As the song has it, pace is the trick. When planning your trip to San Sebastián, it is vital not to do what I did and accidentally arrange two Michelin-starred meals for the same day. It’s not difficult to make the mistake; this appealingly unassuming town has several of the world’s most renowned restaurants, and the densest concentration of stars anywhere on the planet.

every second shop sells dust-coated medical supplies straight from a nineteenth-century carpetbag

I was in love with San Sebastián even before setting foot in any of the famous eateries. While there’s a grouping of high-end properties (such as the Hotel Maria Cristina) and new developments either side of the bridge that takes you into the heart of the Old Town, a few minutes’ walk further out places you in one of those slightly eerie European towns full of slightly dilapidated art nouveau-styled mansions which you could probably buy for buttons; whose every second shop sells dust-coated medical supplies straight from a nineteenth-century carpetbag; and whose doorways are elaborately decorated portals whose decorations (lightning bolts, stylised webs of metal bars) suggests the entryway to the headquarters of some ancient cult. Across the river, a vast brutalist block (a school building? Multi-storey car park?) sits windowless, abandoned, a connective bridge that sprouts from its top floor disappearing into the bounteous forest greenery climbing the hills out of town.

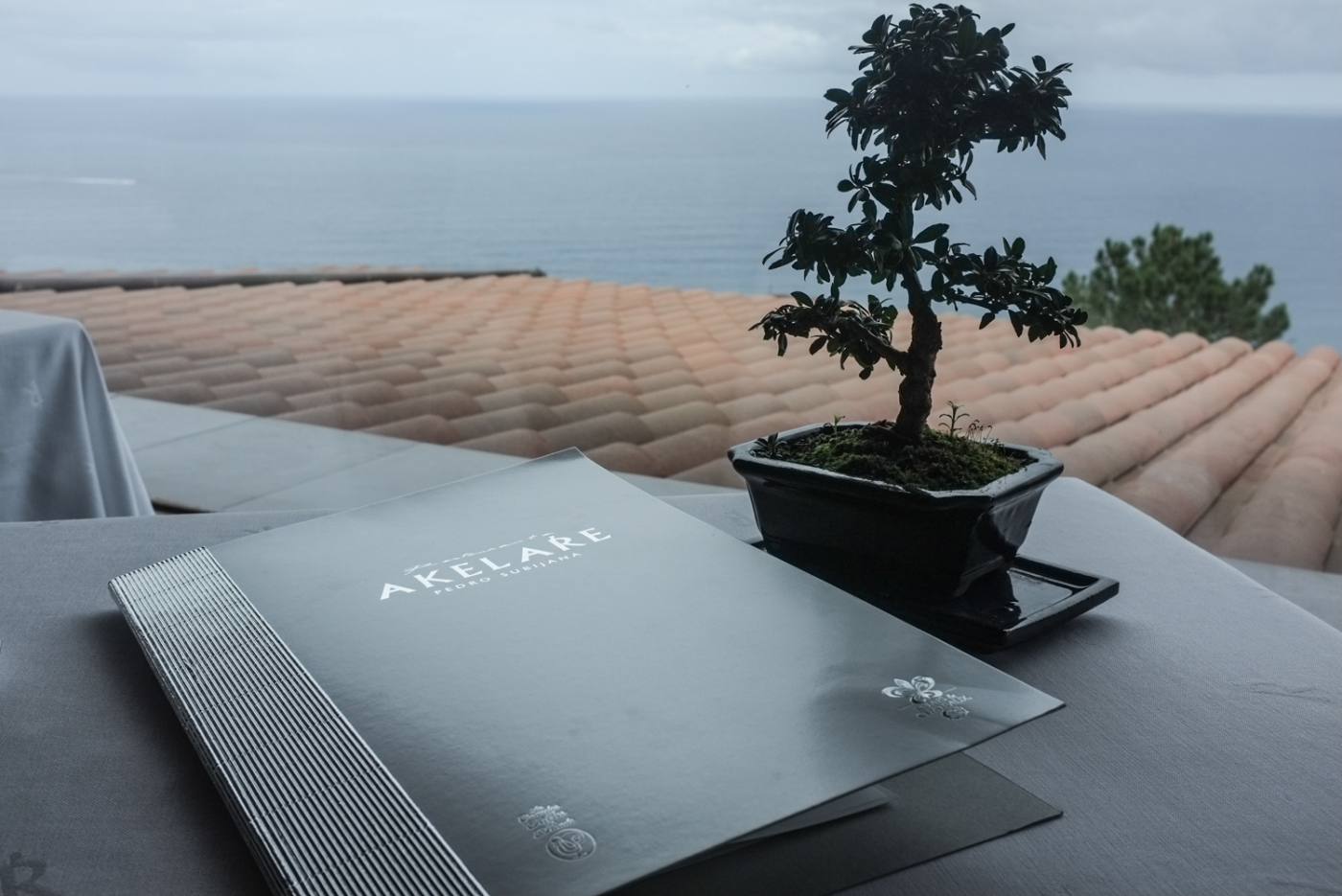

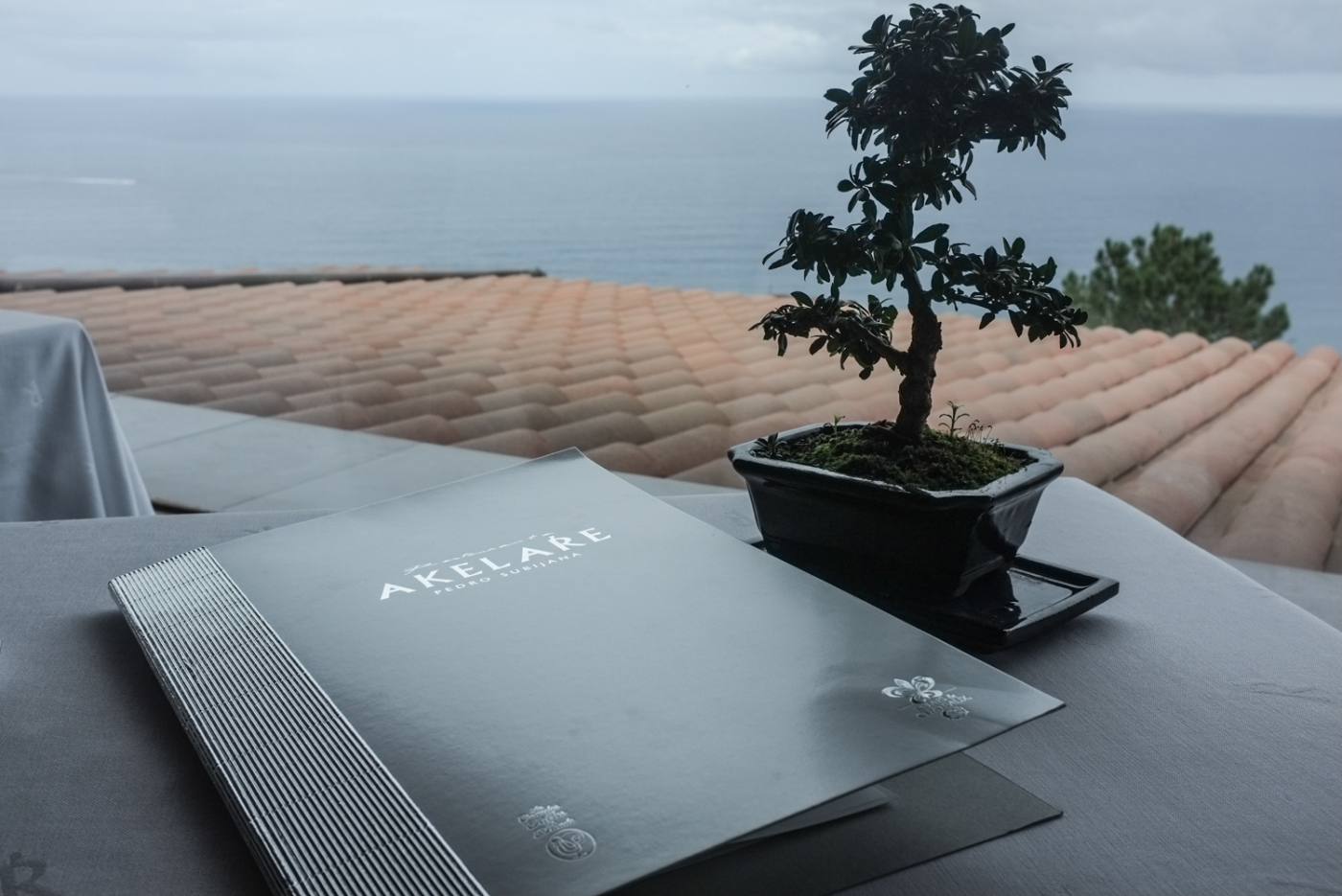

At Akelare, high up in those hills, Chef Pedro Subijana offers guests a choice of one of two different tasting menus, effectively doubling up the number of dishes you get to try in an already comprehensive four-hour lunch extravaganza. (Fortunately, both series of dishes are excellent: he’s not pitting diner against diner in a contest.) As I was enjoying cuttlefish, suckling pig and hake on the Aranori (“grape”) menu, my companion was tucking in to the Bekarki (“rocket”) menu’s turbot, pigeon with molé sauce, and a delightfully weird puzzle box containing fragile, intensely sea-savoury shavings of desiccated cod and a “crystallised” piece of