When I was introduced to Leigh Bowery by Lorcan O’Neill, he was one of the dealers at The Anthony d’Offay Gallery in Dering Street. Lorcan had suggested to Anthony that Leigh should perform there, and they agreed. Lorcan mentioned to me that I should meet Leigh because he thought we would get along and that we should consider doing some photographs together. At the time, I was working full-time as Terence Donovan’s assistant and studio manager.

“Lorcan thinks we should do some pictures together. What do you think?”

Lorcan suggested that I attend one of Leigh’s performances, and afterwards he introduced us. We had a brief conversation, during which Leigh said, “Lorcan thinks we should do some pictures together. What do you think?” I agreed, saying I thought it would be a good idea, and so we both decided to arrange our first session.

As a struggling assistant with little money, any shoots I did required calling in favours. This was common practice among assistants, and the industry was always supportive of the relationships you built. I asked Vince McCartney, who owned Holborn Studios – where I had first worked through Terence’s introduction while I was still in the army – if I could do a test shoot on a weekend when the studios were generally quiet. Vince agreed. Labs also supported assistants by offering discounts or free processing. I went to Lancaster Colour, a lab around the corner that Terence used for transparency film because they were the best in London at the time for neutral colour processing.

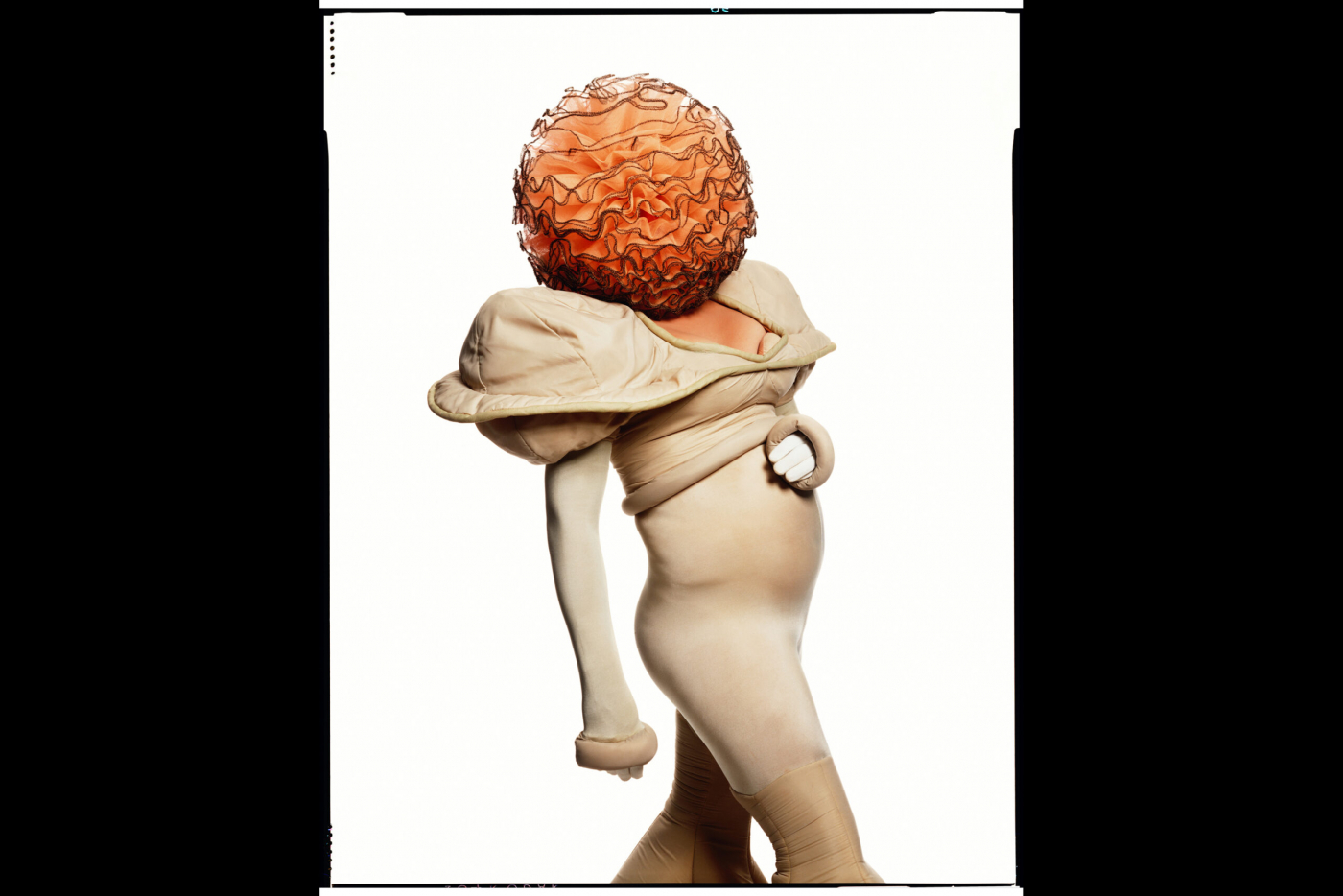

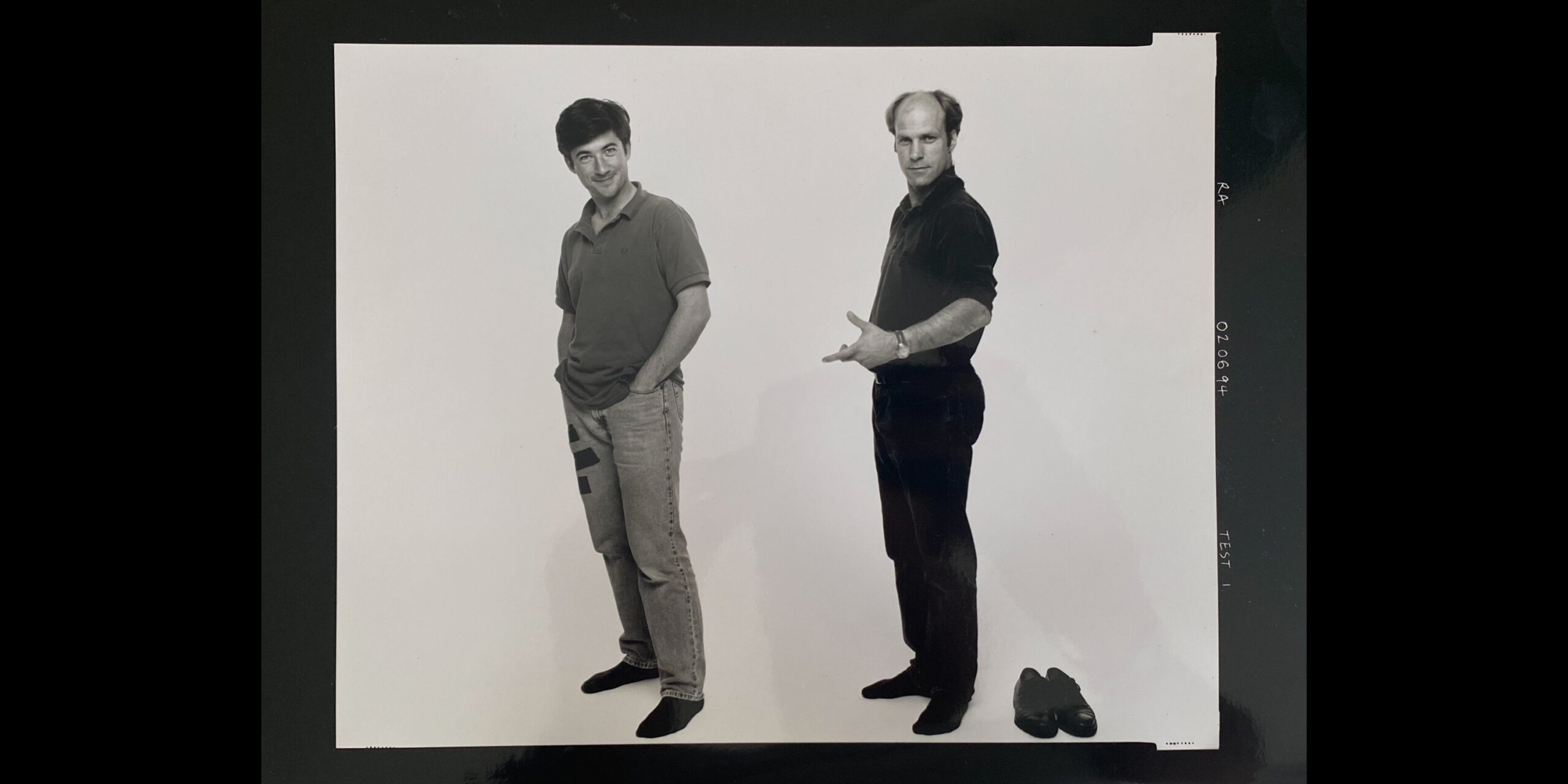

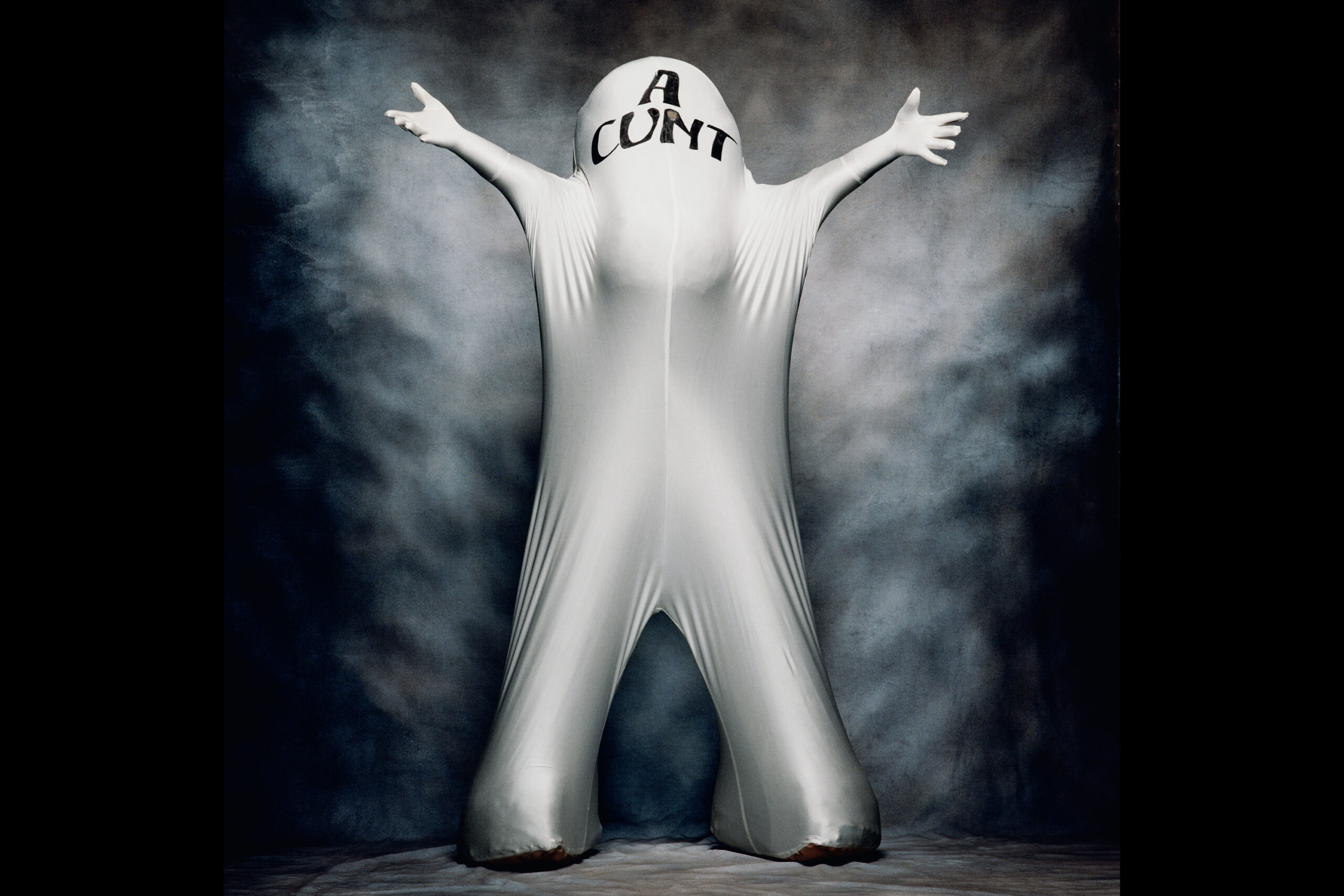

Leigh Bowery by Fergus Greer

Gradually, I pulled together a studio setup, rented cameras, borrowed lights, and bought film. Leigh and I had our first session together (the image on Tate Modern’s site promoting the 2025 show came from that first shoot). I was still clumsy with my craft, and much of the lighting and style reflected Terence’s work, so my early shoots were heavily influenced by him.

