Scratching the surface

Independent and underground cinema is, says Mark C. O’Flaherty, a dream palace for the rediscovery of the lost landscapes of London and New York City

Independent and underground cinema is, says Mark C. O’Flaherty, a dream palace for the rediscovery of the lost landscapes of London and New York City

As I write this, in the midst of a sarcastically radiant spring, the London and New York that I know have vanished. Both are in lockdown. Life is on pause. We have – temporarily at least – stopped defining ourselves by how we engage with stuff outside, and turned banal domesticity into light entertainment on social media. We’re also reading a lot, and drinking our way through movie marathons. Like seeing people light up cigarettes in restaurants and bars in TV from the 20th century, “normal life” suddenly looks strange bounced back at us as fiction. The street doesn’t exist as it did. Cinema has always been nothing if not a transmission from the past. And while our cities feel alien to us right now, we’re familiar with them already, from years of dystopian sci-fi. We live in Gilead, Westworld, 28 Days Later. But there are other places and other cities.

1979 – a time when the most cinematic of cities had devolved into a bankrupt, Hieronymous-Bosch-with-hot-dog-stands vision of hell

One of the best purchases I have made in recent years has been a home cinema projector. With a single HD stroke my lounge looked like someone far more cerebral than me lived there (all those books and no TV set!). At the same time, watching a film at home became an event: you can’t really channel-surf with a projector and a wall-sized image – rather like walking down a hospital corridor with a gauntlet of open doors, you’re never sure what you might catch a glimpse of. I have now become accustomed to fastidious scheduling and programming – during the first week of lockdown, it was a Peter Greenaway season. Tarkovsky is up next. Apart from Doctor Who, I haven’t watched terrestrial TV once since I upgraded my home tech. I’m that millennial.

Ms.45 by Abel Ferrara

One of my most surprising cinematic discoveries of late is just how good Abel Ferrara’s canon is. He is the ultimate urban auteur. I first encountered him when I was barely a teenager with Driller Killer, which I watched on one of the rental VHS cassettes that had been sequestered discreetly and illegally behind the counter at my local video shop in Penge. Tabloid furore meant we could no longer select our entertainment from shelves lined with lurid covers and outsider-art interpretations of Tom Savini’s grand guignol SFX. Instead we had to ask for “the special list” and pick them based on what we’d memorised from Fangoria magazine. Now, I didn’t much like Driller Killer at the time: unlike the other slasher, cannibal and zombie movies I enjoyed with my school friends after afternoons at Kensington Market it felt genuinely… unpleasant. It was grubby. It was sordid. But it is Ferrera’s vision of New York to a tee, and it perfectly sums up 1979 – a time when the most cinematic of cities had devolved into a bankrupt, Hieronymous-Bosch-with-hot-dog-stands vision of hell.

Jubilee by Derek Jarman

Independent and underground cinema, from Ferrara to Jarman, from the 1970s to the 1990s, has created a solid gold archive of New York and London rarely captured anywhere else. It’s a twisted joy to dip into, particularly now. While Ferrara was making Driller Killer, Woody Allen was lensing Manhattan – a radiant love letter to his hometown. The two inhabit the same island but not the same universe. And what Ferrara didn’t finish with his power drill in 1979, he continued with Ms. 45 in 1981 and nailed with Bad Lieutenant in 1992. The city looks fabulously degenerate and dangerous in all three, everything so dramatically different from the New York of today, from the shoes on an incidental passer-by to the adverts on buses and colours of the street signs.

Hail the New Puritan by Charles Atlas

Apart from Ferrara’s visual flair – which looked borderline inept back in the day but now seems uncompromising, refreshing and raw – it’s his authenticity that makes his particular time capsule so fascinating. His key collaborator was Zoe Lund, who played the lead in Ms. 45 (a mute Fashion District seamstress turned gun-toting rape revenge heroine clad in a nun’s habit) and also appeared in, and wrote, Bad Lieutenant. You don’t get to make films like Ferrara unless you immerse yourself in the right wrong company, and in real life Lund made Edie Sedgwick look like Taylor Swift: a raging smack addict and profoundly bohemian fixture of the downtown scene, her very existence today in NYC would be an anachronism.

