Derek Jarman 1942-1994 | Avant-gardener

2014 marks 20 years since the death of the Great British filmmaker, painter, set designer, gardener, diarist, activist and Alternative Miss World 1975, Derek Jarman. The year is being marked with events at King’s College, the BFI and the V&A. With so many of his acolytes (Sandy Powell, Cerith Wyn Evans, John Maybury, Tilda Swinton, Simon Fisher Turner et al) at the top of their game in mainstream culture, now seems an apt time to reassess Jarman’s art and its long term impact.

Derek Jarman’s ongoing appeal to many is that, while he injected fury, punch and confrontational politics into his output, he also fashioned a striking and alluring style – rustic, hedonistic, pagan and occasionally occult. His world was cliquey, cool, and quirky in a quintessentially English way: he always seemed to have one foot on the dance floor of Heaven and the other in the upstairs tea room of Maison Bertaux in Soho.

Like Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol, Derek Jarman couched his brand of counterculture in a gritty chic that has drawn subsequent generations to it, including art students who weren’t born when his creative light dimmed two decades ago. He aligned himself with the most intriguing characters of the 1970s and 1980s underground, including Andrew Logan, Duggie Fields, William Burroughs and Genesis P-Orridge.

The Jarman style is absolutely distinctive: the painterly light and frame of his feature films and blown up Super 8 movies; the palimpsest of his pop videos. There are the flashes of edgy contemporary dance and women spinning like banshee dervishes in torn gowns, flaming Union Flags and derelict buildings, and the omnipresent male nude. The Jarman aesthetic lives on: his analogue style has a warm authenticity, while the “look” of Prospect Cottage and Dungeness debris fill the pages of design magazines the world over. As much as anything, his work – from the films that he battled so hard to bring to fruition, to his candid diaries – captures an avant-garde era in London that is gone forever, and much missed.

Jordan as Amyl Nitrate in Jarman’s punk movie Jubilee, 1978. Jordan worked at Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s World’s End store in Chelsea. Westwood hated the film and created an “open T-shirt to Derek Jarman”, which she sold in-store, with her critique of the movie: “I had been to see it once and thought it the most boring and therefore disgusting film I had ever seen.”

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called Jarman’s arresting, magical, irreverent interpretation of The Tempest “a fingernail scratched along a blackboard, sand in spinach, a 33-r.p.m. recording of Don Giovanni played at 78 r.p.m. Watching it is like driving a car whose windshield has shattered but not broken.”

Derek Jarman occasionally took on purely commercial pop promo projects to generate much needed income. The video for Wang Chung’s “Dance Hall Days” is one such curiosity. He infused it with personal nostalgia, using home movie footage of his mother, as well as imagery from The Wizard of Oz, the first film he saw at the cinema, and a revelatory experience for him.

The Queen is Dead (1986) is a 13-minute film set to three of The Smiths’ songs: “The Queen Is Dead”, “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out”, and “Panic”. Jarman was creating a new cinematic language through the pop promo, and his blown-up, manipulated Super 8 footage. “Music video is the only extension of the cinematic language in this decade,” wrote Jarman in The Last of England, “but it has been used for quick effect, and it’s often showy and shallow.”