As time went on and I later worked for Avedon, you can see his influence appear in my work, especially in the use of large format film and lighting. This period was crucial in my transition from assistant to a photographer, helping me find my own creative voice in how I approached subjects and shoots. Did I approach the shoots from a fashion perspective? Like much of Avedon’s work, I think the approach I took to fashion and portraits was the same in terms of technique and process. I didn’t label it. I simply focused on what was in front of me and how I could visualise it to the maximum effect, based on how I felt about it from a visual and visceral perspective.

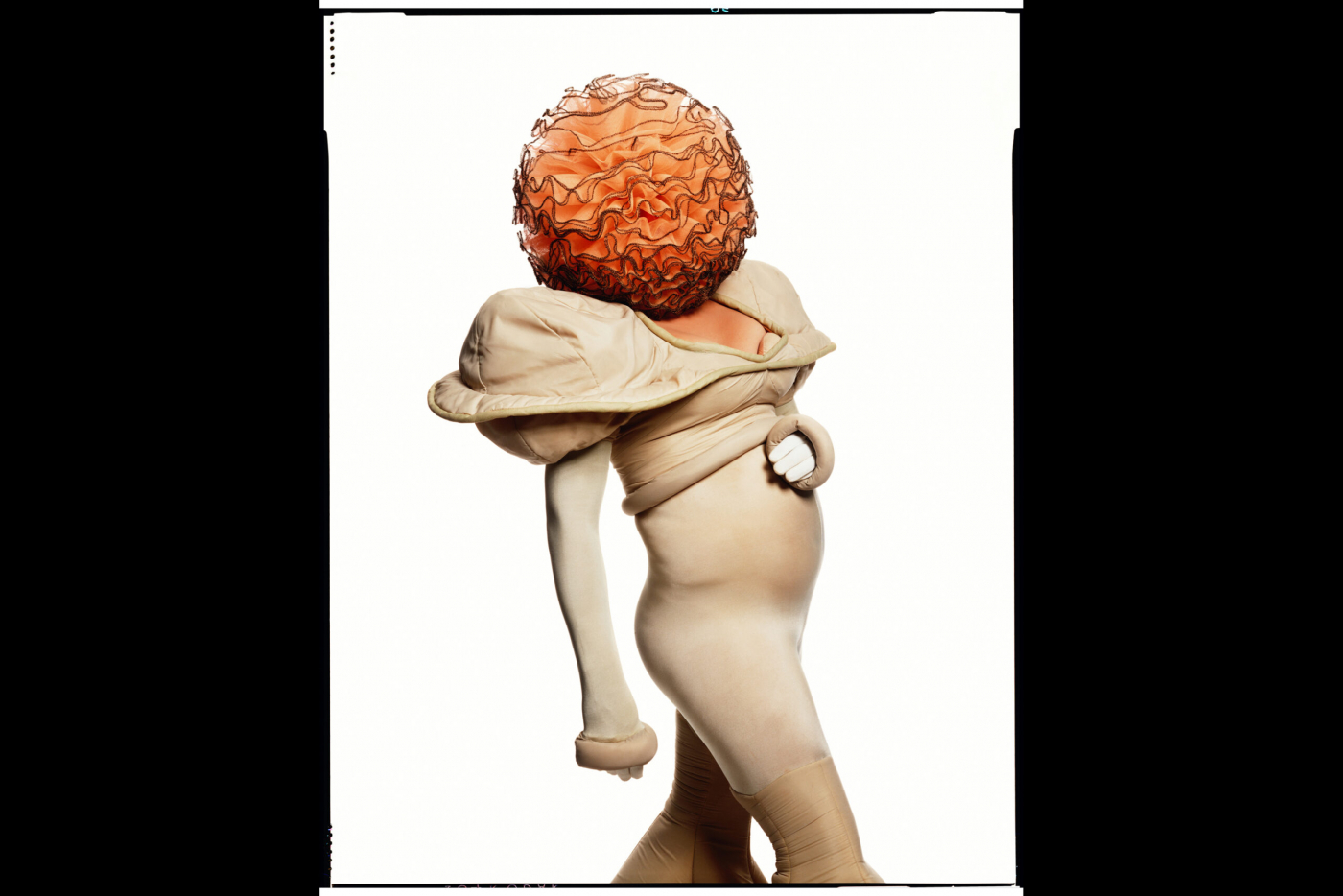

Fergus Greer with Quinton Wright – from a contact sheet by Avedon

I never became a mainstream fashion photographer. Oddly enough, when I left Terence, he told me I would become a portrait photographer, not a fashion photographer. It took me a while to realise he was right and to understand why – the desire to find the truth about the subject as to who they are and the life they have travelled and how that has formed them. It wasn’t my choice; it was the path I was led down by photo editors and art directors who responded to my work and commissioned me. Leigh brought himself, Nicola, and his looks – that was his art and creative genius. I brought my emotional reaction to record it through the medium of photography.

