It was early August 1994 and I was sitting in my cell in the monastery by the window. The cells were small, yet comfortable – not as one would imagine monasteries at all. My home was a modern attic built on top of the neo-baroque original structure in the middle of Budapest, next to the church’s spire. I immersed myself in the bells ringing, when they did. I looked up at the cross and contemplated how my time as a candidate was going to end soon, and how we’d all be moving to the country, to a much more secluded monastery for our time as novitiates. There we would be given our habits and new names. Even though I had been preparing for that moment for about two years (and in 1994 I was hardly 18 yet), it felt like the great divide of my life: before and after. I was getting closer to the big flashing EXIT sign in my head, an exit from reality.

I was getting closer to the big flashing EXIT sign in my head, an exit from reality

The monastery was primarily the home of priests and elderly friars. Most of them had endured the same horrible four decades of life as anyone else who hadn’t emigrated, while vehemently disagreeing with Hungary’s politics. Come the 1990s, they were allowed to move back to the orders they had been exiled from in the 1950s, and could find what they thought was peace. For some of them it was. In others, their accumulated frustration turned into hatred and bitterness, which then found an outlet in politics, homophobia, conspiracy theories or simply being mean to others. But who are we to judge? It is unlikely anyone from my generation is going to have to go through half a lifetime under such circumstances, and the oldest monks told stories of unimaginable times.

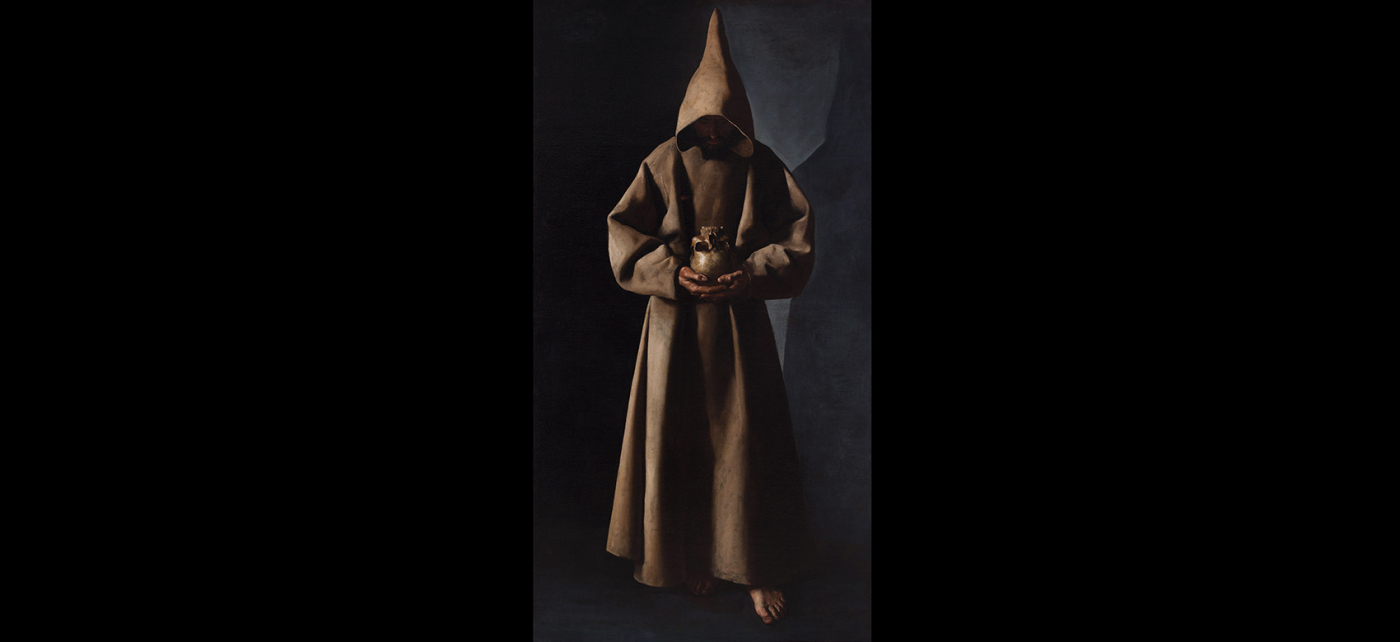

Kristof in the early 1990s

It was an odd, but somehow harmonious pairing: the youngest and the oldest, the generation of the new era, and the generation of persecution. We young ones stuck together, and got along quite well because of our age and enthusiasm. Occasionally we would creep down to the cellar late into the summer evening and drink a couple of glasses of mass wine, or sneak out to the nearby McDonald’s, still a new thing in Budapest in 1994: the first branch had opened six years before and still had a kind of romanticism about it: the ice cream there seemed to taste better than anyone else’s, the burgers were cooler, the fries crispier. I could not make myself eat there now, but back then, it represented almost what being freely able to become a monk did. It was a different, fresher freedom – that of the West – and it smelled of oil and grilled meat of questionable origin.