Midnight Cowboy by John Schlesinger

When filmmaker Charles Atlas – renowned for his work with New York dance legend Merce Cunningham – collaborated with Michael Clark on Hail the New Puritan in London in 1985, it wasn’t just an inspired day-in-the-life docufantasy about the Scottish dance star, but a disco passeggiata through the streets, clubs and squats of the time, a madcap punk ballet that also captured one of the most creative periods in British subculture. Along with John Maybury’s short films in collaboration with the BodyMap fashion circus, it now feels beamed from a parallel universe, one where anything was possible.

This isn’t the Richard Curtis school of cinema where every setting has to be UNESCO-worthy and laboured over

Atlas’s work shares a lot with the cinema of Derek Jarman, most notably Jubilee, which made use of the tremendous, abandoned Butler’s Wharf loft that Jarman was living in for much of the 1970s. Today, of course, the area is defined by waterside Pizza Express regeneration and two-bedroom flats that sell for £3mn. Where would you find a square metre of abandoned urban space in the heart of London now? Circa Jubilee, every other street corner in East London looked like the Luftwaffe had flown over five minutes before. I always wonder what didn’t make the cut in films like this. I love all of Jarman’s Super 8 work, and it always feels like he was great at getting it seen in a myriad formats, from ICA happenings to Smiths promos. But then there’s Ron Peck, best known for his seminal gay work Nighthawks, whose 1991 boxing documentary Fighters involved shooting over 100 hours’ worth of footage of East London. That archive must be a treasure trove of lost London, fascinating to delve into.

