London 1996: The greatest fashion show on Earth

One of the last things I heard about Lee McQueen – via a friend who had gone back to his house for a particularly drunken one-night stand – was that he’d quite like to grind a broken glass into my face. “How very fashion,” I thought. Despite being on lunching, and then, at the very least, nodding and pint-raising terms, I’d annoyed him in the latter part of the 1990s by going into business with his ex-partner Andrew Groves. No matter. I never thought – not that he’d have cared in the slightest – that he was anything less than the most talented designer of the last fifty years. I still rate the A/W 1996 Alexander McQueen Dante show, staged at Christ Church in London’s Spitalfields, as the most glorious, thrilling and radical moment in contemporary fashion history.

I recently found a collection of my negatives and transparencies from Dante and the nostalgia was intoxicating, so we decided to reproduce a selection here. Fashion in London had seemed so dead and buried until McQueen appeared and got the party going. It was a wild, wild time. And Dante was the wildest.

I remember catching a short clip of Alexander McQueen’s 1993 Nihilism show on MTV. It was the first time I’d encountered his work, and I only saw a few seconds of it, but I knew immediately that it was something very special indeed. I got in touch with him via mutual friends and he invited me to interview him over a drink at his 25th birthday party, at Maison Bertaux in Soho. Lee was enthralling, funny and unassuming: he asked me to turn off my dictaphone to ask me the meaning of the word misogyny and then said something very rude indeed about Colin McDowell. He was still on the dole and living in squalor, but had a wealth of conviction. He preferred to use lesbian models because he thought they’d be opinionated about their self-image, and he was driven by strong political beliefs: “It’s nearly 2000 and we’re still living in Dickensian times,” he said. “I always try to slam ideas in people’s faces. If I get someone like Suzy Menkes in the front row, wearing her f––king Christian Lacroix, I make sure that lady gets pissed on by one of the girls, you know what I mean? These people can make you or break you, and they love you for just a moment. I may be the name on everyone’s lips at the moment, but they can kill you…”

Lee’s birthday party was shortly after his Banshee show at the Café de Paris, which had been thrilling, dark and iconoclastic, a universe away from the usual post-grad retread of Vivienne Westwood that London had grown weary of. It looked like the wardrobe from the best film that Derek Jarman never made. The subsequent shows – The Birds, Highland Rape, The Hunger and It’s a Jungle Out There – had more sense of occasion than anything else during London Fashion Week. The excitement they generated was incredible.

