Pasolini’s last supper

Mark C. O’Flaherty on the murder of Pier Paolo Pasolini, carbonara, and the rarest, realest, bloodiest of steaks in Rome

Mark C. O’Flaherty on the murder of Pier Paolo Pasolini, carbonara, and the rarest, realest, bloodiest of steaks in Rome

I’ve been binge watching Pasolini recently, inspired by the director’s centenary last year. Celebrating the birth date of the dead is a weird thing to do. “Happy birthday, Boudica! Many happy returns, Hitler!” That’s not how it works, is it? There’s no cake, no candles. But I understand the marketing value. I’ve also been spending a lot of time in Italy of late, after realising that splitting time between London and New York was no longer sparking joy. Italy is the anti-New York. It’s full of beauty, the food won’t poison you, and people live in apartments blessed with natural daylight and enough space to swing substantial dead felines.

Did Pasolini, sceptics ask, really drive 40 minutes out of town for sex with a trick he’d already picked up and had next to him?

Like any big city, Rome has its sketchy neighbourhoods, but its history is centuries richer than Manhattan’s. While the downtown of the latter has the legacy of the Beats, Warhol, the Mudd Club et al, Rome has Pasolini. Who trumps all of the above. This is where his productions were based, and where, of course, he was brutally murdered – leaving a body so mutilated it was barely identifiable. It’s where his myth was created. On a recent sweltering evening I retraced the steps of his final hours, from his last dinner to where he met his demise in the scrublands by the coast at Ostia.

