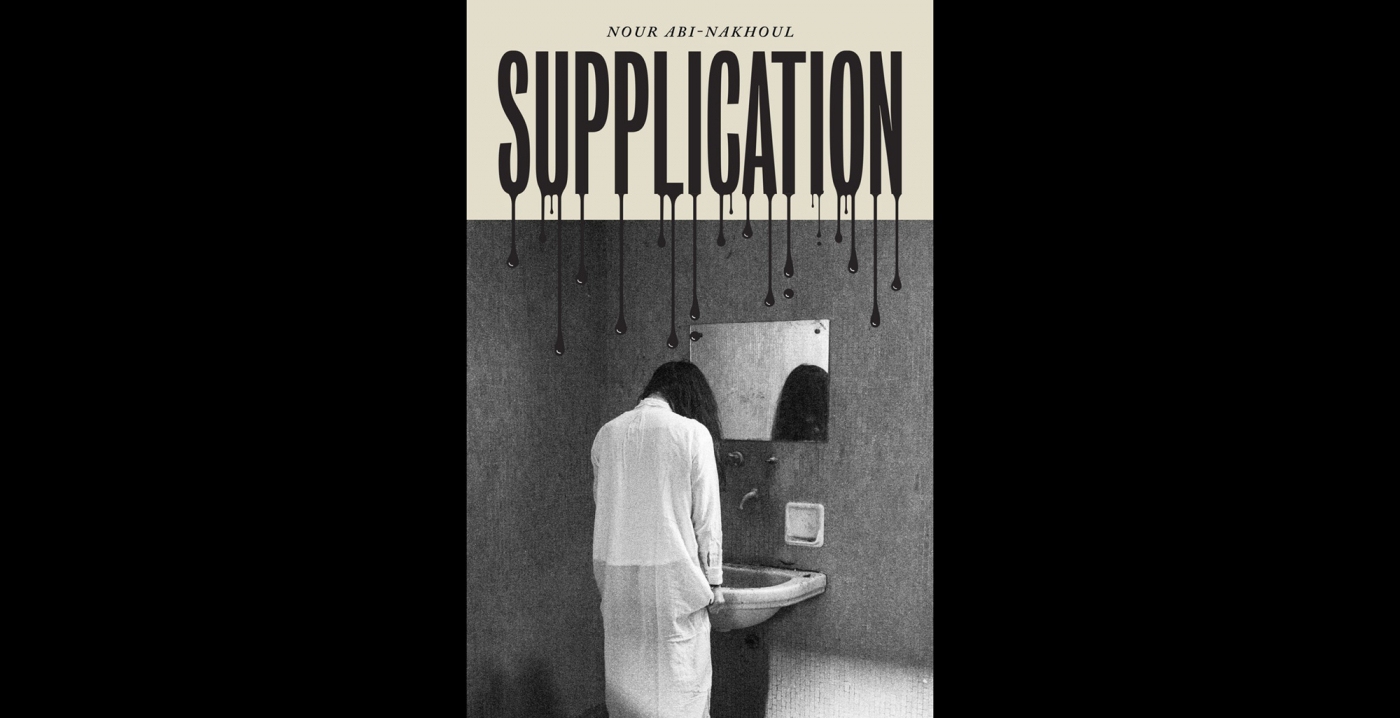

Review: Supplication by Nour Abi-Nakhoul

A debut novel tackles twenty-first century alienation in eerie set-pieces and through the tropes of horror. Neil D.A. Stewart surrenders to a haunting novel of weird ideas

A debut novel tackles twenty-first century alienation in eerie set-pieces and through the tropes of horror. Neil D.A. Stewart surrenders to a haunting novel of weird ideas

Our nameless, voiceless narrator comes around in a dingy, ill-lit basement and slowly becomes aware she’s not alone: standing over her is a man she doesn’t recognise, and he’s holding a knife. She doesn’t know what he is going to do, but she knows it won’t be good – and maybe the only way to cope, to prepare herself for the moment he will sink the knife into her body, is to welcome the violence, accept it, invite it. Some books would get their whole narrative out of this; debut novelist Nour Abi-Nakhoul gives us the violent act barely a dozen pages into Supplication, her narrator’s deadpan response a prelude to the unsummarisable nightmare that ensues: “It was the first time I died.”