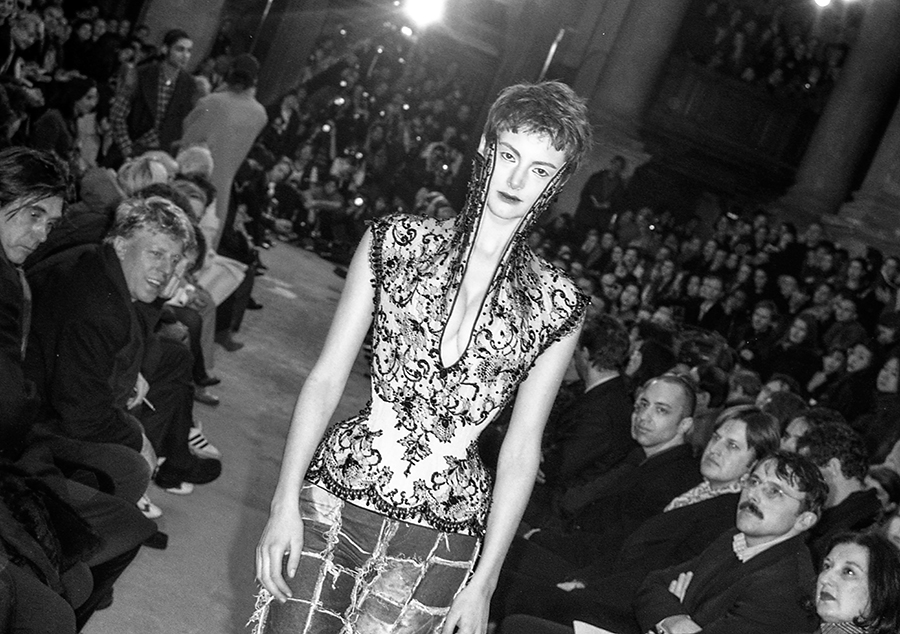

Of all his early London shows, Dante was the really special one. It began with the sinister flicker of lights in the church (McQueen’s muse Issy Blow was enthralled by the idea that Christ Church’s architect Nicholas Hawksmoor had been a Satanist), and then a blast of gunfire and hip-hop. What followed was a half hour of the most extraordinary new shapes and cuts, aggressive but still elegant: chiffon and lace; lavender silk taffeta; white cashmere with black fern prints; horns and huge collars of Mongolian lamb. The tailoring was a revolution in itself and the fabrics were so startlingly rich. There was sculpture and performance art. It was terrifying and exciting. For a small, still relatively underfunded studio to produce such incredible work was one thing, but the coherence and the drama of the story the collection told was something else entirely. As fashion historian Judith Watt recalls, in her definitive book Alexander McQueen The Life and the Legacy: “The links between Dante Alighieri, the Florentine fourteenth-century poet and author of The Divine Comedy were implicit at first, but the strange fusion of the inferno of life with the inevitability of death gradually became obvious.” Alexander McQueen’s Dante was a rare expression of fashion as fine art, right down to its LL Cool J soundtrack.

Honor Fraser on the catwalk, Bryan Ferry and Antony Price in the audience: Dante was the first time that an extreme richness and a finessed couture-like sculptural element had been seen at Alexander McQueen. Lee would be a controversial but inspired choice for Givenchy

