What’s on your top ten movies list? Thelma & Louise maybe? You know the one – two women go on a road-trip to find freedom, end up on the run from the police after one of them is sexually assaulted by a stranger, then have to drive off a cliff and die because they were all uppity and didn’t know their place in life. Maybe you’re partial to Fatal Attraction, in which Glenn Close’s Alex is put through the wringer by an adulterous scumbag, has a mental breakdown, and then gets shot dead before she can cause any more inconvenience to him and his cosy little nuclear family. These examples aside, I probably don’t need to tell you that American cinema has a problem with women.

I probably don’t need to tell you that American cinema has a problem with women

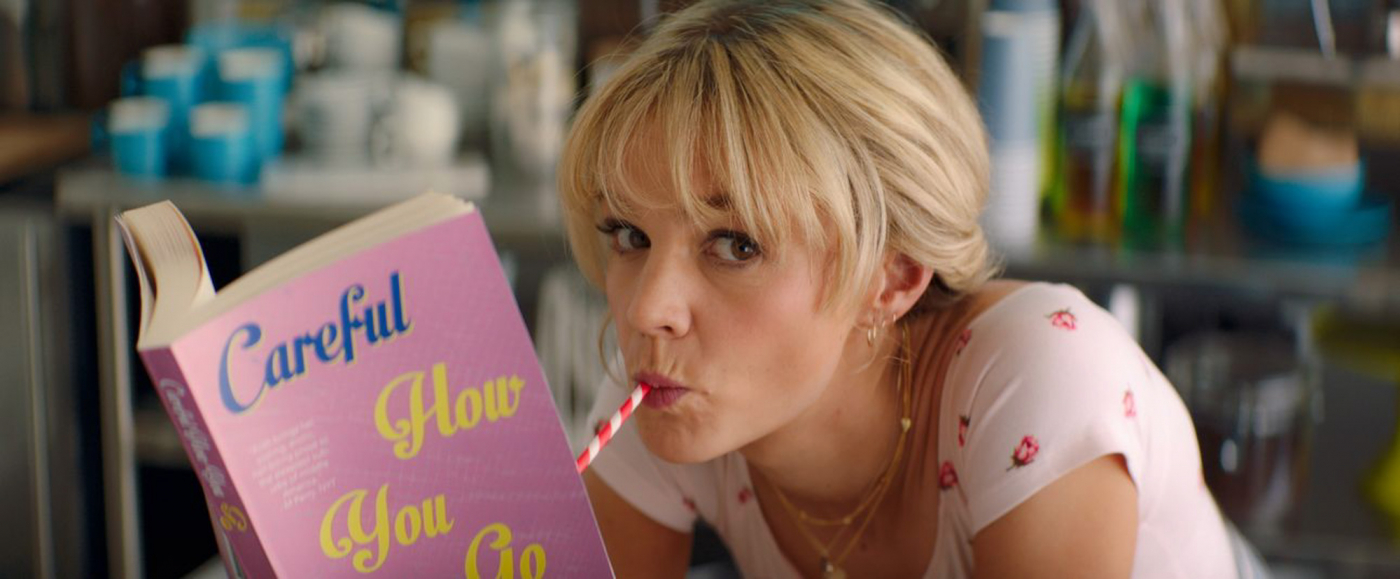

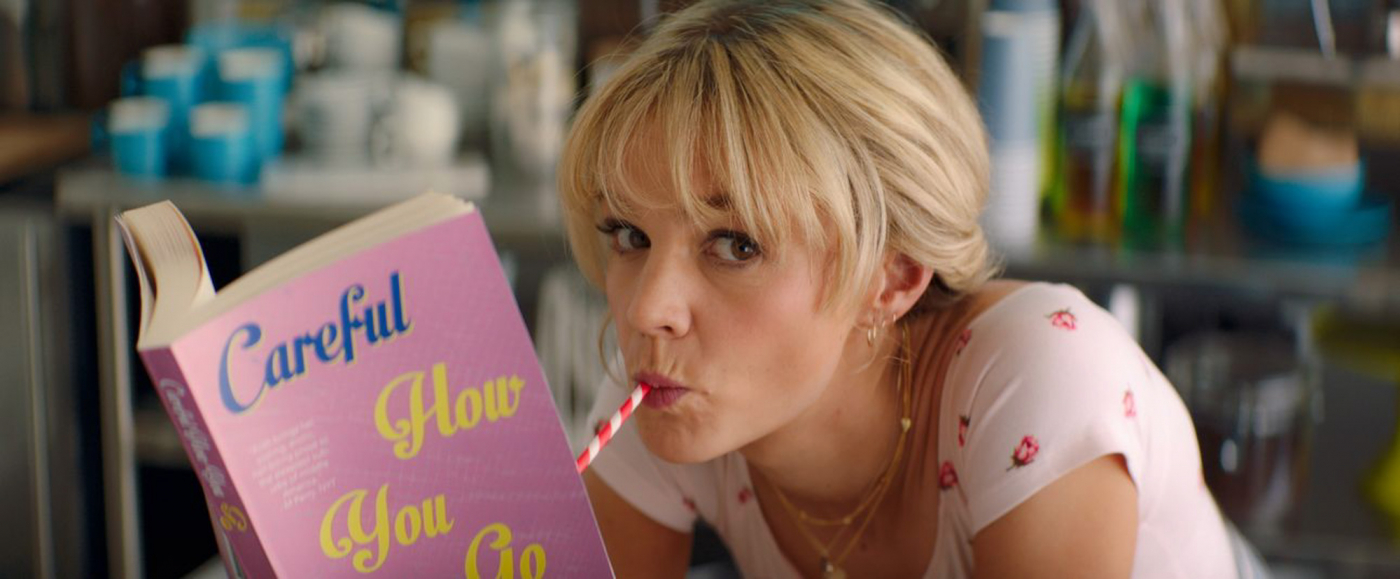

One of the films nominated for this year’s Best Picture Oscar is Promising Young Woman, written and directed by Emerald Fennell (who makes a cameo offering a “blow job lips” video tutorial). It has a lot of style, and plays with genres with elan. It looks like a classic teen comedy – all California pop colours and Charli XCX – but it’s a genre movie of a darker kind: rape revenge. It would make an interesting double bill with Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45, in which a mute seamstress goes on a killing spree after being raped twice in one day. The consensus the films share is “yes, all men”. But there are huge differences – Ferrara’s character, Thana, becomes a cold-blooded killer. She dies at the end, but her moral compass has spun so far around that there’s not