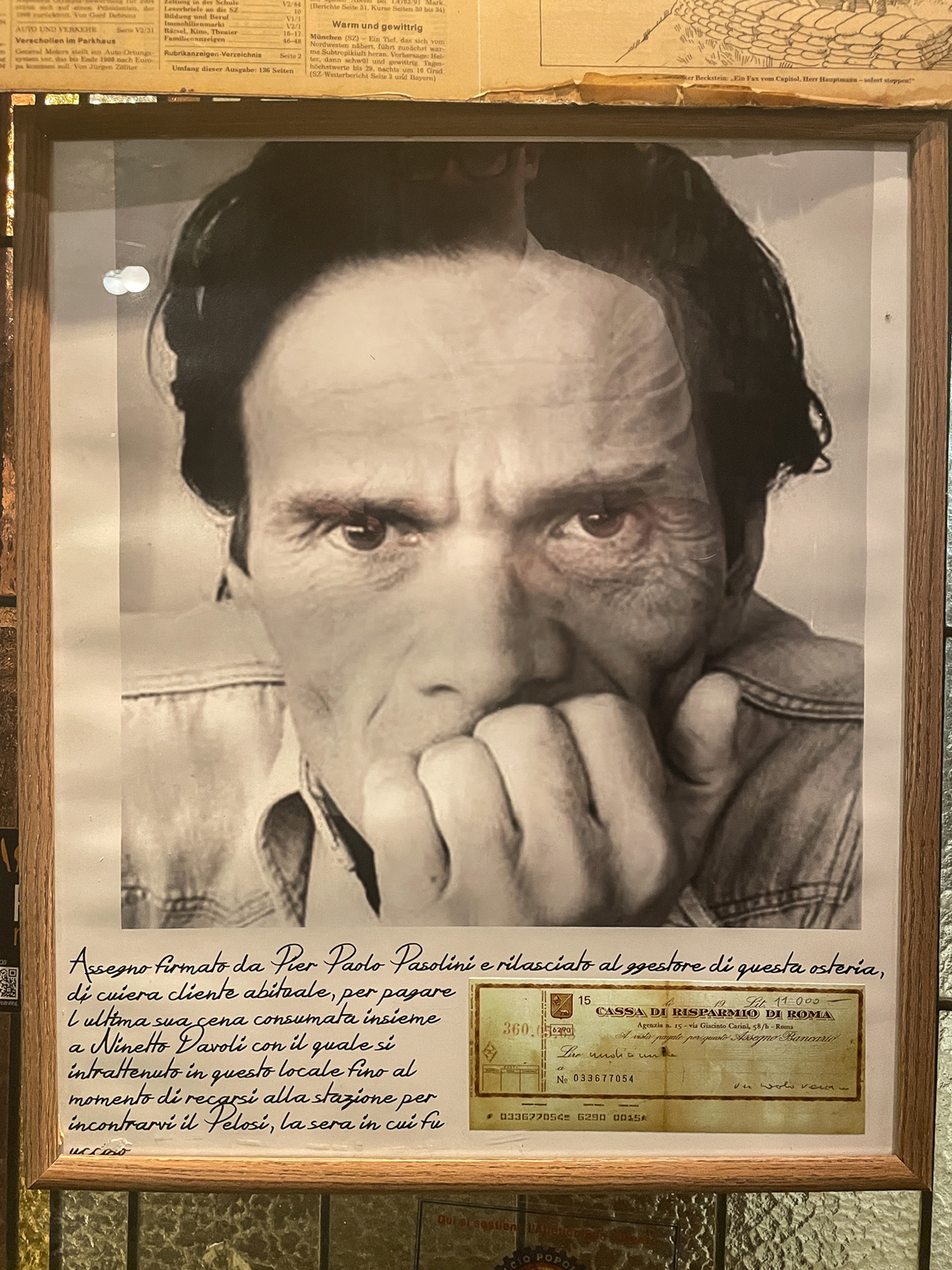

Pasolini’s uncashed cheque at Pommidoro

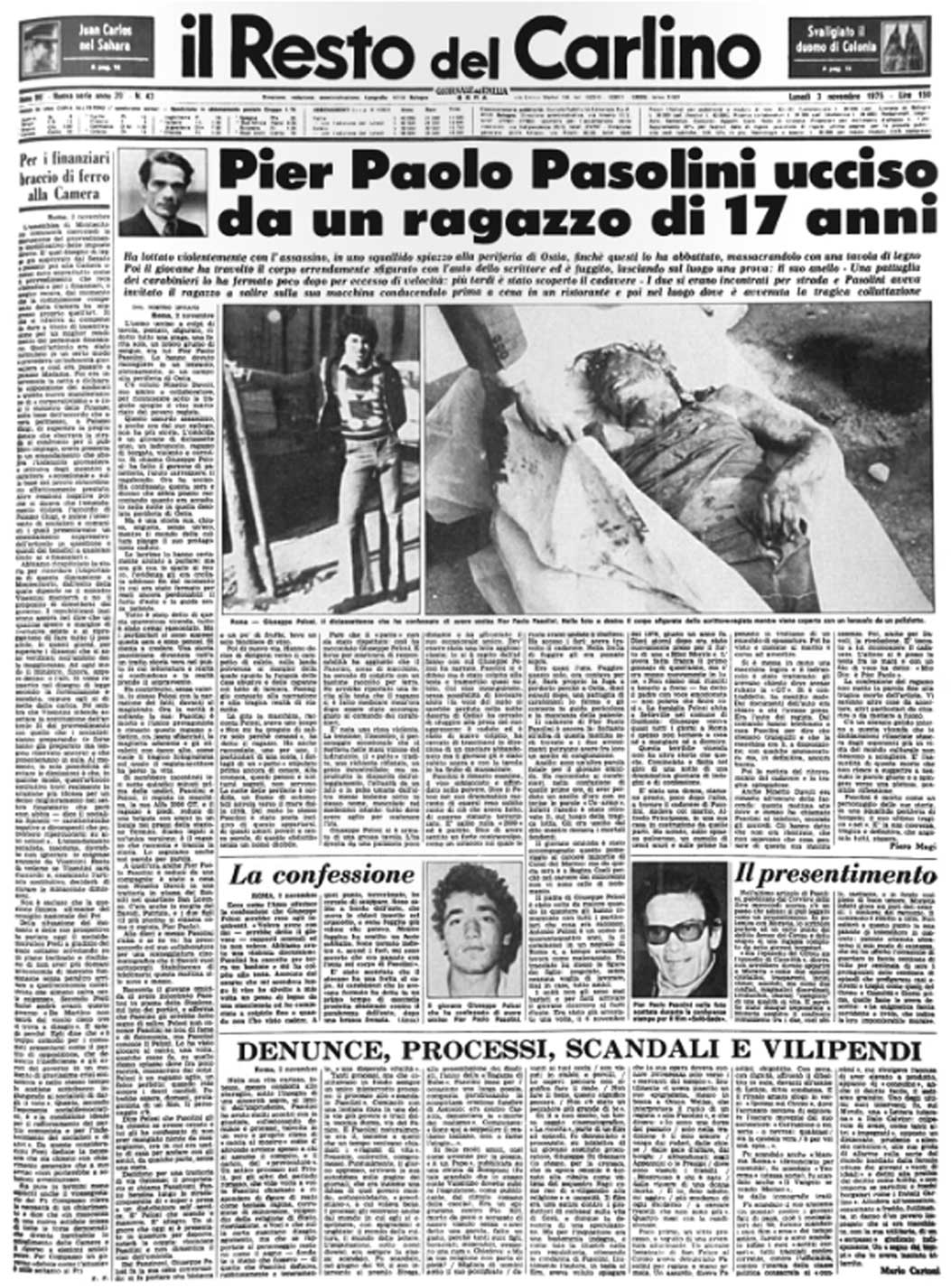

There’s an ongoing debate about what actually happened that night in November 1975. We know that he had upset powerful people by throwing a spotlight on the complex conspiracy surrounding the death in 1962 of Enrico Mattei, head of energy company ENI, in a “mysterious” plane crash. He had also written damning columns in the newspaper Corriere della Sera, calling for the Christian Democratic party to face prosecution for its ties to the mafia. There was also the issue of the bizarre theft of reels from Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom, the masterpiece (pictured top) whose edit he was finishing at the time of his death.