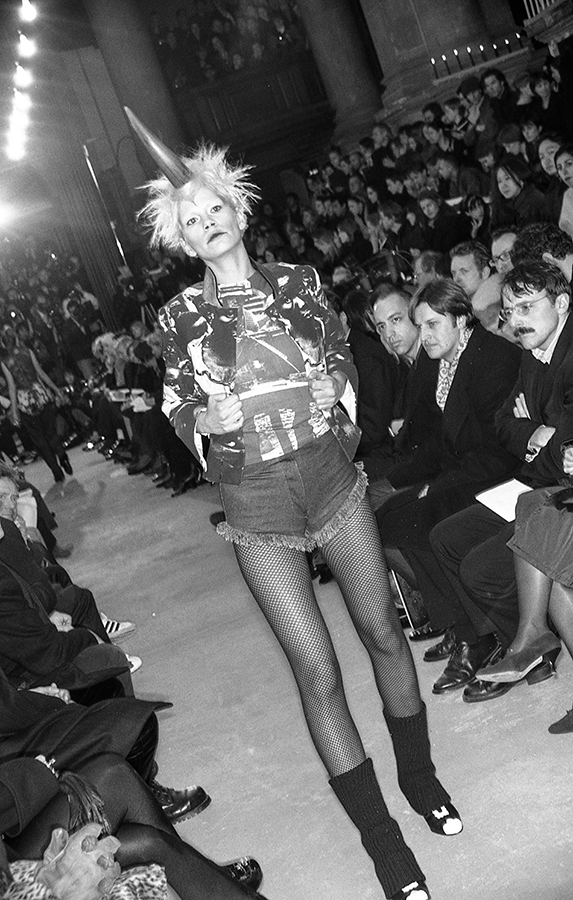

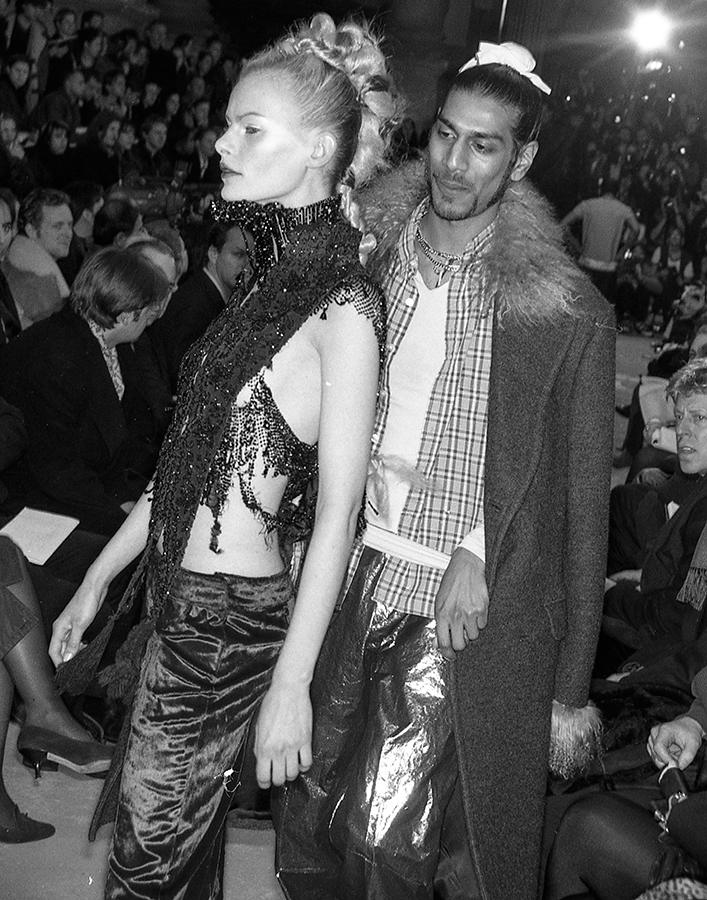

Plum Sykes in black lace and bleach splashed denim with spikes and crucifixion jewellery in the Baroque Christ Church. Sykes had been a friend of McQueen’s since she had been an intern at Vogue. Other models included Kristen McMenamy, Annabel Rothschild and Stella Tennant. Simon Costin contributed some of the art direction elements and the dramatic lighting design was by Simon Chaudoir

Many of the models in Dante were “real” East End kids – a nod to the Brick Lane milieu of Christ Church, with styling reminiscent of the gangs in Warhol acolyte Paul Morrissey’s Mixed Blood. The collection was firmly ensconced in luxury, but it was still infinitely edgier and more in touch with reality and the street than the world of establishment fashion

The prints in McQueen’s Dante were monochrome, disturbing and extraordinary. He asked war photographer Don McCullin for permission to use some of his iconic imagery on garments and was refused. He went ahead and used them anyway