the fish. His menu contained hake too, and more specifically kokotxa, variously translated as the fish’s neck, throat, or dewlap; this minuscule shred of softly gelatinous fish flesh is the local delicacy; you’ll find it on every menu in San Sebastián, prepared traditionally or played around with (Akelare’s version involves presenting a cube of hake fillet beside a fake kokotxa: a bowtie shape made of potato, delicately “painted” in grey and silverish tones until it resemble the scaly real deal).

Salad, Martin Berasategui style

If the playfulness doesn’t always make for such convincing illusions (sautéed foie gras onto which are heaped great quantities of “peppercorns” and “salt flakes” very obviously made of sugar), the flavours remain consistent

This is playful, clever food: throwaway “jokes” on the plate, such as the puffed potato crisp in the shape of a pig that accompanies my suckling pig dish, and which is clearly fiendishly difficult to make well, have been researched and developed to the nth degree. My own sub-Michelin scoreboard prioritises inspiration, quality of ingredients, perfection of cooking, mastery of technique – and Akelare is in a different league on this last count. Why not devote dozens of man-hours to perfecting a potato crisp that lunchers will gobble up in two bites? Other dishes play more elaborate pranks – what appears to be a halved peach is a hollow white chocolate shell, painted to resemble the fruit as precisely as possible, which contains peach compote. If the playfulness doesn’t always make for such convincing illusions (sautéed foie gras onto which are heaped great quantities of “peppercorns” and “salt flakes” very obviously made of sugar), the flavours remain consistent – and excellent. Enough dishes eschew playfulness that the meal doesn’t just come over as an ongoing series of gimmicks – and some are simply beautiful. A cluster of chocolate leaves, sweet fake flower petals and mint leaf is arranged on what at first appears to be a glazed orange plate – until your spoon cuts through what proves to be a flawlessly smooth layer of sweet-sour orange set sugar gel. I recall being warned when I was small that I’d scrape off the pattern if I chased any last scraps of food round my plate; at last, the delightful experience of doing just that.

