Writing despite and to spite it all | The best books of 2024

Publishing felt particularly under siege in 2024, yet amid its pressures, authors were producing incredible work. Neil D.A. Stewart selects his highlights from a time of darkness

Publishing felt particularly under siege in 2024, yet amid its pressures, authors were producing incredible work. Neil D.A. Stewart selects his highlights from a time of darkness

In 2024, for only the second time since I started compiling these annual roundups for Civilian, I was in the happy position of publishing a novel of my own. The process of working on Test Kitchen, editing it, selling it, editing it some more, and finally seeing it on shelves and in print refreshed my admiration for anyone who brings a book into the world – which is why I also launched the Brunswick East Book Salon, to showcase some of my favourite writers and books in a real-world space. Among them are friends who brought out brilliant books in 2024 (books which, though I recommend them all wholeheartedly, I’ve deemed ineligible for this article, to avoid accusations of log-rolling): Lara Haworth’s Monumenta (Faber), Toby Lloyd’s Fervour (Serpents Tail), Neel Mukherjee’s Choice (Atlantic), Misha Honcharenko’s Trap Unfolds Me Greedily (Sissy Anarchy), Ali Millar’s Ava Anna Ada (White Rabbit) and the latest Scholastic title for younger readers by Civilian’s own M.C. Ross.

This year unscrupulous parties really started trying to lay waste to the creative industries

More so than ever in 2024, it seems to me to take courage – the against-all-odds kind – to publish anything. This year unscrupulous parties really started trying to lay waste to the creative industries, deceitfully insisting that algorithms are as capable of creating valid works of art as human beings, when of course these largely theft-based systems are merely regurgitative, their great appeal to tech folk (and haven’t we had enough of those?) being that they don’t answer back, ask for royalties or go on strike. Even taken on its own terms, so-called machine learning yields, by definition, only echoes and garbles of extant works, gremlin-riddled tenth-generation mishearings produced at indefensible cost. The books that stood out to me in 2024 were those which surprised at every turn, which were at once wildly inventive and yet entirely self-consistent: AI, as the meme might have it, could never. These books come from the greatest resource we have, one which capitalism seeks to colonise and extinguish: the weird and visionary human imagination.

Chief among these triumphs, for me, was Miranda July’s All Fours (Canongate), in which an artist announces her intention to drive across America, from its east coast to its west, but instead gets as far as the next small town along from her home, where she falls instantly in love, books a motel room, and proceeds to wreck her life – or perhaps save it. This is a novel for anyone who’s ever felt wanderlust tempered by the old saw of “wherever you go, there you’ll be”; July’s central character by turns rends your heart with her vulnerability and makes you want to bang your head against a wall with her self-delusion – yet she’ll also give you whiplash with her one-liners and insights. If “a comedy about perimenopause” isn’t an appealing sell, think of it as the freakiest episode Schitt’s Creek never got round to making.

2024’s finest

Eventually, July’s protagonist has to go home to face up to her choices; this felt like a recurring theme in much fiction this year, even if returnees often find there is, in Gertrude Stein’s term, “no there there”. One who finds this out is onetime popstar Lydia, in Rose Ruane’s Birding (Corsair – full disclosure, Ruane and I now share both an agent and an editor), who returns to a vividly crumbling English seaside town, all vandalism and tainted air, to reconnect with her former bandmate and confront a past she has come to believe was exploitative and disempowering. Meanwhile, in another part of town, middle-aged Joyce is trying to wriggle out from under the thumb of her manipulative mother Betty (one of the great Terrible Mothers of recent fiction). Ruane treats her characters with as much affection as ruthlessness, and the journeys these characters undergo are satisfying, spiky and utterly believable.

