Cooking the mountain | Atelier Moessmer Norbert Niederkofler, Brunico

Come for the krapfen and rollen, stay for the canederli and strudel. David J Constable heads to the South Tyrol for Norbert Niederkofler’s culinary marvels

Come for the krapfen and rollen, stay for the canederli and strudel. David J Constable heads to the South Tyrol for Norbert Niederkofler’s culinary marvels

I have written about Norbert Niederkofler before. Mostly, though, I just talk about him. And happily so. He deserves all the written and verbal praise that comes his way. It’s just that I find it so much easier to write Niederkofler than to say it, and even that Denglisch endeavour takes me several attempts. He’s Italian but with an obvious Dolomitic surname. His cooking is both. It’s mountain grub, from the Marmolada down to the valleys. So much so that he has deemed this approach “Cook the Mountain”, referring to his dependence on local suppliers, all set within South Tyrol and its swinging seasons.

In Norbert’s kitchen, there is no olive oil. No tomatoes. No lemons. No foie gras. No caviar. Nothing from France or Spain. No New Zealand lamb. No British strawberries. To go from foraging in a land that spends a lot of the year frozen and dark to his current position on top of the international culinary world is an impressive leap. Three Michelin stars plus the green for sustainability are always impressive. But when the chef chooses not to import and lean on luxury, preferring instead to restrict the offering of ingredients, well, that’s incredible.

“I grew up without a supermarket on the corner. Despite this, there was always plenty of food on the table, even in winter. So I had to set up my own supermarket to see me through the lean months.”

With patience and a nagging persistence, Norbert has made high gastronomy in a place not known for it. South Tyrol and the Dolomites region of Italy’s northern reaches have a very particular diet. It’s krapfen and rollen, canederli, strudel and a lot of polenta. This is hearty, stodgetastic mountain food; feeding to warm and nourish. There are not many restaurants up here paying attention to fine dining or cooking as an act of love. The trattorias and chalet dining of southern Tyrol are mostly geared towards survival. It is food to energise just enough so that you can ski back down the mountain without fainting and falling on your arse. Norbert’s focus, however, emphasises the glories of Alpine traditions, its produce and old recipes, modernised.

Departing the three-star restaurant St. Hubertus two years ago, there was mumbling through the mountains as to Norbert’s next move. The Aman group purchased the Rosa Alpina Hotel and its adjoining restaurant, with both subsequently torn down. For Norbert, there were new ventures in Venice and Milan, with an overseas project alongside NEOM in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. However, the Dolomites never stopped calling, the mountain boy always returning home to the snug comfort of the snow-peaked crags.

Atelier Moessmer Norbert Niederkofler

Norbert also continues to oversee the majestic AlpiNN restaurant in Kronplatz with his business partner Paolo Ferretti and chef Fabio Curreli; the building hanging from the side of a mountain, an impressive glass structure at Plan de Corones, 2,275 metres high. Having dined at both St. Hubertus and AlpiNN, the architectural differences are clear, but the kitchen attitude is the same – to support and promote the region, the countryside, the mountains, chomping on weeds, berries, eel, mutton, fungus, fermented things, sharp things, unripe things.

Now he’s back in a new restaurant, relocating from San Cassiano to Brunico in the heart of Kronplatz, the largest town in South Tyrol. The brand new, multi-million Euro restaurant occupies the former villa of the cloth factory Moessmer, which, as well as employing and sustaining a significant slice of the Brunico populace, is one of the oldest fabric producers in the world. Established in 1894, they have supplied the likes of Prada, Dolce & Gabbana and Louis Vuitton. The company is also responsible for dressing royals from the great Habsburg court. I would recommend Googling Francis Joseph, King of Bohemia, for further examination of his dapper threads and to observe his audacious moustache, which resembles an electrocuted ferret.

Atelier Moessmer Norbert Niederkofler

This new restaurant location is fitting for such a lauded chef. Located alongside the fast-flowing Reina River and adjoining Passeggiata, and within the former villa, the return of this local boy has further energised the city. Installing a restaurant here has heralded a thrilling new life for the Moessmer company while raising the culinary bar in Brunico and stylistically aligning fashion with food, as is the marketable culinary fad right now. Partnerships are already established between Massimo Bottura and Gucci, Niko Romito and Luca Fantin with Bulgari and Mory Sacko with Louis Vuitton. The universal truth is that neither hankers over the other’s businesses but unified in commerce, each proffers.

Arriving for lunch on a chilly September afternoon, I am led up the villa staircase through the large imposing doors; and encouraged to ring the doorbell, which is the restaurant-in-thing this year. From there, I’m taken to a couch bar area where I sit, drink local Hausmannhof bubbles and enjoy snacks. I began with little treats, plates and rocks, upon which were tartlets with beetroot and cannolis of duck speck and potatoes and mushrooms. There were also tacos made from corn, filled with raw char, and “pastin” of local veal that looked like tartare and had the perfect percentage of fat, piqued with yellow dabs of yolk-soy emulsion, melting like snow on my tongue.

