Berberian Sound Studio, 2012

Music has long been considered the most affective art: though highly abstract, unable to communicate directly, function as a language, it has a potent effect on the emotions. And, in folk and mystical traditions, certain kinds of musical sounds have long been regarded as transmutative; the chants, incantations, and rhythmic drumming of magical rites act on the imagination to alter the listener’s perceptions. Certain kinds of music, which have both affective and transmutative aspects, can work on the psyche to produce strong sensations and to reify – produce, as if by alchemy, that which does not exist, allowing us to experience places and events, mundane or fantastical, in our heads, in a way that is powerfully felt.

Eraserhead, 1977

Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio is a film which muses on sound’s potential to call the absent into being. In an October 2012 interview with The Quietus, Strickland has described how the idea for the film came about, in part, from listening to Luciano Berio’s experimental composition from 1961, Visage. This piece sees Berio cutting up and rearranging a recording of the voice of his then wife, American soprano, Cathy Berberian, into twenty minutes of glossolalia and howling. It evokes in the listener’s mind a vision of hell, the shrieking of souls in torment, the cackling of demon overseers. Of this work, Strickland says, “It really struck me that in the context of horror, something like this could really work”, going on to note, “In horror, different kinds of music and sound are permissible.”

Berberian Sound Studio depicts a mental disintegration brought about by the effects of these different kinds of music and sound. A sound engineer, Gilderoy, a timid, squeamish native of that most English of places, Dorking, Surrey, who produces the soundtracks of wildlife documentaries and children’s television programmes from a studio in his garden shed, is hired to record the effects for an Italian film, The Equestrian Vortex. On his arrival at the studio, he discovers it is not the film about horse riding he thought it was. Though Berberian Sound Studio’s audience see nothing of The Equestrian Vortex, save its garish red and black opening titles, we soon gather it is one of those lurid, sleazy films that occupies its own distinct subgenre – a giallo. But what begins as a wry comedy of a man out of place and out of his depth, descends into psychical horror. Gilderoy has to record and perform the Foley work for The Equestrian Vortex. Foley work, named after its innovator, Jack Donovan Foley, is the reproduction of film sound effects, in post-production, for adding to the soundtrack to enhance the quality and depth of the audio. It is characterised by innovative means of replicating sounds: one scene in Berberian Sound Studio has Gilderoy squirting water into a hot pan to simulate the noise of sizzling flesh. Sickened by this work on grisly set pieces, and frustrated with the bureaucracy and politics of the studio, Gilderoy breaks down, and his mind and the film unspool. The Equestrian Vortex turns widdershins.

Moore has described conceiving of the record as “the soundtrack from some lost low budget horror movie, rediscovered on an old and faded VHS cassette found mouldering in a deserted house in the depths of the woods”

Berberian Sound Studio is a deeply unnerving film, but, unlike the inferred grotesqueries of The Equestrian Vortex, its terrors are nebulous: sublimated, in the visuals, into meta-filmic trickery and lingering close ups of vegetables that have been hacked-about and pulped, to simulate knives lacerating bodies and skulls thudding to the ground, and which now lie rotting in a bin. Its horrors are only present on its soundtrack, in the sounds made by the Foley artists and the eerie music of the off-screen giallo. Despite the fact that every element of the film’s sound design is meticulously intra-diegetic and has a source within the frame of the film, taken together, they continually point to something happening off screen, outside the frame. This builds an atmosphere of strangeness, of dislocation. We are made to torment ourselves with our darkest imaginings, in an analogue of Gilderoy’s disintegration. Throughout Berberian Sound Studio, sound is substituted for violence, and, though Strickland has stated it is “a meditation on sound as much as it is a meditation on violence”, it is perhaps more a meditation on sound as violence, sound as a radically destabilising and transformative force. In his interview with The Quietus, Strickland discusses how analogue sound devices can have a talismanic, almost alchemical quality; as a sound recordist, Gilderoy has “magical powers” because sound can fire the imagination, summon into being what doesn’t exist.