Handwritten wine list at Akelare

Invited to view the kitchen at Akelare post-lunch, we nodded, impressed, at the vast expanse of scrupulously clean stainless steel and industrial gewgaws. Without chefs at the stations, it’s difficult to get a sense of the real kitchen, however: does it all run smoothly? Are there tantrums? You’d imagine not, especially after one last splendid detail: the sommelier, a very tall, slight gentleman of the Jeeves school, who has introduced each wine handsomely, glides over at the end of the meal, and hands us a handwritten list of the wines we’ve sampled, the list illuminated with bunches of grapes, barrels and excitable bottles of champagne. “Even a humble sommelier can do something to help,” he murmurs, and it might be the altitude, or the quantity (and quality) of wine, but I feel a bit of a tear in my eye all of a sudden. Add personality to the list of components that turn a great lunch into a stellar one.

I checked my watch as I rolled out to take a taxi back down the main part of San Sebastián. I’d been at lunch for four hours. It was an hour and half until dinner at Mugaritz.

The burger at Arzak

Sensibly, I opted for just one meal the next day, though it proved to be a whole day’s worth of fun. Arzak, run by Juan Mari and his daughter Elena, is possibly the best-known of the San Sebastián restaurants. A visit there is not just a matter of turning up, being seated and served and then cut loose; I was shown around the kitchen, shared snacks with the staff in the “mess room”, inspected the taste lab where new dishes are experimented with (a plate under preparation looked as though it had been left out in the woods for autumn leaves to alight randomly on it), delved into a cellar where ranks upon ranks of bottles can be examined via lightbulbs hung on coat hangers, and visited a store cupboard on whose rows and rows of shelves were containers for every spice, herb, crumb, and ingredient you could think of, plus a couple you’d never imagine: I was delighted to spot one labelled “Werther’s Originals”.