So far, this is all very Norbert. Explorative cooking, digging into his heritage and the locale to uncover the wonders of mountain life and its cuisine. Forging the necessary relationships with local organic farmers, it is they who drive and dictate the menus. As such, the cooking at Atelier Moessmer is a departure from molecular acrobatics and more like a seasonal lucky dip or culinary improv, deceptively simple, while requiring the nerve and the ability to sell gnocchi made from beetroot and decorative mountain leaves passed off as salad.

“It was the memories of childhood that helped me,” he says when I ask him about the new menu. “I grew up without a supermarket on the corner. Despite this, there was always plenty of food on the table, even in winter. So I had to set up my own supermarket to see me through the lean months.” I ask if this was the foundation of “Cook the Mountain” and if it can all be attributed to childhood lessons. “Except these old techniques had to be dusted down and applied again”, he says.

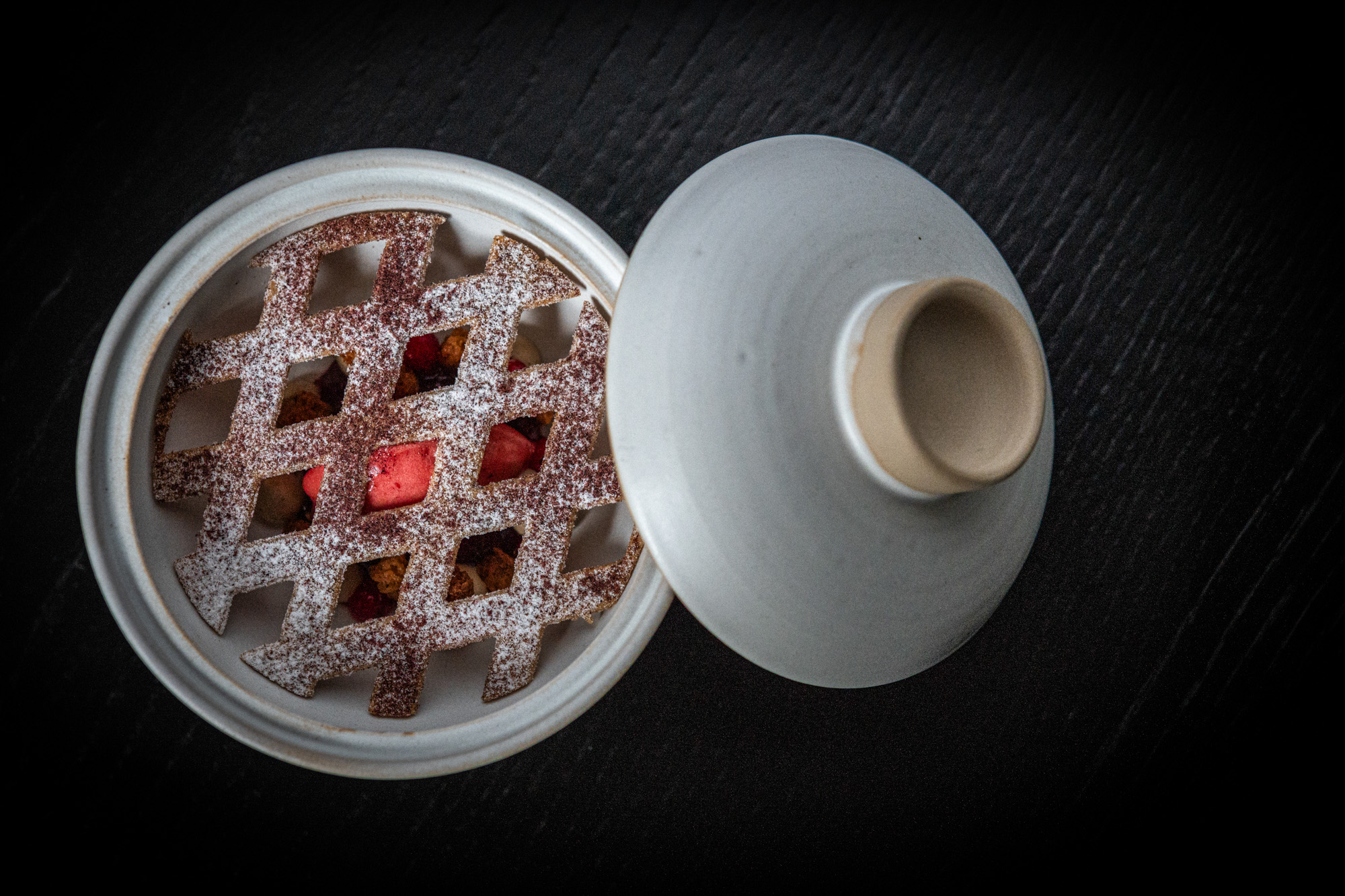

Linzer torte

But Norbert isn’t alone in this new venture. His team is mostly the same as the late St. Hubertus, including Lukas Gerges and Mauro Siega, as restaurant manager/head sommelier and executive chef. All of the team appear alarmingly young. Scanning the kitchen, it’s as though they’ve won a restaurant experience as part of a culinary school raffle. Given the tenderfoot complexion of the setup here, it makes the kitchen output all the more impressive.