Following a bad breakup, the narrator of The Plains by Federico Falco (Charco Press, trans. Jennifer Croft) departs city life and returns to take charge of his family’s ramshackle house and land. Here he finds himself drawn to a new form of living, one that follows the seasons, and new, literally homegrown pleasures. I found this deceptively simple novel very moving, especially as the narrator comes to terms with the fact that life seldom offers the great resolutions of grand narrative but offers different kinds of compensations. Another family home becomes a locus of conflict between different tellings of the past in Yael van der Wouten’s The Safekeep (Viking) – the highlight, for me, of a patchy Booker shortlist. Once the story has delivered its big narrative twist, it takes a snakier emotional path that is even more satisfying. The past won’t always lie still, but its irruption into the present can lead not to conflict but to kindness and reconciliation – a notion that feels something of a balm in these times. Similarly, Phoebe, the main character in Wild Geese, the debut by Soula Emannuel (Footnote), is trying to avoid her past by leaving Ireland for a new life in Denmark – except the past, in the form of an ex who turns up unexpectedly, won’t leave her be. Like a number of novels I enjoyed this year, Wild Geese is a contemplative book that unwinds at a careful pace and concludes on a note of hopefulness.

The background noise throughout 2024 was the rumble of war, deliberately kept – in the western media, anyway – at a kind of remove, as if none of our business. Two exceptional books from And Other Stories illuminated the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict, and how the grief and grievances of the past inform the present. In Lublin, Manya Wilkinson follows three young Jewish boys travelling on foot through the Poland of 1907, selling brushes village-to-village, a journey of sixty miles. Their wits, charm, spirit and friendship buoy them up, but as the journey gets longer, the book gets stranger, as Wilkinson breaks form to hint that the boys are heading not to Lublin but towards the twentieth century’s darkest moment. Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance (trans. Sinan Antoon) functions as a sort of oblique sequel: in present-day Tel Aviv, self-proclaimed “liberal Zionist” Ariel wakes up to find that every Palestinian has vanished overnight from the occupied territories. Ariel’s bemused efforts to find out what has happened to his neighbour are set against the response by the political authorities, which turns quickly to paranoia: where are the Palestinians hiding (for hiding they must be)? What are they planning (for this can only be prelude to retaliation)? Read together, these two taut, unnerving novels tell us a great deal about the times we find ourselves in, even if what they seem to hint about the future is less than heartening.

More must reads

Also illuminating is Belén Lopéz Peiró’s Why Did You Come Back Every Summer (Charco Press, trans. Maureen Shaughnessy), the autofictional account of a young woman’s sexual abuse at the hands of her uncle, a police commissioner, and the criminal proceedings she brings. Polyvocal, mixing first-person narrative with police interview transcripts, from its title onwards this book confronts society’s keenness to blame the victim sooner than pursuing the guilty. The Gisèle Pelicot case in France has only made this book more horribly timely.

Roy Claire Potter’s beautiful The Wastes (Book Works) is one of those nice conceits – a text that takes place over a single day, its narrator taking a journey by train (geographically) and into their past (philosophically), and one that finds, in the interrogation of a barren-seeming life, rare and precious treasures. There’s a great deal – too much – going on in the mind of Michelino, precocious teen narrator of Verdigris by Michele Mari (And Other Stories; trans. Brian Robert Moore), whose relationship with an elderly groundskeeper evolves as the boy devises mnemonics to help the older man retain his failing memory. The discovery of three mysterious skeletons buried in the grounds of the boy’s home introduce a series of increasingly bizarre, adventure-story gothic twists, in a clever, slippery, fantastical and fantastic narrative. More elliptical and oblique is Han Smith’s Portraits at the Palace of Creativity and Wrecking (John Murray), whose narrator, referred to throughout by the wonderfully elusive term “the almost daughter”, is caught up in agitprop activities in an unnamed country and an unspecified era. Despite this deliberate nebulousness (the reader will quickly draw their own conclusions as to the where and when), this is a sharp, detailed depiction of youthful idealism coming up against forces that, recognising it as more powerful than even the teens themselves realise, will stamp it out violently. Set against this, a tender, awkward, tentative love story becomes particularly moving.