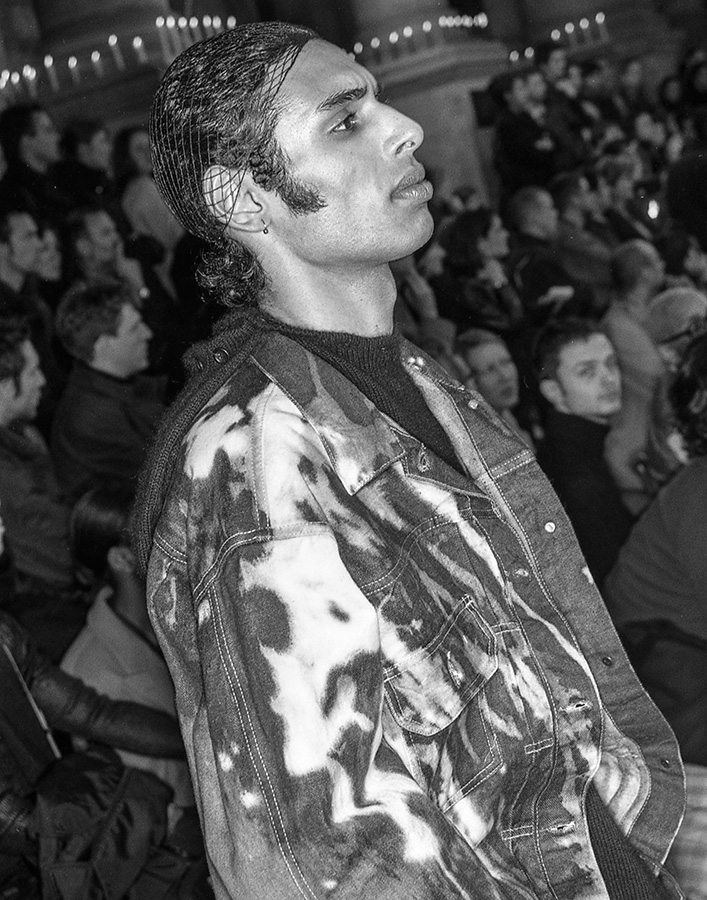

Dante was the first appearance of bleach splashed denim at Alexander McQueen. With its punk and skinhead connotations, it was shorthand for the edgiest, street-focused aspects of his work. It would appear throughout the violent and riotous It’s a Jungle Out There show (A/W 1997) at Borough Market, which nearly ended in disaster when students gatecrashed the venue, knocking over flaming cans of fuel next to cars

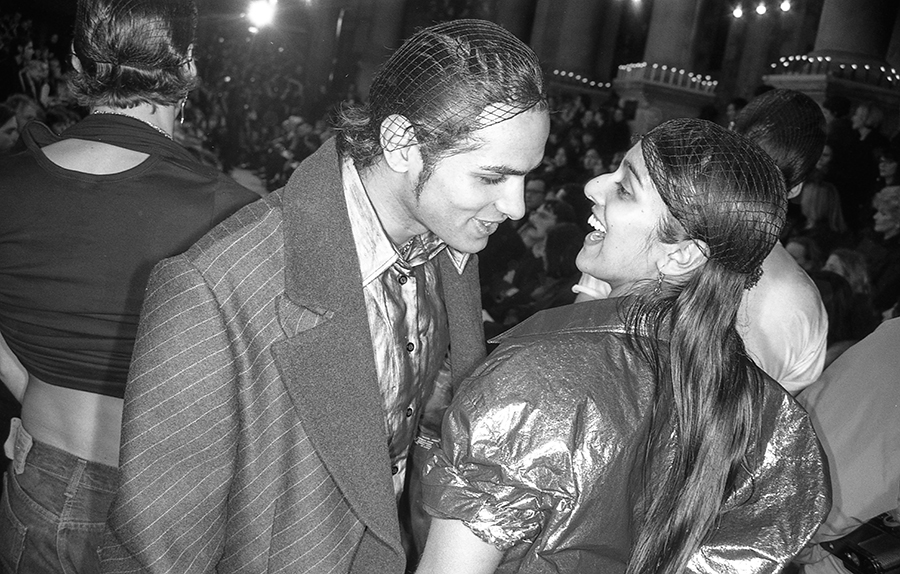

As well as the extraordinary womenswear, McQueen’s menswear as part of Dante was striking. He had debuted bumsters for men and techno fabric suiting as part of The Hunger one season before, but the severely shaped blazers with double lapels and pinstripes and plush overcoats from this collection – which Lee wore constantly himself around Soho, complete with crucifix – were stunning

The masks in Dante were a homage to identical pieces that appear in the photographer Joel-Peter Witkin's work. Witkin's often nightmarish imagery is created using cadavers. McQueen would go on to create a very literal Witkin tableau in his later, S/S 2001 show Voss, featuring the writer Michelle Olley naked and masked on a chaise longue, replicating the focal point of Witkin's 1983 artwork Sanitarium