Pommidoro

The version of events documented by the prosecution and legal system seems straightforward: Pasolini had dinner with his former lover, actor Ninetto Davoli, at Pommidoro in San Lorenzo, then went cruising for rough trade at Roma Termini. “The arcades of the station are like a temple of Eros that casts an aura around the rituals of arrivals and departure,” writes Enzo Siciliano in his biography of the filmmaker. Pasolini, according to this account, picked up 17-year-old rent boy Giuseppe Pelosi, and they headed southwest from the city in Pasolini’s car, stopping at Al Bionde Tevere for a nightcap (and a plate of pasta for Pelosi). Then they continued on to the coast at Ostia. Here is where things went, according to the official version, south.

Mark C. O’Flaherty at Pasolini’s table at Pommidoro

In his initial confession, Pelosi claimed that Pasolini wanted to anally penetrate him with a stick; not unreasonably, the boy refused and a fight broke out. Pelosi battered Pier Paolo unconscious, then murdered him by driving over the director with his own Alfa Romeo. Pelosi retracted the confession years later in prison and it’s long been agreed by detectives that there were several people present at the scene. Accordingly, in March 2023, film director David Grieco and screenwriter Giovanni Giovannetti petitioned to have the case reopened, and three pieces of previously unidentified DNA evidence examined. Did Pasolini, sceptics ask, really drive 40 minutes out of town for sex with a trick he’d already picked up and had next to him? Was he out there because he was promised the return of the stolen reels of Salò? Or was there a weirder angle to it all? Kathy Acker’s “novel”, My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini, takes the view that it was a suicide of sorts – that Pier Paolo engineered the incident knowingly. And she’s not alone in the theory. It’s frequently bandied about in art circles. Being battered to death by a teenage urchin he’d hooked up with transactionally would certainly have been on brand for the filmmaker. As an exit from public life, it couldn’t have got more attention. It could have been a kind of perverse performance art.

So much to ponder. So little chance the truth will ever be established.

A front page on 3rd November, 1975

But Pommidoro remains. The walls are covered in memorabilia, including the uncashed cheque written out in payment for his dinner with Davoli. I’m reminded of Geoff Dyer’s would-be biography of D.H. Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage, in which he recounts his visits to places Lawrence lived and worked and his own thwarted efforts to feel a feeling, a resonance, in those locations. Did I feel a feeling at Pommidoro? Yes, I did. The thing about Italian restaurants is that they rarely change: they don’t redecorate, and they never dim the lights – the scene is always as blindingly bright as a traffic accident. I sat at Pasolini’s regular table, and it could have been 1975.

During dinner I spoke to Aldo, the youngest member of the Clementinas to be involved in Pommidoro, representing the fifth generation of the family-run business. His mother Alessandra was also present – and she’d been there, too, aged 14, on the night Pasolini had his last dinner. “I remember there was something wrong,” she recalls. “He was anxious. He hugged my father and told him he should leave Italy. They had been close friends for years. My father had first met Pasolini when he was being hassled and bullied outside on the street. He went out and rescued him. He was a regular in the restaurant after that.”

There’s something uniquely Italian and contradictory about how revered Pasolini remains in his country. He was a Catholic Communist, with an obsession with barely legal and underage boys, evident in so much of his work: the camera lingers over luminescent pubescent male skin until it makes the gaze restless and uneasy. Salò is difficult to watch because there’s a kind of Dennis Cooper element to the early scenes, where the POV makes you complicit in enjoying the domination and physical manipulation of the captive boys and girls. From then on, you have to work out where you’re bailing on that problematic dynamic. By the time they’re all eating shit at a wedding banquet, you’re definitely pulling the rip cord.

As for Pommidoro itself, it’s all about the carbonara and olive oil. The family have been harvesting their own brand oil for decades. You can buy it to take away and it’s great. The carbonara is also superb, albeit unusual: the guanciale is cut typically Roman style, in lardon-shaped chunks, and the dusty rather than freshly ground black pepper that dominates the plate makes it closer to cacio e pepe than most carbonara. When I went recently, I ordered a fillet steak as a secondo. Rare I asked for, rare it came. The aroma was overwhelming, and it bled profusely as I cut into it. I was dining with my husband who asked if I could please eat it as quickly as possible, because it was just too … real. I empathised, and devoured it fast, deciding to pivot to vegetarian dishes for at least week. There’s something about blood pooling around your dinner that makes you think it’s not quite what you should be eating. But then, at Pommidoro, it felt apposite. May it never close. May Pasolini never be forgotten. C