It’s hard to come to Gboyega Odubanjo’s poetry collection Adam (Faber) without an awareness of the tragedy that lies behind it: Odubanjo did not live to see this book published, and this knowledge – and that the collection takes its title from the name forensicists gave to an unidentified child whose body washed up in the Thames in 2001 – means that these poems become cumulatively ever more emotive and hard-hitting. Bodies in water recur and proliferate dreadfully in this tremendously powerful and emotional work.

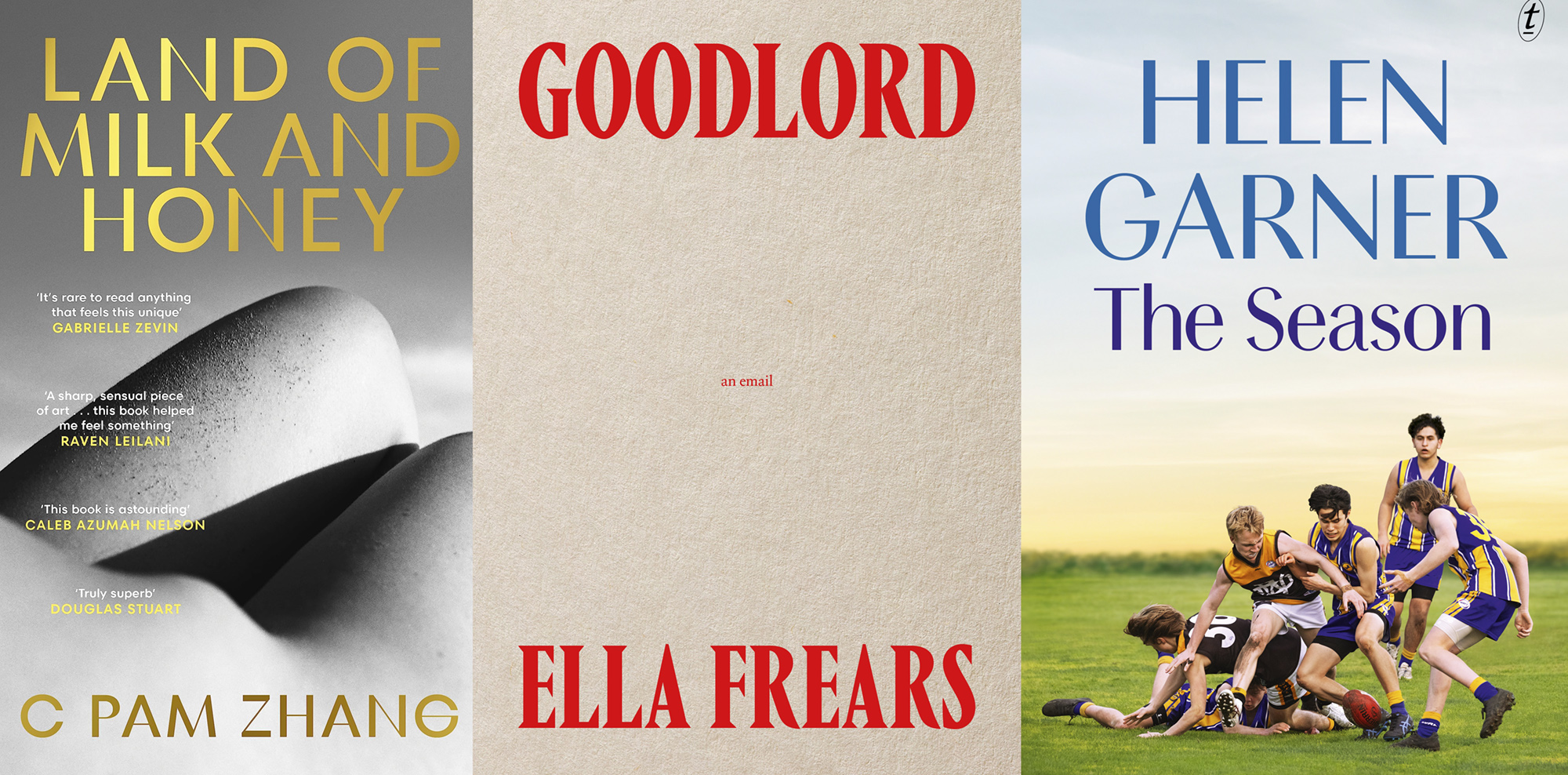

I love Ella Frears’s poetry. Her new novel in verse, Goodlord (Rough Trade) takes the form of an email addressed to a housing rental company, and its tone contains all the hopelessness and contempt and pleading that characterises such attempts to communicate with the unreachable arbiters of our lives. It’s also a very funny book, especially when its central character – describing various living situations she’s enjoyed and endured – embarks upon an artist residency that turns quickly farcical.