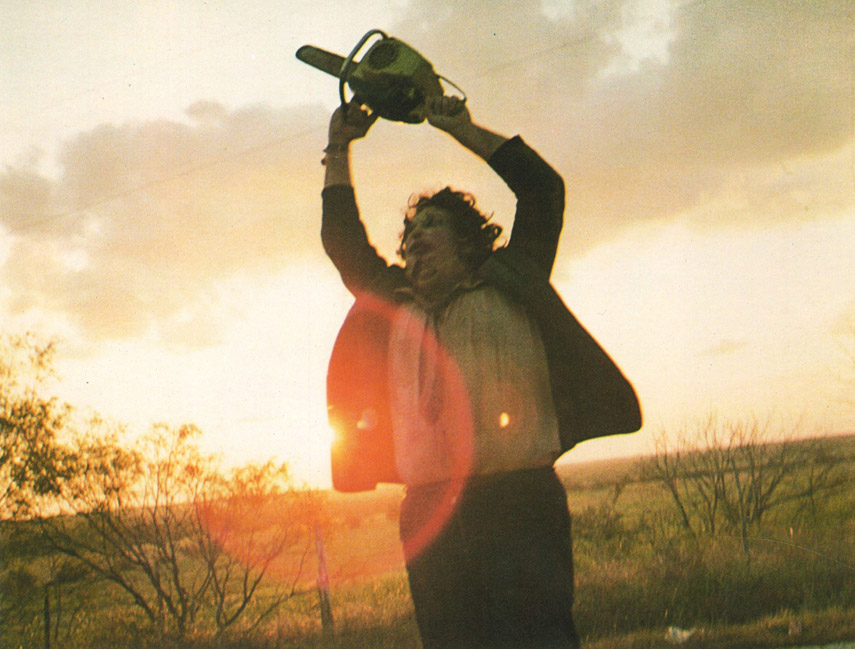

This kind of incantatory power has generally been lost in modern horror cinema soundtracks; now vapid extra-diegetic string and industrial rock cues are overused to generate affect through bombast. But a slew of recent ambient drone artists, who craft what could be termed “horror music”, do channel this strange potency. These horror music artists take influence from classic horror soundtracks – in particular, the giallo work of Goblin and Ennio Morricone, the excoriating industrial noise of David Lynch’s and Alan Splet’s Eraserhead sound design, and the sinister gongs, cymbals, and metallic whines of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre soundtrack – and also horrifying works of the avant garde – such as Berio’s Visage, the stabbing glissandos of Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima, Charlemagne Palestine’s eerie moans, and Phill Niblock’s smothering drones. The best of these horror music records have a potent effect on the imagination, conjuring the films they gesture at. I listened to some of the most evocative recent works in this subgenre and allowed their black atmospheres to work on my imagination.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

• The 2009 album, Black Goat of the Woods, by Black Mountain Transmitter, a project of Northern Irish musician and artist J.R. Moore, alludes, with its title, to H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic-horror entity Shub-Niggurath, but has a distinctly British feel; although it bears the influence of giallo soundtrack work, especially in its opening and closing synth themes, its approach to noise is closer in tenor to a darker, amped-up BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Moore has described conceiving of the record as “the soundtrack from some lost low budget horror movie, rediscovered on an old and faded VHS cassette found mouldering in a deserted house in the depths of the woods”, and the music does recall a sleazy, early 80s video nasty with a supernatural horror theme: a film drenched in lurid cornsyrup, with laughably unconvincing yet somehow deeply repellent special effects. A group of Northern Irish teenagers go, as teenagers are wont to do in these scenarios, to a cabin deep in the woods, to debauch themselves a little, to perform a black rite by the fitful light of a log fire. And of course they awake an ancient evil. One by one they’re taken, though we never see by what, the crew having been saving the effects budget for the grisly finale, when the last surviving girl, having taken shelter in a pitchy burrow, hears a whimper in the darkness, strikes a flame from her cigarette lighter, and sees festoons of tallow and amaranth guts swagging the walls, and follows the moans to find the others, bound by thick roots, still alive, but with bellies slashed, and things growing inside them…

• In Bocca Al Lupo, a 2008 record by Xela, a now defunct project of British electronic musician, John Twells, fuses allusions to the film scores of Goblin and Fabio Frizzi with noise and doom elements to terrifying effect. Field recordings of tolling bells are slowly buried under abrasive electronics. The piece ends in strident noise, half-heard chanting, loose drumming, and, finally fades out on the yowls of the damned. The film it evokes is slow, brooding, and builds to a violent climax. A New-York-based architect and her husband, a poet and painter, visit the home of a long-dead esoterist, a Crowley-type figure, while on holiday in Italy. There she faints and has a vision of a dire ceremony. Her husband’s opinion is that it is a figment brought on by heatstroke, and she allows herself to be reassured by this. When, on returning to the States, she discovers she’s fallen pregnant during the vacation, she doesn’t see it as ominous. But things turn strange and, finally, bloody…

