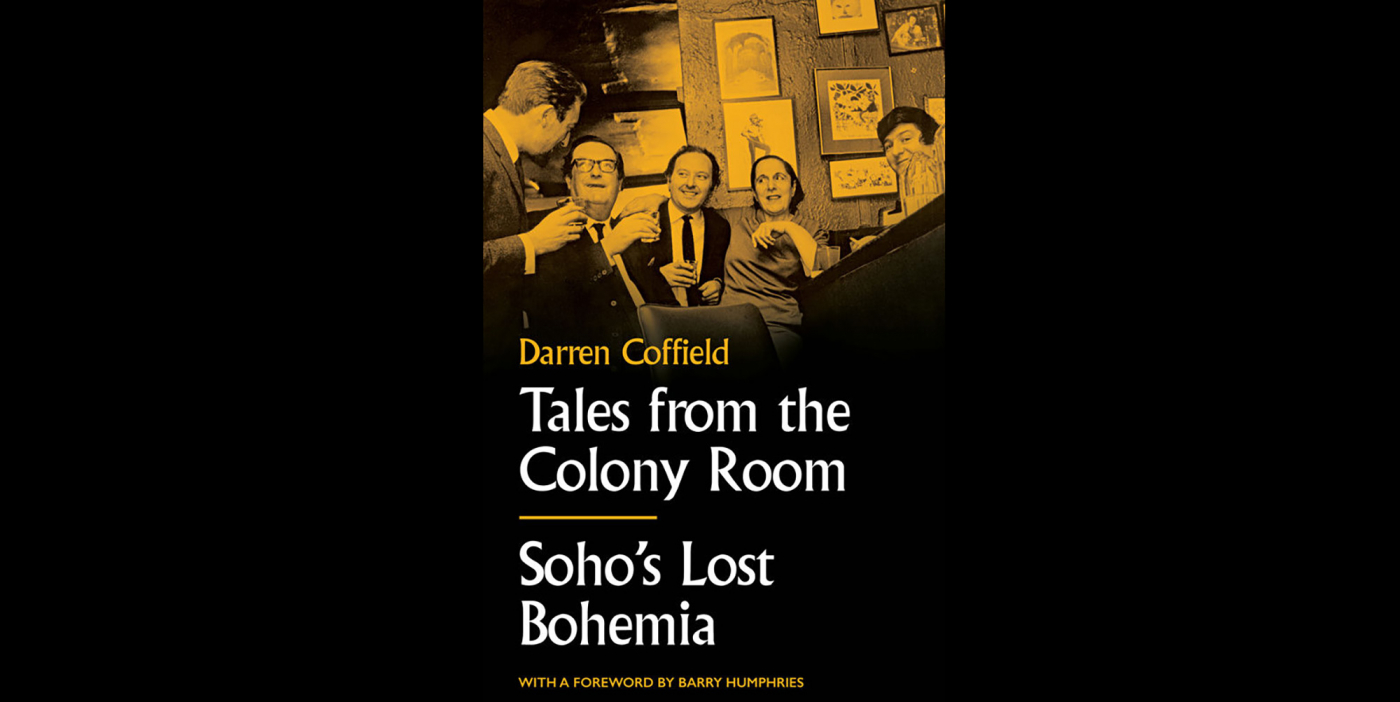

“Bring out your dead!” | Review: Tales from the Colony Room by Darren Coffield

The book detailing the story of the Colony Room – Soho’s most celebrated den of inequity from 1948 until 2008 – is a gruesome horror story, says Mark C. O’Flaherty

The book detailing the story of the Colony Room – Soho’s most celebrated den of inequity from 1948 until 2008 – is a gruesome horror story, says Mark C. O’Flaherty

If this is Soho’s Lost Bohemia – as the subtitle of Darren Coffield’s book suggests – then good riddance to it. All Londoners have their own Soho, but most old enough to remember a time before Polpo and G-A-Y will agree that the identity of the era was forged in the heat of 1950s post-war hedonism. The spirit of that Soho lives on in Bar Italia’s neon and caffeine and the pages of Colin MacInnes’s Absolute Beginners. And, yes, a big part of that culture was the Colony Room, the much-mythologised clubhouse for groundbreaking artists and day drinkers. With the area decimated in the 2020s by Crossrail, Covid and a cultural shift of London eastwards, there’s a powerful nostalgia about how things used to be. Regarder the hot tables at Noble Rot, which recently revived the storied Gay Hussar space. Using a substantial archive of taped interviews – the very existence of which suggest that all concerned were remarkably, if unsurprisingly, self-aware – Coffield has edited together a vivid oral biography of the club that isn’t so much warts and all, more abandoned abattoir lousy with flies and maggots. But it is compelling. As soon as I finished reading it, I found myself dipping back into choice chapters. And I will return time and time again.