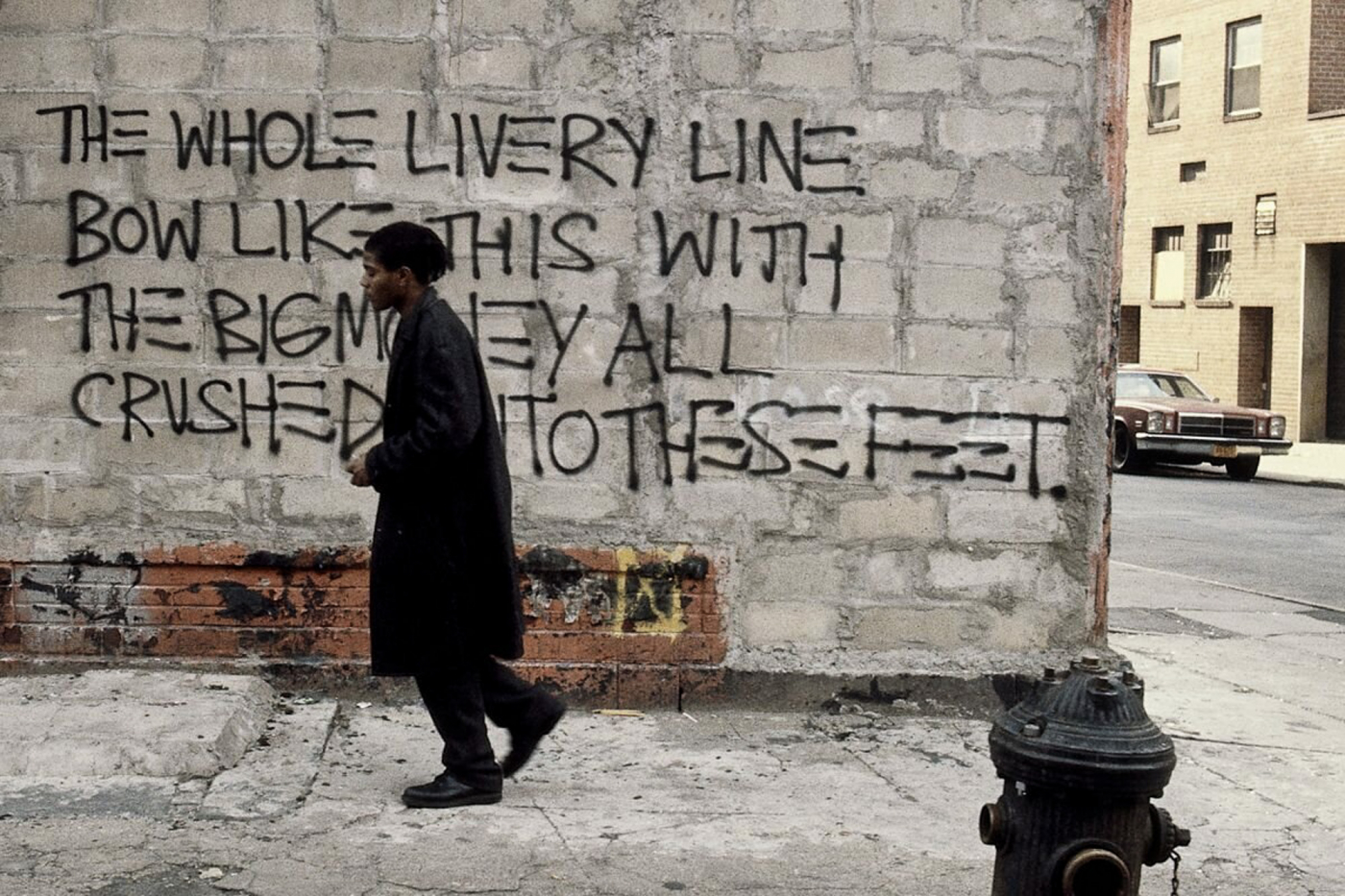

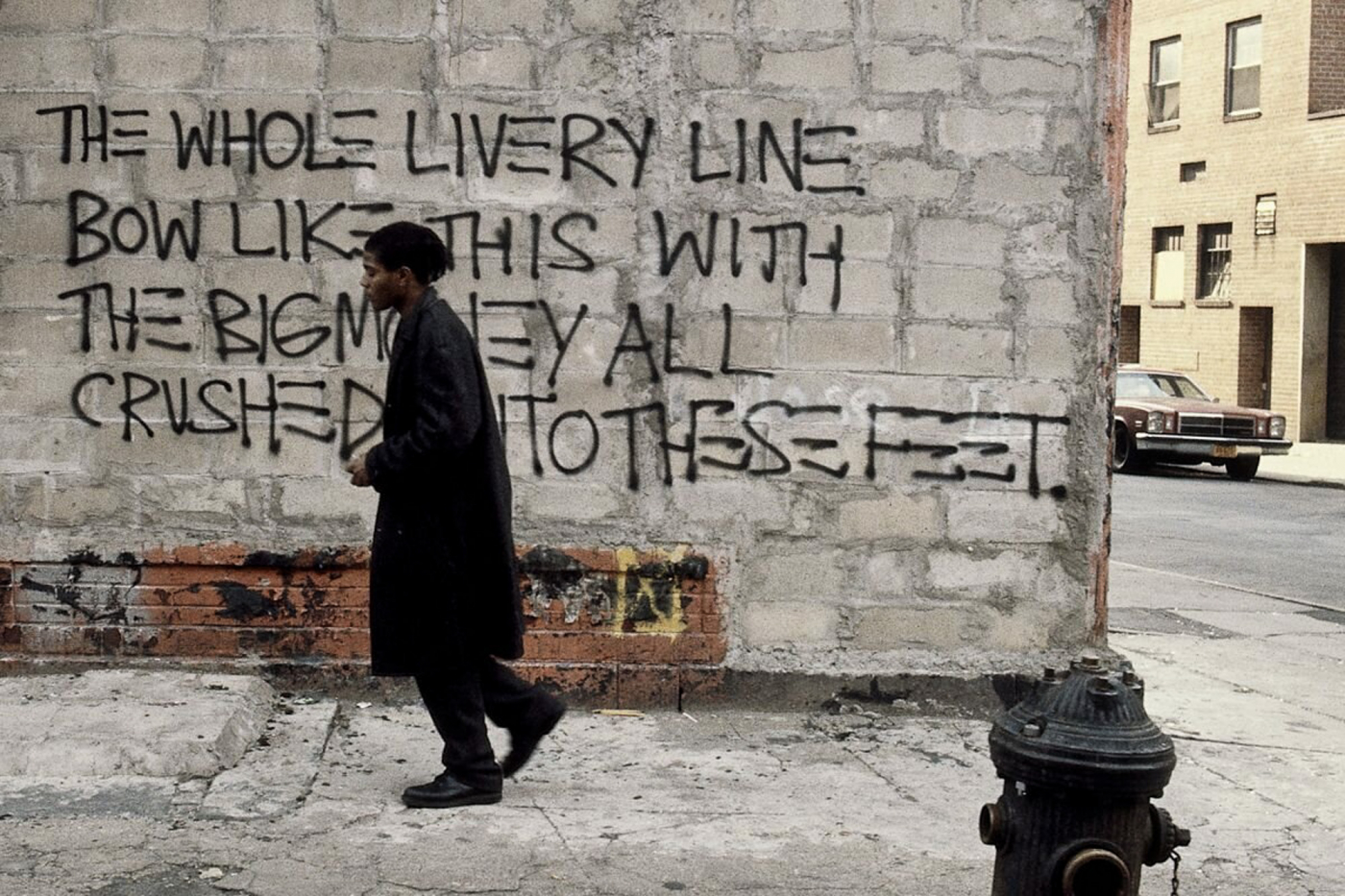

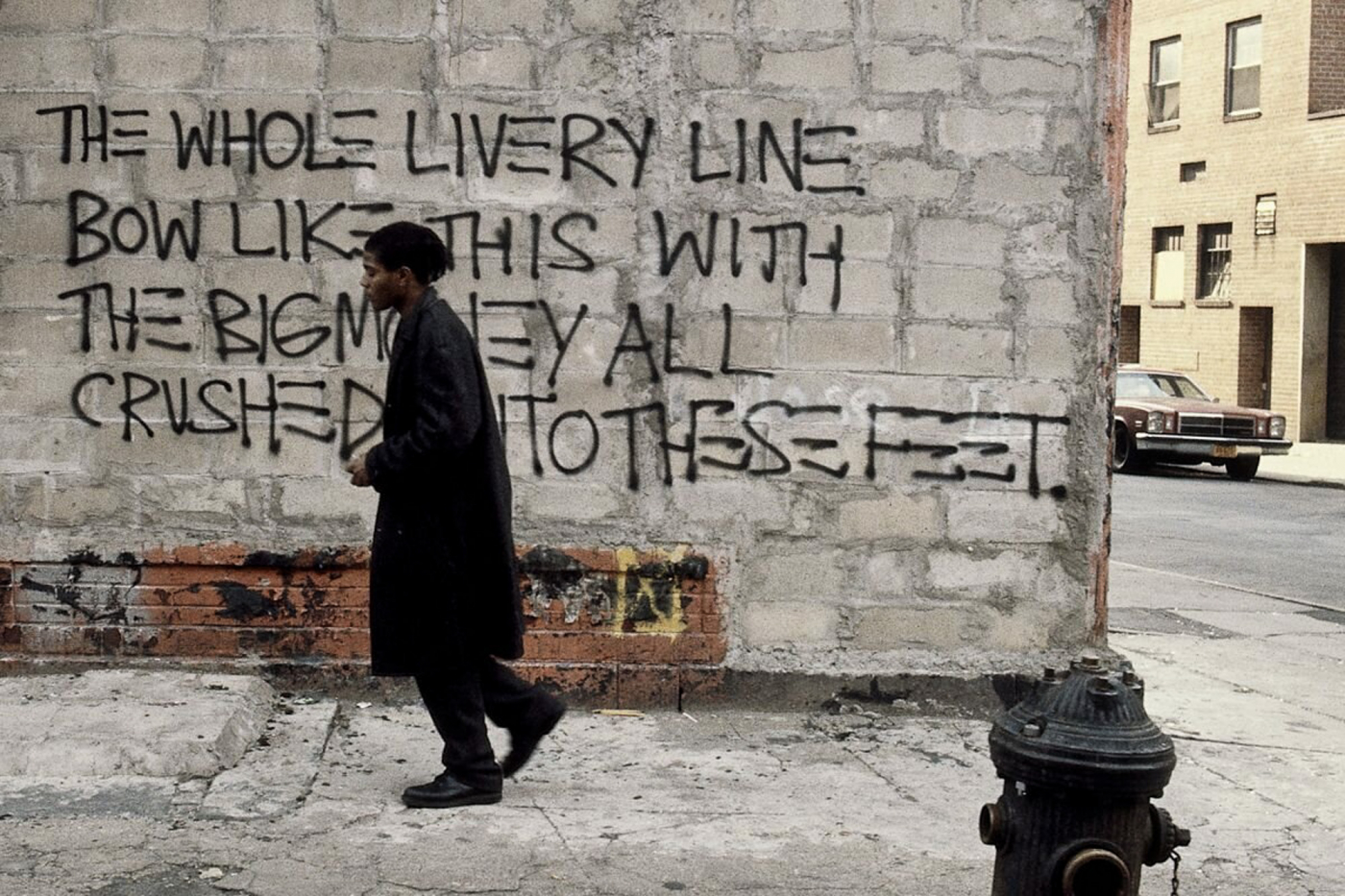

Downtown 81 by Edo Bertoglio

The joy of underground cinema is that it casts its light on things that felt incidental at the time: a pub, corner shop, greasy spoon or the sidewalks that served as the milieu for every Cassavetes movie. Even Robert Frank’s 1972 film FOOD, about artist Gordon Matta Clark’s SoHo conceptual restaurant of the same name, feels matter-of-fact about its subject, which today makes it all the more compelling. This isn’t the Richard Curtis school of cinema where every setting has to be UNESCO-worthy and laboured over. It was point and shoot. When Glenn O’Brien wrote Downtown 81, a barely-fictionalised movie about the comings and goings of a Basquiat-like character, played by Basquiat himself, the most interesting character of the movie was degenerate New York itself. Along with Susan Seidelman’s Smithereens, which came a