The Haxan Cloak

• The self-titled debut, from 2011, of The Haxan Cloak, the recording project of British sound artist Bobby Krlic, is a work of groaning bass, mournful cello, ragged string drones, the clangour of broken machinery, ritualistic drum tattoos, processed cymbals, and the shrieks and moans of choirs of the damned. It is suggestive of black magic and persecution, torture and torment. In the film’s last scene, a coven, harried by inquisitors, conduct their direst rite, an evocation. Their chanted summons gives way to string glissandos, which, in turn, fade to the faint whine of a rent appearing in the fabric of things.

• William Fowler Collins composes attenuated black metal. On his most recent record, Tenebroso (2012), waves of guitar distortion and frenetic, discordant noise textures give way to forceful but minimal piano figures, and the shrieks of white noise, distant bowed cymbals, and the dread howls of the restless dead are layered like geological strata. Fowler Collins currently lives in New Mexico, and this music evokes mesa and buttes, scrub and desert, the searing heat of a pitiless sun, and a movie in which some city folks’ SUV breaks down on a road to nowhere, near a former nuclear test site, and in the midst of the hunting grounds of some dread beast, some mutant thing.

• Deaf Center’s 2012 release, Owl Splinters, is an album of delicate piano figures and affecting cello lines, at times buried by bass drones that swell to brutal peaks: delirious nocturnes, freighted with menace. The band is Norwegians Erik Skodvin and Otto Totland, and their compositions evoke the eldritch glimmer of the Northern Lights and spruce forests where weird things prowl in the gloom beneath thickly twined branches: trolls, elves, witches, huldra, werewolves, wights, and wraiths. They are suggestive of subtle, eldritch horrors. In an isolated rural community in the north of Norway, a teenaged girl, an outcast, avoided because she is simple, falls pregnant after being raped by some of the village boys. Terrified of the pangs of childbirth, she visits a crone who lives in the forest to beg for help. The old witch instructs her to take the caul of a foal, stretch it between four sticks, and creep through it naked, at midnight, but cautions her that, should her child be female, that daughter will be born a maras, a werewolf. The girl pays this warning no heed, carries out the rite anyway…

• KTL is guitarist Stephen O’Malley and electronic musician Peter Rehberg. Their most recent collaboration V, released in 2012, incorporates a range of influences, including doom, drone, harsh noise dissonance, and the meditative melancholia of sacred minimalism. The first four tracks of the album, moving from sustained metallic tones, through sub-bass rumbles, to saturnine strings and plangent brass, are suggestive of cosmic horror, of things from out of the void, indifferent to human life, pitiless, implacable. It evokes a film in which a journalist investigating a sinister sect infiltrates a number of their weird rituals in worship of hostile alien entities: in a large cavern under the streets of Paris’s 16th arrondissement, a disused warehouse in Silvertown in London’s East End, an aircraft hangar in Wyoming, a paddle-steamer run aground on a sandbank in the Congo river, an Antarctic research base… And the final track suggests a harrowing coda: it’s a monologue, in French, delivered in accents both harrowed and demonic, and backed by wintry electronics by Rehberg and O’Malley; the film’s protagonist, dire warnings unheeded, languishes in an asylum, sanity decayed.

Lovecraft famously wrote that “the one test of the really weird is simply this – whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim”. And it is more effective to insinuate than present directly (Lovecraft’s prose, with its flailing descriptions of “pseudofeet” and “shapeless congeries of protoplasmic bubbles”, and its adjectival pile-ups, could, slightly counter-intuitively, be thought to constitute a claim that representation is in fact impossible, and that insinuation is all that is open to us — pointing always, as it does with its peculiar stylistic tics, to the fact that language is a wreck, that words are insufficient to express the nature of things, no matter how many you lard on). And, as Lovecraft intimates, hearing might be, of the senses, the one most able to evoke subtle terrors. C

Timothy Jarvis was born in 1978. He is a writer and critic with an interest in the antic and the weird. If you enjoy any of this music, please support the artists mentioned in this story by buying their work.