While other family members are present – Juan Mari’s wife; Elena’s husband, the architect who designed the restaurant – it’s father and daughter who run the show. Theirs is a symbiotic relationship, built up over years of working together: they bicker agreeably, zing in-jokes back and forth, laugh together. They stress that they are equals (though I don’t think Elena uttered one sentence her father didn’t interrupt or contradict, it was all good-natured), and there’s also the sense that the daughter – now nominally in charge of the kitchen, with Juan Mari taking a step back – has always been the grown-up one, her father the joker. At one point, seeing me eye a strange speaker-grille device on the kitchen wall, Juan Mari runs over, pulls down a handheld microphone from the side of the device, and belts out some instruction over the tannoy. It is not that big a kitchen; one feels he just enjoys pretending to be a submarine captain giving orders.

Juan Mari runs over, pulls down a handheld microphone from the side of the device, and belts out some instruction over the tannoy. It is not that big a kitchen; one feels he just enjoys pretending to be a submarine captain giving orders

The food is theatrical, fun, and utterly unsurpassed. Here again are technique, craft, and inspiration in perfect balance. Monkfish fillet comes encased in a dayglo green bulb something like a spherical poppadum, which the server contentedly smashes apart using a little hammer. A wagyu burger, bedecked with tiny sweet beets, flower petals, and two butterfly-wing fragile potato “chips”, is served on a glass plate under which is slid an iPad showing a short film of flames, so that dry ice, curling off the food, appears to be smoke from artificial flames. Playfulness isn’t ever just for its own sake, but has been thought about, and has emerged from a sort of theoretical framework the Arzaks have developed, in which nostalgia and wild inspiration both play parts. A dessert based around Elena’s memories of childhood visits to the circus is presented in a miniature big top tent; lift away the conical “roof” and beneath are three cute little circus-themed sweets, including lollipops in the shape of a strong-man’s dumbbells. And lateral thinking on the Arzaks’ part has led to the truffle, that ingredient over-used by restaurants seeking to justify exorbitant meal prices, being represented by its chocolate-variety namesake: a misshapen lump the size of your fist, dusted in cocoa powder and doused in chocolate sauce; its texture incredibly dense, its flavour rich and earthily savoury-sweet, it really does seem like something dug up from some fecund field. (Oh, to live in a place where chocolate truffles grew wild!)

Akelare

Martin Berasategui – quickly rechristened by we non-San Sebastián natives as Martin Beuh, to forestall slurring the name after a few glasses of the restaurant’s own branded 2012 Grenacha – was disconcertingly empty when we visited for lunch: in fact, we were the only guests in that large dining room, putting us at the centre of attention of a six-man staff who, thankfully, knew to keep their distance and not make us feel intimidated or put-upon. Once again, you’re up in the hills here a little outside San Sebastián, looking out on rolling fields and deciduous woods nearly denuded of leaves but still retaining some shreds of autumnal colour. The occasional farmer trudges past, seemingly oblivious to (or perhaps deeply censorious of) the Michelin-starred place on the hillside above him. “What would you do,” asked my companion, struck by the peaceable scene, “if you looked out, and way down there in the valley you saw someone get killed?” The answer is obvious: finish lunch, make a phone call, then order another glass of wine while I wait for the police to arrive.

“What would you do,” asked my companion, struck by the peaceable scene, “if you looked out, and way down there in the valley you saw someone get killed?”

The menu is presented as a compilation, “The Best of Martin Berasategui” (I wish they’d gone the whole hog and christened it Now That’s What I Call Martin Beuh!) which, as with the best of best-ofs, leaves you both agog at its own quality and deeply intrigued as to what didn’t make the cut. Here’s a plate of purest green – lime gel, cucumber, and crumbs of lurid green sponge cake – which is, for something served up mid-December, impressively spring-like. Here’s a glossy pool of squid ink, studded with bean sprouts, held circular by a circlet of foam: it resembles a scrying glass made with black mirror, the “handle” a crispy seafood crouton. Arrangements are beautiful, rather than showy: what’s unprepossessingly termed a “Warm vegetable hearts salad” proves to be a plateful of approximately fifty different elements, from baby asparagus and basil leaf to passionflower and pea gel to discs of lobster, each meticulously placed on a plain white plate. It is spectacular, and simple: ingredients this good don’t need playing around with. Whatever’s in the water at San Sebastián, it is making for chefs making, in turn, some of the finest food you can have, in which thought, technique, flavour and fun are perfectly balanced.

The near-silent team ushered us into the kitchen after we’d finished lunch. Not only were we the only diners, all evidence of the elaborate preparation that had gone into our meal had vanished: bereft of staff, the kitchen contained just dormant machinery, burners gone cold, pristine stainless steel counters. In a way it was fitting that food this good could seem, for an awed moment, to have come about by magic. C

relaischateaux.com