The novel unfolds as a series of oblique set pieces taking place in environments that have the shaggy, unfinished atmosphere of rudimentary stage sets: the narrator explores the murderer’s house, a pub, a clapboard house, a medical institute. Intriguingly ambiguous, too, are the motivations of the more or less sinister characters she encounters in these places. In the pub, she meets a couple who invite her home where they offer her snorts of an orange powder, the limit of their hospitality; she hallucinates, while the couple observe her more or less disinterestedly, a set piece that feels clammy and pregnant with all kinds of possibilities no less unpleasant for the fact they don’t develop in anything like the way the reader might expect. Instead, the narrator is undergoing a mysterious interior change that is, if anything, more alarming.

I’ll contentedly consume any quantity of bodily grotesquerie, haunted houses and monstrous otherings

She’s not alone in feeling a kind of disembodiment, or perhaps overly embodied. Supplication’s characters seldom seem quite in charge of their bodies (“The attendant picked his head up off the floor and pointed it toward me”), which means that in the rare moments of self-determination, as when the narrator “bound[s] out of the house … taking hold of the door and throwing it open”, the directness of the verbs – the concreteness of the description – is almost shocking. Not unrelatedly, she soon notes: “When I felt the cool air on my skin and the wood of the front porch beneath my feet, I didn’t think, there were no thoughts in my mind”. For the most part, this is a novel in which bodies are meat machines that resist control, and in which connection and communication are next to impossible – prevented by a kind of anomie and alienation that operates even on the atomic level. The narrator is increasingly aware of a “tiny, unnoticeable distance” that exists even “between the bones and the muscles, the veins and the blood, the pupil and the iris[:] everything was held just ever so slightly apart from everything else; nothing touched. This impassable distance exists every place where two things meet or where a thing meets itself … ensuring that nothing can ever really touch me, that I can never really touch anything else, that there isn’t any touching, any breaching of the boundaries.”

The benchmark is David Lynch, with whose early films Supplication shares a voyeuristic clamminess

Overthinking, then, is paralysing, but Abi-Nakhoul takes this metaphysical twist on the sad-millennial novel further into horror by suggesting that this impassable distance is not in fact empty, but occupied by “an animating force, a thing that desires, that wills, that pushes at every pulsing atom … working tirelessly to keep everything apart, from ever truly touching.” From this dark space emerges the novel’s sticky, nasty moments: impossibly tangled hair spews from faucets, an oily sludge flows through unsettling gaps in the world, and the narrator carries within her a black worm – a perhaps too popular trope in literary horror at the moment. (On occasion, I felt Supplication’s vocabulary undercut the intended effect, imprecise and oddly cheerful words such as “splodge” and “plasticky” a mismatch for its nastiest moments.)

I’ll contentedly consume any quantity of bodily grotesquerie, haunted houses and monstrous otherings, and Supplication delivers on all these: I loved the character caught in a time loop that the narrator cannot stand to look at and, by blinking, seems to make recur, and the extraordinary notion of drinking gasoline as a way to communicate with a kind of collective unconscious of our fossilised common ancestry unwillingly disturbed in its rest by the oil industry’s excavations. Nonetheless, a novel like this stands or falls on its ability to balance the hallucinatory and freeform with a sense of internal logic and consistency. (The benchmark is David Lynch, with whose early films Supplication shares a voyeuristic clamminess.) Ambiguity works best when there is a sense that its author knows exactly what is going on, even if they withhold the key to understanding. Fortunately, there’s never a sense of this novel getting out of Abi-Nakhoul’s control; and so, reassured that this all means something, the reader is free to theorise enjoyably. “I became myself,” the narrator recounts in that early, eerie basement scene, as her tormentor lunges, “so I could become something else.” What happens next? Where does the narrator “really” go, and where does she return to when she rebuilds, in the last few pages of this transfixing and unnerving novel, a version of what has gone before? I have my own ideas, in which a knife is not a knife, a death is not a death, and there are all too real ways in which a body may no longer be one’s own. C

Supplication by Nour Abi-Nakhoul is published by Influx Press.

Neil D.A. Stewart is the author of Test Kitchen (Corsair).