage (Jonathan Cape); when she zeroes in on the details of, say, a blind date in “This Man”, or the trauma that portends obsession in the tremendous “Knocked”, her eye is forensic and her heart huge. Tim Winton’s long, spiky new novel Eyrie (Picador) swaps the vast, empty Australian outback for cramped urban sprawl and finds beauty and horror in abundance in the city too. Sadly, Lorrie Moore’s Bark (Faber), her first new short story collection in many years, was only a qualified success: while some stories showed her gift for both the comic moment and the affecting remained undimmed, others forfeited quirkiness in favour of broader, clunkier satire.

Inescapable this year were Jessie Burton’s The Miniaturist (Bloomsbury), for which six figures were paid by the publisher and an unrivalled publicity drive undertaken; Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk (Jonathan Cape), a memoir of bereavement and learning to handle a goshawk; and David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks (Sceptre), preceded by the author’s (evidently not entirely happily) presenting a new short story on Twitter, whose quality left me disinclined to bother with the novel that followed.

In non-fiction, I enjoyed Ramita Navai’s survey of diverse lives and lifestyles in modern Tehran, City of Lies (Weidenfeld & Nicolson); Claudia Roth Pierpont’s survey of Philip Roth’s collected works, Roth Unbound (Jonathan Cape), made even more authoritative by the man himself chiming in to comment on her findings; and a collection of Kim Gordon’s writings on art and music, Is It My Body (Sternberg Press), which serves as support act for the Sonic Youth co-founder’s memoir Girl in a Band (Faber), out in early 2015.

Tan’s stories, which are sharp and funny, are also interested in representing the whole spectrum of her characters’ sexualities; in the central story, “Candy Glass”, an actor falls in love with her own stunt double, but refreshingly, the detail that the double is also a trans woman remains a detail rather than the point of the story

Among the most important debuts of the year were Anneliese Mackintosh’s Any Other Mouth (Freight Books) and Things to Make and Break by May-Lan Tan (CB Editions). Tan’s stories, which are sharp and funny, are also interested in representing the whole spectrum of her characters’ sexualities; in the central story, “Candy Glass”, an actor falls in love with her own stunt double, but refreshingly, the detail that the double is also a trans woman remains a detail rather than the point of the story. Mackintosh, too, doesn’t let her stories be limited by any “gay writing” tag, or indeed by any easy categorisation: part memoir, part essay series, part interlinked short story collection, she prefaces Any Other Mouth with three lines, a story in themselves: “1. 68% happened. 2. 32% did not happen. 3. I will never tell.” By turns funny, affecting, heartening and strange, this is a hugely impressive first book.

John Darnielle, the celebrated singer-songwriter behind The Mountain Goats, published a terrific first novel, Wolf in White Van (Granta), executing a highly original premise with skill and care. A debut from Katherine Faw Morris, Young God, (Granta) is, in its slightness and scariness, complement to Darnielle’s book; between them, you get a vision of a shattered and sickly US populated by characters as damaged as the country. For something like light relief, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, which takes its title somewhat arbitrarily from Christian Marclay’s installation The Clock, mixes fiction and memoir in unusual and often indistinguishable ways; it owes something to the Gen X/Gen Y “slacker” novel, but Lerner has a poet’s precision, the writing is very fine, and in its narrator’s increasingly knotty attempts to make sense of the world around him and the decisions life requires of him, it’s often very funny.

Emma Jane Unsworth is perhaps the star of what’s being described, slightly reductively, as a trend of post-Bridget Jones novels of women behaving badly; Animals (Canongate), her second novel, is full of messy nights out, even messier nights in, questionable men and unquestionably bad behaviour. There are good gags on every page, and her central characters are just the kind of girls you’d want to hang around with, against your better judgement. Another compelling woman stands at the centre of Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World (Sceptre): Harriet “Harry” Burden, frustrated artist, employs three very different male accomplices-cum-collaborators to see how a misogynistic New York art scene responds to her work with a man’s name attached to it. And in another fictive exposé, this time of the British art world, Jonathan Gibbs’s Randall (Galley Beggar Press) kills off Damien Hirst in its opening pages and supplants him with the eponymous artist, whose post-Pop art pranks form the armature on which this thoughtful novel is hung. C