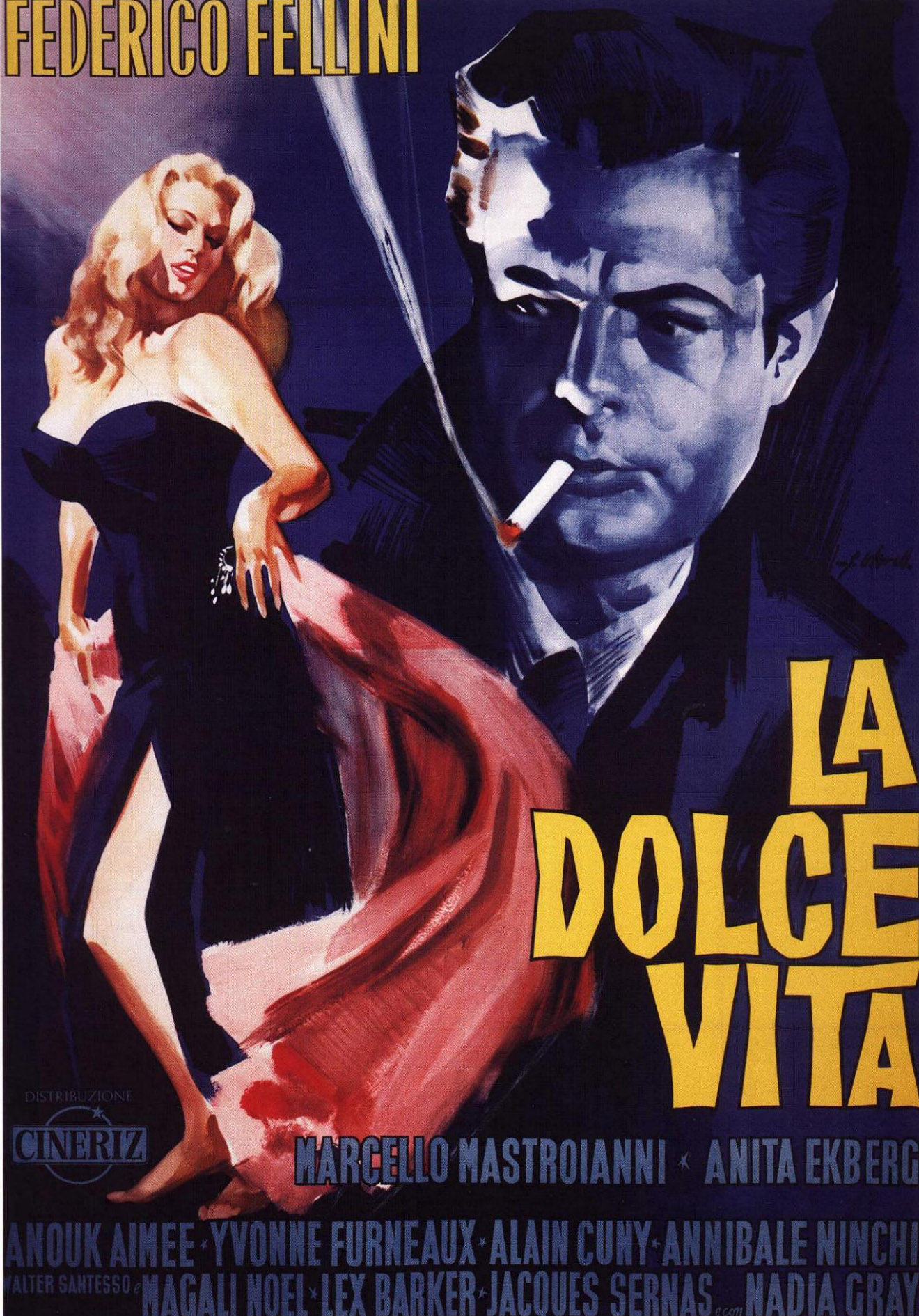

La Dolce Vita (1960)

With La Dolce Vita, Fellini regenerated a corner of post-war Europe into the most stylish of destinations, and created the grandest of cinematic myths. His depiction of cool Italian tailoring, cappuccinos, sunglasses and Vespas went on to influence the Soho Mods and many a moped-riding congestion charge dodger. After the austerity of fascism and rationing, La Dolce Vita was sexy, glamorous and magnificent.

The good life has been associated with Rome since ancient times. The Emperors, Pontiffs and influential families that have adorned Rome’s history are well known for their licentious corpulence and love of “the sweet life”. Fellini chose the title for his 1960 film ironically, to expose the underbelly of society, repeatedly showing religious icons and rituals as meaningless to the modern Romans.

The seven hills of Rome are used to reflect the seven deadly sins as the cynical columnist Marcello Rubini pursues his scoops among the cafés of the Via Veneto, cluttered with the city’s aspiring glitterati. Rome was always seen as a place of culture and history, but it was La Dolce Vita that made it romantic. Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain is one of the most iconic images of the 20th century.

The film’s international reputation and influence could not have been predicted. The city and its monuments became synonymous with the film stars. The turtleneck sweater look became known as a “dolce vita”, “Felliniesque” became a commonplace term and the “paparazzo” – the word originally meaning “gnat” – came into being. The theme of an empty society driven by fame for fame’s sake make the film far more of a prophecy than was realised at the time.

In a way, it sums up the real Rome that is so incomprehensibly wonderful: the awful driving, the political corruption, the postal system that just doesn’t work.

La Dolce Vita was a cause célèbre that enjoyed considerable critical success, despite the fact that the Catholic Church gave it a cinema rating that equated watching the film with committing a sin. But the success of the film also heralded the end of the Via Veneto’s popularity with movie stars and the international rich: as the tourists flocked, the celebrities fled.

In reality the film’s Via Veneto was built on Cinecitta’s number five sound stage. The street was exact, down to the smallest detail, but it had one thing peculiar to it: it was flat instead of sloping. “As I worked on it, I got so used to this perspective that my annoyance with the real Via Veneto grew even greater,” said Fellini. “Now, I think, it will never disappear.” In a way, it sums up the real Rome that is so incomprehensibly wonderful: the awful driving, the political corruption, the postal system that just doesn’t work. There’s a mad woman who feeds the strays cats in the Colosseum and the Fontana di Trevi is, of course, a tourist-mobbed water feature at the end of a scruffy street. But you still go because it’s Rome, it was once the centre of civilisation, and because La Dolce Vita made you love it.

When Marcello Mastroianni, who played the lead character in Fellini’s film, died in 1996, the city turned the Trevi Fountain off and draped it in black. “There is a sort of suspended air about things in this city,” said Fellini, “and it is this atmosphere that makes one say ‘coming to Rome means being reborn’.” His complex cinematic portrait gave new life – somewhat accidentally – to the most ancient of cities in way that has never been equalled in the arts.