Other than this, we were all dedicated, in body and mind, to the monastery. It represented a kind of bucolic idyll, which I probably haven’t experienced since. An idyll equates to perfection, making you believe that the plan you’ve mapped out is the right one.

when I was nine, I nearly drowned in a swimming pool, and until I joined the monastery I was petrified to go into deep water

Most mothers, when their sons tell them they are gay say, “I should have known, there were signs…”, and God, do I feel like the mother of a gay son looking back. I remember an evening gathering with the other candidates and the leader of the province. He was reading a part from one of the gospels where Jesus gets into a boat with his disciples and they look at the crowd waving and cheering from the shore. Once he was done reading, we went in a circle and each of us described what he made of the story. Every single guy spoke talk about feeling privileged to be in the boat with Jesus and to be his disciple. But me, wanting to be different for who knows what reason, said how happy I felt to be waving from the shore and seeing Jesus, knowing he is there. I’d stayed on the shore. Nowhere near the boat. I was a notoriously crap swimmer, too, though funnily enough, the little swimming I know now, I learnt from the friars. No symbolism there; when I was nine, I nearly drowned in a swimming pool, and until I joined the monastery I was petrified to go into deep water. That’s when a couple of the friars took me to a pool and stood beside me until I got through the first few lengths.

The monastery, with its smell of bedsheets overdue for changing, had an alluring make-believe peace. It framed our lives with its early morning masses, five times of prayer daily, chores to be done regularly. Everything was laid out for you: there was no need to think, no need to plan. An idyll. All you had to ponder was what your name in the order would be, and if you wanted to go on to be a priest or a friar, wanted to teach or not. I liked living there. There were no existential questions and no sexuality. Just peace and order.

All of this was appealing to a neurotic boy in his late teens. I was swimming towards what I believed was my calling, comforted by what I thought to be sacrifice as a pure, dedicated child of God. And this was how I felt in my cell on that early August night, looking at the spire and the cross, waiting for the letter detailing my next move.

The next day, we all assembled in the room of the chief of the province. A letter was handed to each of us. We were all glowing and grinning, opening them up one by one. What an amazing rush of adrenaline. What an amazing rush, until I got to the words: “We believe you are not yet mature enough to continue in our order. Therefore, we recommend you go to university and after obtaining your degree come back and join us, if you still feel this is your calling.”

A few years before this happened my father had quite an intense nervous breakdown. I’d had no experience of mental illness, and his breakdown seemed like an act, a nuisance and a hurdle to what I wanted to do. Now, this sudden change to what I’d assumed was my destiny broke me into tiny pieces. For the first few days, the monks had to administer tranquilisers (a sign that they had made the right decision, perhaps). Even when I came off them, I was a zombie, helpless, unable to communicate or face the world.

When they allowed me back in the monastery that October, “to help with the elderly fathers”, it felt like the conversation that follows an awkward one-night stand – short and stilted. There were two of us who returned at the same time. I lasted until the following February, when I moved back home. The other guy lasted until September. That’s when they found him hanging in his cell, with its window and view looking straight up to the spire. C

Kristof Hajos-Devenyi is the founder of The Unbending Trees

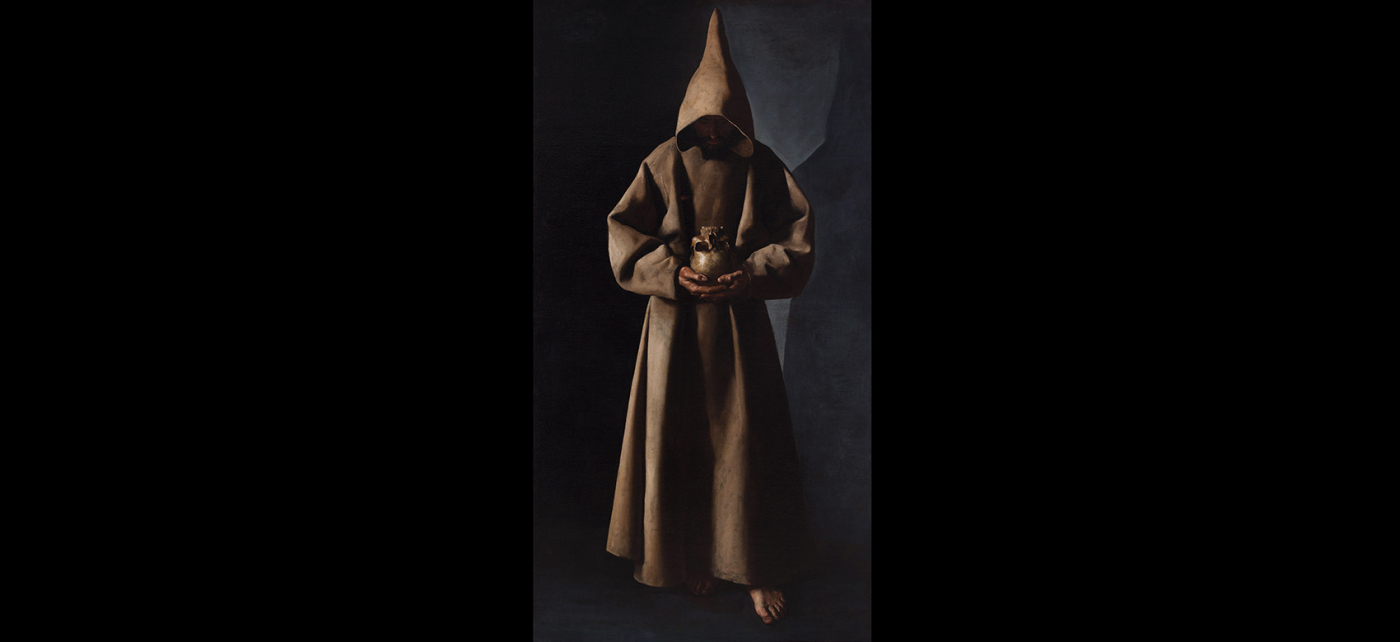

Picture (top): Francis of Assisi by Francisco de Zurbarán