Having seen many great photographers work while at Holborn Studios, and observing how they lit and worked, it became second nature to understand the application of the craft. The craft is about quality and setting the stage for the scene.

Leigh Bowery by Fergus Greer

The scene or performance that is captured is a very intimate relationship between the subject and the artist (the photographer), with varying levels of collaboration depending on the nature of the shoot. Fashion often involves more people – stylists, hair and makeup artists, fashion editors, etc. – while portraiture is often more stripped back, enabling an intense experience between the subject and photographer to build a relationship and elicit emotional and physical responses, which are then caught on film in that moment. The craft is essential to enable the latter situation to be the focus and to capture a moment. Professional rigor and discipline are required to ensure the craft is exacting, to produce a well-executed, quality image that projects into the viewer, allowing them to have an experience.

Like painting, some images can be more conceptual, like realistic painting, while others evoke metaphysical responses, akin to abstract painting. Look at Annie Leibovitz’s work, much of which is conceptually driven and easily readable by the viewer, as opposed to Avedon, whose portraiture often captures the human essence of the subject.

Images are composed of three elements: the craft (medium), the composition within the frame (negative and positive space), and the subject. Certainly, what I learned from both Terence and Avedon was the importance of the detail and rigor put into the craft, and the importance of consistently exacting standards in preparing for the shoot, as well as the composition and creative style of the scene, whether on location or in the studio. The experience and creative thinking needed to enable the third part, arguably the most important – to facilitate an emotional, intimate relationship with the subject, capturing that fleeting moment when you press the shutter and expose the film, creating an image composed of all three elements.

At some point, while still in conversation, he would signal to his assistants that the time was near

To give a clearer, more clinical example: When working for Avedon as his assistant, Dick had very specific, rigorous requirements for the equipment, studio, lighting, and film. Depending on the particular approach or setup he wanted, we might spend two days preparing the set or studio. This would include the detailed placement of lights, the types of lights, and all associated equipment. Once the lights and readings were accurate, we would test the film and cameras to ensure everything was correct. A small black “X” made of gaffer tape would be placed on the usually white floor, marking the specific area where all aspects of the set were centred. When the subject arrived, often only for about 30 minutes or a little more, Dick would spend most of that time in the lounge area of the studio, talking with them. It might have been Dennis Potter, Tilda Swinton, Isaiah Berlin or Stephen Spender – he had heavily researched them beforehand so that he could use this time to build rapport. At some point, while still in conversation, he would signal to his assistants that the time was near, and we would position ourselves for our tasks. While still talking, Dick would then guide the subject to the spot, using the relationship to elicit different expressions, emotions, and movements, while maintaining eye contact. He would use a cable release to take images.

Leigh Bowery by Fergus Greer

Terence was the same – whether working on the ‘Addicted to Love’ video with Robert Palmer, or with Princess Diana and King Charles, the continued rapport with the subject was always key to capturing and maintaining a relationship while photographing, to capture an image that was alive and projected basic yet complex human emotions to the viewer.

Bear in mind that 70% of human communication is non-verbal. The process I learned from my mentors as their apprentice, as was the case with artists during the Renaissance and before, informs my work. I learnt more technique and craft from Terence, while from Dick it was his approach to subjects. Most of his portraits, including his In the American West series, are powerful beyond belief, just to “see people”. It represents the great human predicament – people want to be seen, but they don’t want to be seen. That is evident in the images I created with Leigh.

Some of Leigh’s looks didn’t allow for much facial expression, which meant that the physical aspect was at times more emphasized. When I photographed Ray Charles, for example, saying “smile at the camera” doesn’t work! That’s a metaphor for trying to understand more of the complexities of human relationships and the importance of rapport in capturing a strong photographic image. It’s about the relationship with the subject and enabling them, in whatever way, to project themselves so they can be captured for that brief moment in time on film. Like the “punctum” moment as Roland Barthes might say, or the insights John Berger outlines in Ways of Seeing, these elements help deconstruct the image for greater understanding.