really a way out for her. No matter, she spends most of the film as a fabulous force of nature, and you root for her. In Promising Young Woman, we find Carey Mulligan’s Cassie suffering trauma after her closest friend, Nina, was raped at college some years before, taking her own life after the event. The rapist, while known to all, suffers no immediate consequences. So far, so depressingly real. Cassie spends her evenings donning heels and posing as drunk and vulnerable in bars, baiting potential predators, then turning on them. She is offering a valiant public service. But for anything particularly hands-on, she pays men to be her accomplice.

c/o Focus Features

It’s a film about surprises and “gotcha!” moments, including the discovery that the one man from her peer group who might be worth caring about (and thus offering her the chance of a “normal life”) is as tainted as all the rest. Yes, all men. But, but, but… And this is the big spoiler – as we reach the final act, Cassie gets killed while exacting her ultimate revenge. Off the cliff she must drive…

There’s much to applaud in Promising Young Woman as a feminist discourse. We can’t talk about consent enough right now. If the only thing Michela Coel ever created in her career was I May Destroy You, it would still make her one of the most important writers of her generation. I had a conversation with a (gay male) friend about the gay rape scene in Coel’s show, and was horrified that he considered it unremarkable – as consensual sex had taken place already, the non-consensual sex that followed was just gravy. We still have SO MUCH to talk about. All of us.