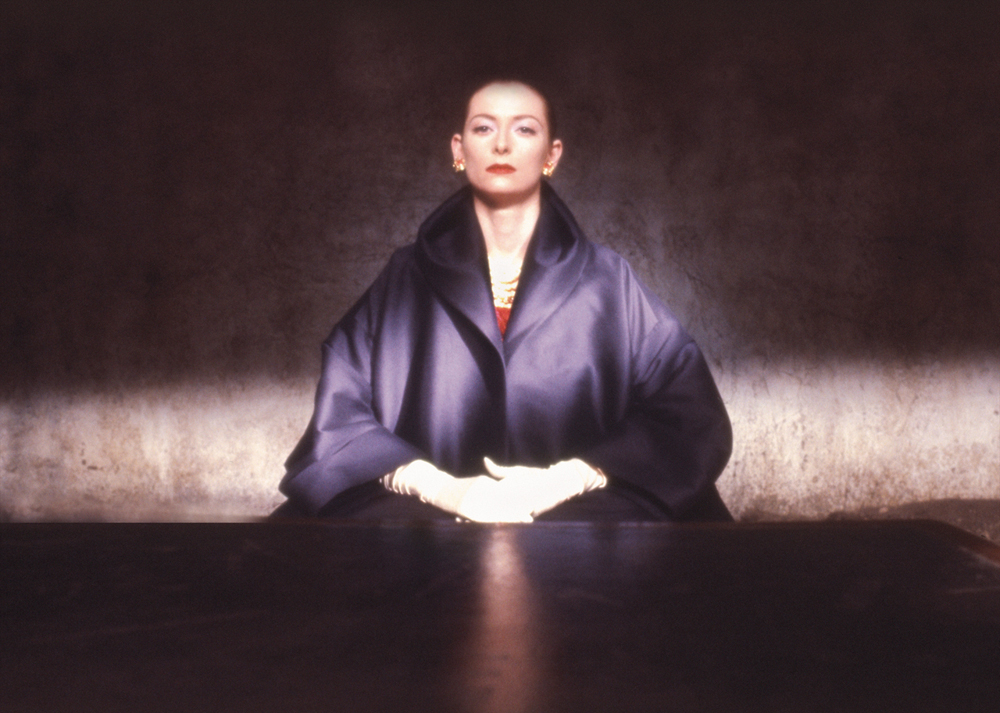

Tilda Swinton in The Last of England. Jarman’s 1987 film was a furious portrait of cultural nihilism in England in the 80s. “I improvised [the film]”, he wrote in his diaries. “No script. Scripts are the first restraint; the commissioning editor opens the mail and writes his hurried replies: ‘Dear Mr Dickens, the script for your new novel Bleak House is much too complex’.”

Tilda Swinton in Jarman’s Edward II, 1991. The film is playfully postmodern, and mixed modern-day art direction with medieval style, as well as performances from DV8 Physical Theatre and Annie Lennox. Jarman had a studio budget, but was as subversive as ever: “How do you get someone to commission a film about a gay love affair? Take a dusty old play and violate it.”

When Derek Jarman told the sculptor Maggi Hambling at a party that he had bought Prospect Cottage in Dungeness and planned to write a book about its garden, she said: “Oh Derek, you’ve finally discovered nature.” “I don’t think it’s really quite like that,” he replied (recalling, in his diaries, that this made him think of Constable and Samuel Palmer’s Kent). “Ah, I understand completely,” said Hambling. “You’ve discovered modern nature.”

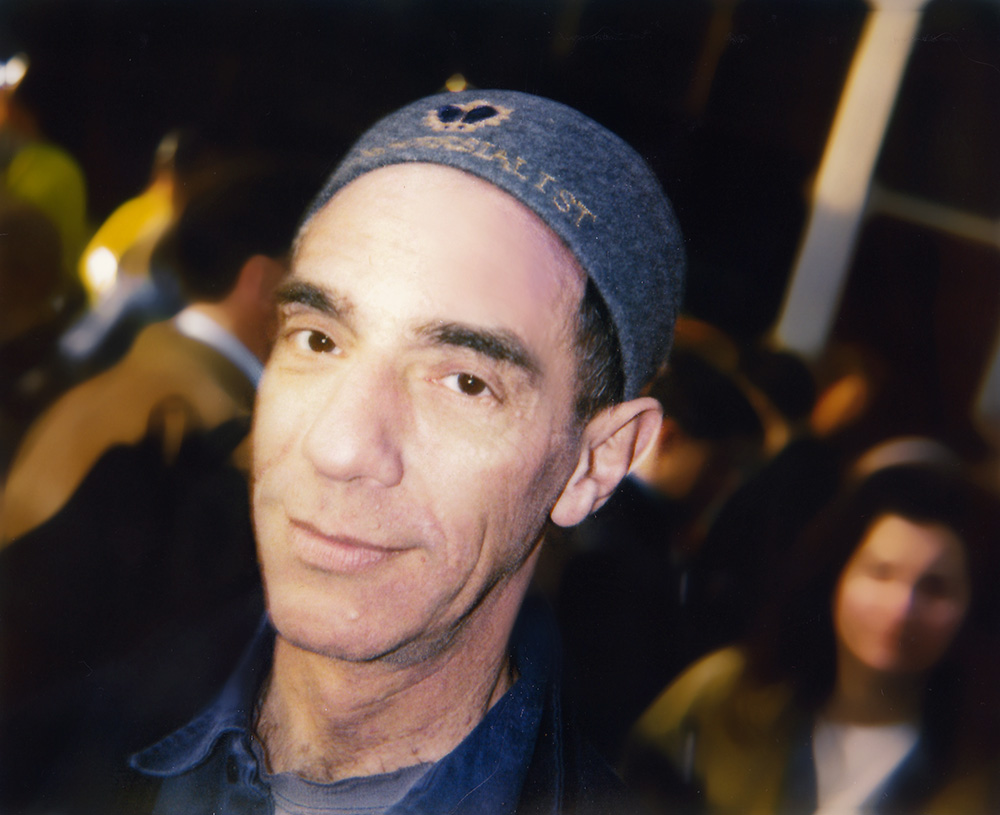

“People say to me, You make fantastic films and I say, No, I make documentaries.” Derek Jarman in Soho, 13th February 1993, by Mark C.O’Flaherty. Jarman was buried one year later, wearing the same hat – bearing the word "controversialist" – in St Clement's Churchyard, Old Romney, Kent.