To me, it’s always about finding the truth in the subject while also not letting the technique become apparent, so as not to distract from the subject. I want the subject to be seen, allowing viewers to continually return to the image and discover new aspects of the subject’s humanity and history.

Perhaps that’s why I then became a psychotherapist. I am still looking for The Truth. C

Fergus Greer

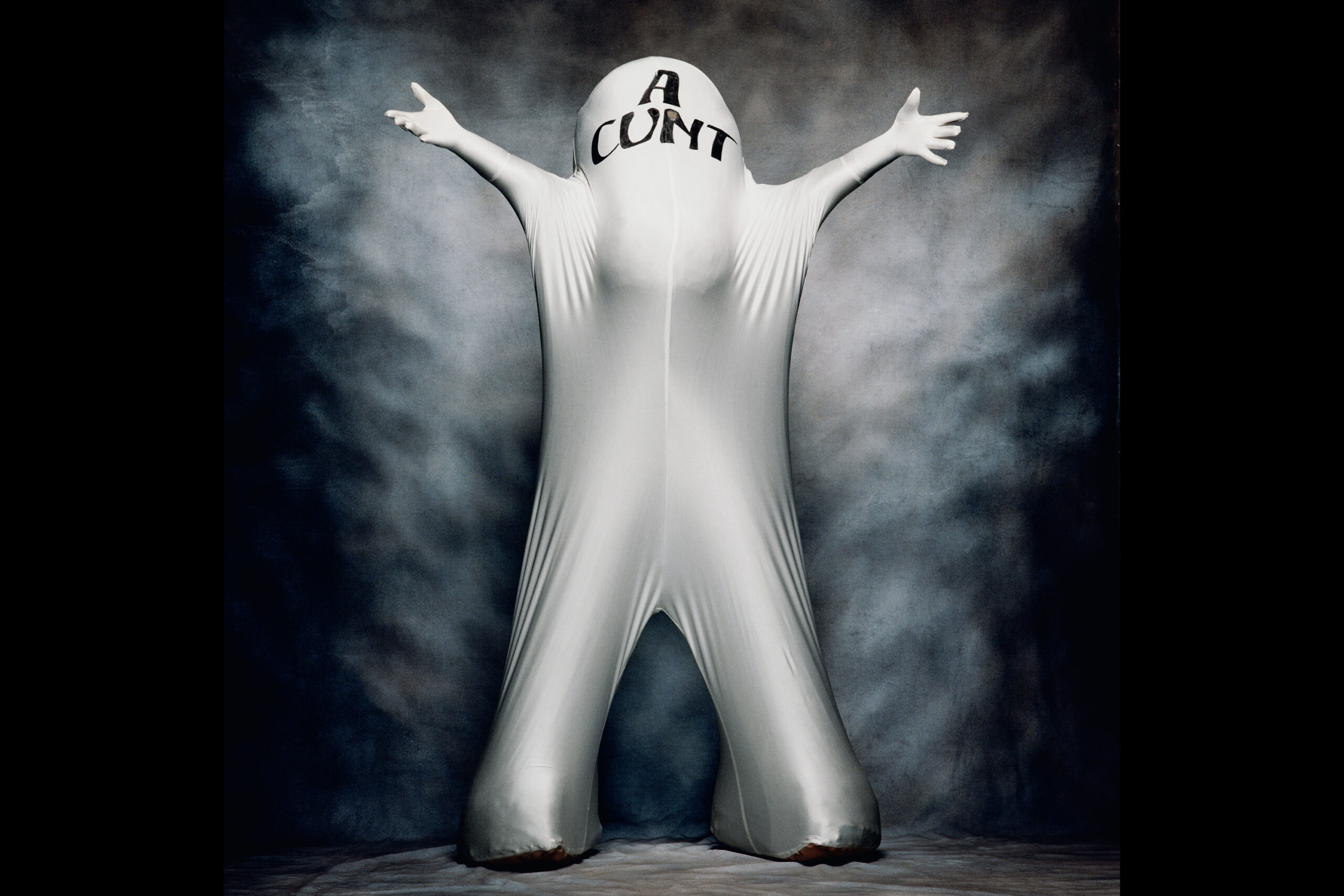

Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London, Fashion and Textile Museum, London (October 4, 2024 — March 9, 2025)

Leigh Bowery! Tate Modern (February 27 — August 31, 2025)