If you’d told me at the start of 2024 that I’d end the year raving about a book on Australian Rules Football – of which my knowledge extends little further than the old joke “I went to a fight and an AFL match broke out” – I’d have been very doubtful. But The Season (Text) is the latest non-fiction masterwork from Helen Garner, and I’ll follow her wherever her empathy and curiosity takes her. Now in her 81st year, she observes her grandson Amby’s under-16s team over the course of their winter season, faithfully attending each practice session and game, following the bemusing rules as best she can, but more fascinated by what footy says about boy- and manhood. Match scores and technical details of tackles are set dressing: at the heart of this book are the conversations between grandson and grandmother – their camaraderie and intimacy, which is of a different quality than that between parent and child – in what Garner, in a matter-of-fact summary that made my eyes prickle, calls “a season we are spending together before he turns into a man and I die”. I want, as in the last quarter of one of these games, where the underdog surges up to record an almost impossible win, for Garner to cheat fate and go on writing forever.

I came away feeling that I understood a lot of the world around me better than I had before – even if that knowledge is not very reassuring

New in paperback this year, I found Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost (Vintage), which depicts a theatre group attempting to stage Hamlet in the West Bank, deeply wise. In Land of Milk and Honey (Penguin), C. Pam Zhang posits a world of climate crisis and deep social disparity, in which a celebrity chef finds herself working for the unthinkably rich; the high concept is matched by the gorgeous prose. Benjamin Labatut’s The MANIAC (Pushkin Press) links the development of computing to the building of the nuclear bomb and the emergence of AI, and sees in all three technological arms races the same follies: inadequate checks and balances leave an inadequately prepared world struggling to contain a quasi-demonic presence unleashed by people who should know better, but simply don’t care. A parallel narrative of sorts can be found in Naomi Klein’s Doppelgänger (Penguin), in which a strange case of mistaken identity (Klein is frequently confused with women’s rights writer turned right wing ideologue Naomi Wolf, despite their now entirely antithetical politics) leads to an examination of mis- and disinformation, politics personal and global, the pandemic and propaganda. Klein’s great gift is to make you feel as smart as she is, and I came away feeling that I understood a lot of the world around me better than I had before – even if that knowledge is not very reassuring.

Finally, a key work by Romanian author Mirceau Cartarescu was this year at last published in English, in a translation by Sean Cotter (Deep Vellum, reissued by Pushkin Press) which was immediately rewarded with the Dublin Literary Prize. Solenoid is the beyond Lynchian tale of a suburban schoolteacher, who begins each day in the most mundane way – preparing a lesson plan or enduring banal staffroom chat – before events slide inexorably into the nightmarish: here are secret portals and impossible buildings, hidden codes, unearthly creatures held in huge laboratories, and – in one of the most terrifying sequences I have ever read, one that will live with me forever – a gigantic statue of a philosopher that goes on a violent rampage. The genius of Solenoid is that after each demented sequence, the story resets and our teacher begins the next day returned to his everyday existence, before the surreal once again takes hold. This is a novel that will be read and discussed for decades and centuries to come, for as long as there are still people left to read books. C

Neil D.A. Stewart is the author of the novel Test Kitchen (Corsair).

Civilian recommends independent UK retailers BookBar, Burley Fisher Books, The Common Press, Ink84 Books, Libreria and Pages of Hackney (London), The Book Hive (Norwich), Mr B’s Emporium (Bath), and Golden Hare (Edinburgh)