An outstanding dish of larch wood smoked trout with a fire-baked shallot and celery oil sauce was followed by a creamy risotto with Jerusalem artichoke and crumbled black pudding, which melted into the warm, pearly mix. The former is enormously rich and moreish, and a timely course for such a brisk Tirolean day. In the south of the country they produce sanguinaccio from pig’s blood and cream, sometimes chocolate and candies, though in the upper Dolomites, the recipe remains the more rugged, barley, oats and pork fat variation. A brief aside, one 15th-century English recipe I found notes the use of porpoise in the pudding, eaten exclusively by the notability.

There was “Ventrigli”, or chicken gizzards; veal tongue from the smoker, the fleshy clapper glazed with a mountain chimichurri mix of burnt roots, salsify, celeriac, blackened shallots, preserved parsley stems alongside a pickled mustard seed horseradish and frozen barberries; and then deer cooked over fire and glazed with smoked fat, seasoned with burnt thyme salt, which had great flavour and the faint woodland whiff of the wild. Norbert being Norbert, there are no ovens or hobs in the kitchen because, well, that wouldn’t be very mountainous and outdoorsy, would it? Instead, it’s all about fire, Mauro cooking meats over a flame so that each is touched by the hot ribbons without ever being over or underworked, and emitting the full flavour of the product.

Mountain salad

I drink a lot of water because it’s so good. Not branded or sponsored or purchased to appease some global award sponsor and not plastic bottled. “When you talk about sustainability, you have to start with water”, Norbert tells me. In 2019, thanks to a collaboration with Best Water Technology, AlpiNN became the first “bottle-free zone” in Italy, renouncing the purchase and use of single-use plastic bottles. Atelier Moessmer follows suit, and you won’t find a better drop of aqua anywhere. Pure, proper mountain spring. The pails are fetched from the top of the snow-capped peaks by Lukas, who footslogs over miles to achieve and dispense the perfect drop of mealtime hydration; lifting heavy pitchers onto his shoulders and carrying them down the side of a mountain, through fields and verdurous pastures, straight through the doors of the restaurant. None of that last part is true, but I hope that it paints a picture of the H2O quality and the environment in which I ate lunch.

Water is the hospitality craze right now, some restaurants going as far as to employ a water sommelier. It is the toast of the self-righteous, the trumpet call of the pharisaic blabberer

Water is the hospitality craze right now, some restaurants going as far as to employ a water sommelier. It is the toast of the self-righteous, the trumpet call of the pharisaic blabberer who questions and scrutinises everything. I couldn’t give a fudge about branded, bottled aqua; give me tap every time. But then, water from the faucet of a UK kitchen is nothing to shrug at, Italy either. Global governments have set out legislation, proselytising “water as a human right”. It is a real-world problem. The fact that 1.1 billion people can’t get a clean, clear drink shouldn’t be overlooked. Doing away with plastics and corporate trading agreements here is something to be applauded. The mountain spring is there, and it is natural and bountiful. Another reason why I am so happy to talk about Norbert, whose CARE’s project was created to gather the industry and implement a more caring and conscious approach to the world, promoting ethical practices inside and outside of the kitchen.

A couple of desserts wrapped up lunch. Baked Tyrolian apple compote, and a linzer tarte, the shortbread traditionally criss-crossed and placed upon a chestnut cake and beetroot sorbet with bone marrow caramel. Both demonstrated the talents of the pastry section, paying homage to the sweet treats of South Tyrol without being too cloying and noxious; a deep-fried strauben or hasenöhrl now would have finished me. On the way out, I passed a table spread with petit fours and filter coffee. Departing treats of mountain rocher, buckwheat and honey truffles and flap-jack-like chestnuts with cherries completes what has been a swaggering Dolomiac spread, a lunch boastful of the region and efficacious of its bounteous producers. Again, all very Norbert. And now, Lukas and Mauro, too. All accentuating the glories of mountain life and its cuisine. C

Atelier Moessmer Norbert Niederkofler, Via Walther von der Vogelweide, 17, 39031 Brunico, Italy

ateliernorbertniederkofler.com