Consent is the theme of Promising Young Woman, but it’s also about what it means to be a woman in the 2020s, and where women stand in society, at a time when a thankfully dying breed of throwback feminists can’t get on board with the essential truth that transwomen are women, and believe that “sex change surgery is unnecessary mutilation”. To have Laverne Cox playing the owner of the café who just happens to be a woman, not a transwoman, is truly refreshing. Hurrah for this.

c/o Focus Features

The film that Promising Young Woman brought most to my mind was Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, starring Isabelle Huppert. Elle is genuinely shocking and a real original. It is also unimaginable in American cinema. Rape comedies really aren’t really a genre, and Elle is wickedly genre-defying. Mark Kermode described it perfectly in The Guardian: “less a thriller than a (Bechdel test-passing) character study; a ‘mystery’ in which the identity of the assailant is hardly hidden”. It’s complex and clever, outrageous and challenging. Huppert’s Michèle is powerful throughout, and the ending walks a fine line on issues of consent and guilt. Huppert displays the same bulletproof energy as Frances McDormand in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri; by the end, you yearn for more scenes in her company.

In Promising Young Woman, Cassie has been emptied out over seven years by grief, and exists purely as a vessel for vengeance. She is all agency, with little potential. She takes pleasure in next to nothing. We are supposed to feel that the posthumous events she puts in place to disrupt a rapist’s life are enough. But they are not. Because by the end of the film two women have lost their lives, and I’d venture the worst the rapist will face is a ruined wedding. But this is a film written and directed by a woman – so one can only assume all of this was discussed in detail. Is it to underscore the nihilism of the whole thing? Perhaps. There’s every chance this is exactly how things would play out in real life. Shit happens.

Back in 1978, when I Spit on Your Grave was released, the rape revenge movie was straightforward

Back in 1978, when I Spit on Your Grave was released, the rape revenge movie was straightforward: you get sexually assaulted by five guys, go to church to give God a head’s up that you’re going to need a significant amount of forgiveness in the near future, then go on a killing spree. Except of course the problem with that format is that if you turn it off after the hour-long gang rape, then all you’ve watched is the worst kind of violent, misogynist pornography. Even if you keep watching, you’ve still watched it. The Catholic-endorsed revenge element becomes abstract – roleplay, in a way, and that’s deeply problematic. But at least the victim lives, and everyone else dies. So there’s that. In Promising Young Woman, there is – thankfully – absolutely nothing to inadvertently titillate. Fennell doesn’t use visual horror to make us feel Cassie’s trauma, yet it lingers over everything.

c/o Focus Features

We live in a time when to see strong women on screen is immensely satisfying, because we live in a world in which women are intimidated as a matter of course on the street every second of every day. 510,000 women were sexually assaulted in the UK last year (and 138,000 men). I can’t get enough of Three Billboards, because I want to will Frances McDormand’s character into real life, in a Purple Rose of Cairo moment. Looking back, so many films I loved on original release now present difficulties. I have seen Soap Dish more times than I can remember, but on my most recent reviewing of it, I realised its casual transphobia. The Breakfast Club ends with Ally Sheedy’s character being schooled by Molly Ringwald’s: Subsume your individuality to be popular and happy as a woman. More recently, Amy Schumer’s issues, wildness and appeal were all given an offensively implausible U-turn by Judd Apatow in Trainwreck. Oh, and then there’s every James Bond film, ever.

Maybe that’s the rape-com trope. The ultimate hope, of course, is that this film soon feels entirely dated in every way

Will Promising Young Woman feel different in just a few years’ time? It has a lot to say, and we all need to talk about it. It’s an important film. I just wanted Cassie, and every Cassie out there, to survive. In slasher movies, the malevolent male is seemingly immortal because… sequels. When a woman seeks retribution through anything other than official channels, she’s toast. Doesn’t Cassie deserve a sequel? Perhaps that’s Fennell’s point: Maybe Cassie’s ultimate sacrifice fits into the reality that men generally get away with it and women don’t. Maybe we’re meant to feel frustration rather than consider justice done. Maybe that’s the rape-com trope. The ultimate hope, of course, is that this film soon feels entirely dated in every way. But with rape prosecutions currently a farce, and #MeToo still rolling news, we’re a long way from a feelgood follow up. C

focusfeatures.com