Apart from soiling themselves, most of the members seem to have devoted their time to being as vile as possible to one another

Queer before queer was defined, the club and characters in Coffield’s book are almost uniformly grotesque. The varying degrees of queerness and creativity of the members gave them license to be wildly repellent. Fragrant drunks stumble in and defecate discreetly on a banquette in the rear, while 99% of the room seems to be keeping an eye out of the 1% that actually has the funds – or “the handbag” in founder Muriel Belcher’s parlance – to buy a round. Apart from soiling themselves, most of the members seem to have devoted their time to being as vile as possible to one another, while drinking themselves, as quickly as possible, to death. Everything about it is fascinating, but much of it seems pathetic. Surely, I kept wondering, page after page, it’s not actually hedonism if it doesn’t seem to be actual fun? As a reckless 80s/90s club kid, I found myself being judgy. What success and glory is there in being wholly incapacitated, or dead? Today’s conservative Millennials and Gen Z readers will view all this as they would a TikTok from a more prurient planet, and recoil.

John Maybury’s Love is the Devil

The only individual who seems to be having a genuinely nice time is Francis Bacon, who drifts around on a cloud of celebrity, raining money down on acolytes and enemies alike to get the attention he so desperately craves. Oh, and Muriel, of course, who ran the first third of the show, from the club’s opening in 1948 through to the end of the 1970s. No doubt formidable and fabulous in her own way in person, in Coffield’s transcripts she comes across as a foul-mouthed crone. Even the place itself – upstairs at 41 Dean Street – is depicted as a kind of poky hell hole. There is no doubt that the club had a unique patina, a lot of quirk, and contributed to the local colour and gaiety of life, but from fecal matter to stale fag smoke, you can almost smell it off the pages of this book, as well as see its gangrenous green walls. It would be disingenuous to single the Colony out for a lack of sophistication – after all, before the 1980s, shelf-temperature Britvic behind the bar was standard for London – but in these pages, it really does sound gratuitously awful. Which, of course, like truly bad service in a restaurant, makes for fabulous entertainment. While reading the book, I took time out to watch Melvyn Bragg’s South Bank Show on Francis Bacon from 1985, and John Maybury’s Love is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon from 1998, which turned Colony regular Daniel Farson’s biography The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon into a low-budget drama with stagey, painterly visual flair and a lot of favours from club kids (Bacon’s muse Sue Tilley and the late DJ Talullah seem to be perpetually lurking in the background). For many, the Colony – like Max’s Kansas City and Isherwood’s Berlin – represents a subculture that leaves you hungry for more.

John Maybury’s Love is the Devil

You may have longed to be transported to the 1960s for an evening propping up the bar with Lucian Freud and gossiping with George Melly the boogie-woogie man. But one of the surprising joys of the book is that it makes you realise that, actually, you probably don’t want to. Maybe a later era would have suited you more? Or not. The final years of the Colony were marked by a new popularity among the Blur and Damien Hirst crowd. Truly death on toast. By then what was left of bohemia had moved east to Shoreditch and beyond, and the club’s final proprietor – Michael Wojas – was running it into the ground, literally smashing it up in 2008 before dying destitute and a heroin-riddled mess at 53. At one point in the book, even club member Sebastian Horsley slags off Wojas for his intolerable drug use. Which is a bit like Myra Hindley laying into Mumsnet.

For most of the book, Coffield sensibly keeps Bacon in the foreground, while the hangers on drift in and out of consciousness. The guest list is fascinating, of course: Tom Baker rocks up on Saturday afternoons to narrate himself as Doctor Who on the TV behind the bar, drinking pints of gin and tonic, while what’s left of Nina Hamnett – ‘It Girl’ of Paris in the 1910s, artist, writer and muse to Modigliani and Picasso – decays on a stool in the middle of the century, until she is parodied as part of a radio play in 1956, and hurls herself out of her window shortly after, impaling herself on the railings outside.

While I was immersed in Coffield’s book recently, London was enduring Lockdown 3.0. Soho is a ghost town. It’s impossible to say what it’s going to look like in the next six months, or next year, but no matter what bland, corporate coffee and no-reservation dining opportunities fill currently vacant spaces, it will forever be haunted. Tales from the Colony Room is more a horror story than a biography, but like a lot of horror, it is compelling. And let’s face it, no one is going to be splicing together a rollercoaster memoir of The Breakfast Club in years to come, are they? C