year later in 1982, it depicts an East Village unrecognisable from the $15 cocktails and designer consignment stores of today. Likewise Charlie Ahearn’s Wild Style, which was the most authentic depiction of the rise of hip hop culture in the Bronx and the Lower East Side… I went to an opening of Lee Quiñones artwork a couple of years ago down on the LES, and didn’t realise until I got there just who he was – here was the star artist from Wild Style, back in context, three decades on. Squint, and the streets around Chinatown still look as they did in Wild Style – the Lower East Side still loves graffiti. But you do have to squint – a lot.

Wild Style by Charlie Ahearn

A lot of the allure of independent cinema is in the glamour of the scenes it documents. Perhaps Paul Morrissey’s work with the Warhol set is the most obvious. But at the time Morrissey and his ilk were most active, the distinction between underground and mainstream cinema and culture was far less marked than it would become once Star Wars arrived to turn cinema on its head. In visuals and attitude, most of Scorsese’s early work set in New York uses the vernacular of the underground; ditto John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy, which came out in 1969, and features Warhol stalwarts Viva, Ultra Violet and Taylor Mead, and Morrissey himself, in bit parts. It’s a film that captured Times Square at its most fragrant, from its extravagant and kitsch advertising installations to the beyond seedy sex cinemas of 42nd Street.

It’s not just that New York and London look so different today. Or didn’t, until March 2020. They behave differently as well. Which isn’t to say that there isn’t interesting working being made, and interesting people making it; it’s just different. We live in compelling, weird times. And who knows what new cinema will tell us about our cities in 30 and 40 years’ time? One thing is certain: They don’t make them like they used to. C