The future’s so bright | Karim Rashid’s Athenian time warp

Designer Karim Rashid’s first hotel project, Semiramis, opened in Athens in 2004. It looks older – yet is all the bolder for it.

Designer Karim Rashid’s first hotel project, Semiramis, opened in Athens in 2004. It looks older – yet is all the bolder for it.

When I was looking at a shortlist of interviewees for my book Narrative Thread: Conversations on Fashion Collections, I realised there was some colour missing. Literally. I needed to talk to someone who represented the antithesis of my own tastes (black, black, black, and a little dark grey). I knew instantly that person should be Karim Rashid. I’ve worked with Karim on stories for decades, and he has consistently turned up the bright pink and acid green while everyone else is going tonal. He has always been driven by the potential of the future and exploring what it might look like – before there was AI, there was Karim Rashid. And so, after a shoot and interview in his Manhattan penthouse, Karim became Chapter 11.

“Look at Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, which is maximalist from floor to ceiling. I remember in our little suburban house we had a pink bathroom and a green refrigerator”

A month before my book was to be published, it seemed a good time to take a break. I’d never been to the first hotel Karim designed, Semiramis, but it had been on my Bucket List ever since it opened 20 years ago. A slice of sweltering Athens, immersed in a Karim Rashid playground, seemed like where I should be before the book launched in London and New York.

After my visit, that chapter on Karim took on a new dimension. “99% of our world is colourless,” he told me as part of our published conversation. “I grew up in the 1960s, when there was a lot of colour. There was the hippie movement, and tie-dye, and black light posters. It was in fashion but also interiors. Look at Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, which is maximalist from floor to ceiling. I remember in our little suburban house we had a pink bathroom and a green refrigerator. Everyday objects used a lot of colour. I have a theory that as soon as we landed on the Moon, in 1969, and realised that it was just a dead rock, that it made us feel like we had nowhere to go. Until then, the future and everything space age was so positive, we were all going to live on other planets.” Semiramis reads as a kind of artist’s statement in line with this, but from an individual whose roots are in a later decade.

Karim in Narrative Thread: Conversations on Fashion Collections (Bloomsbury)

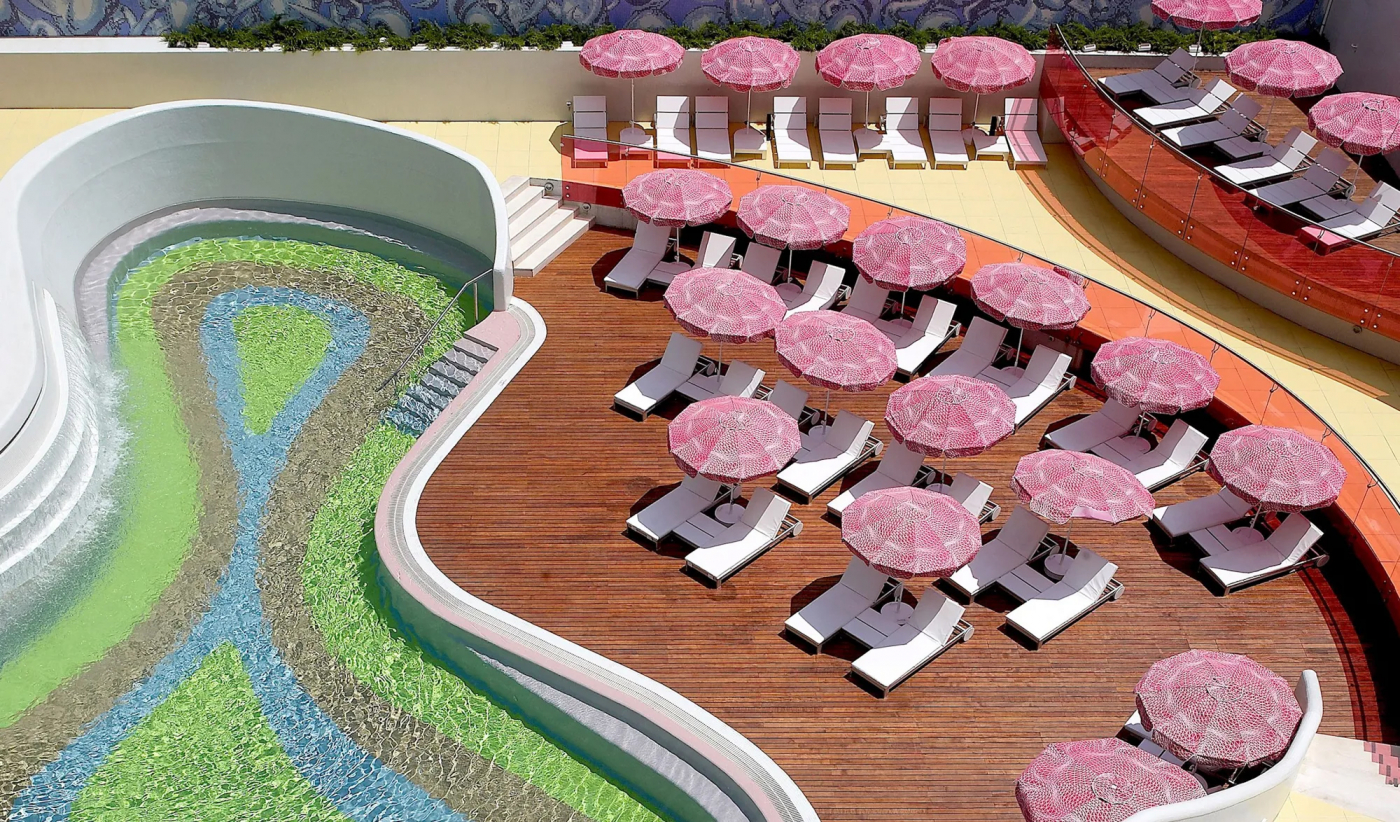

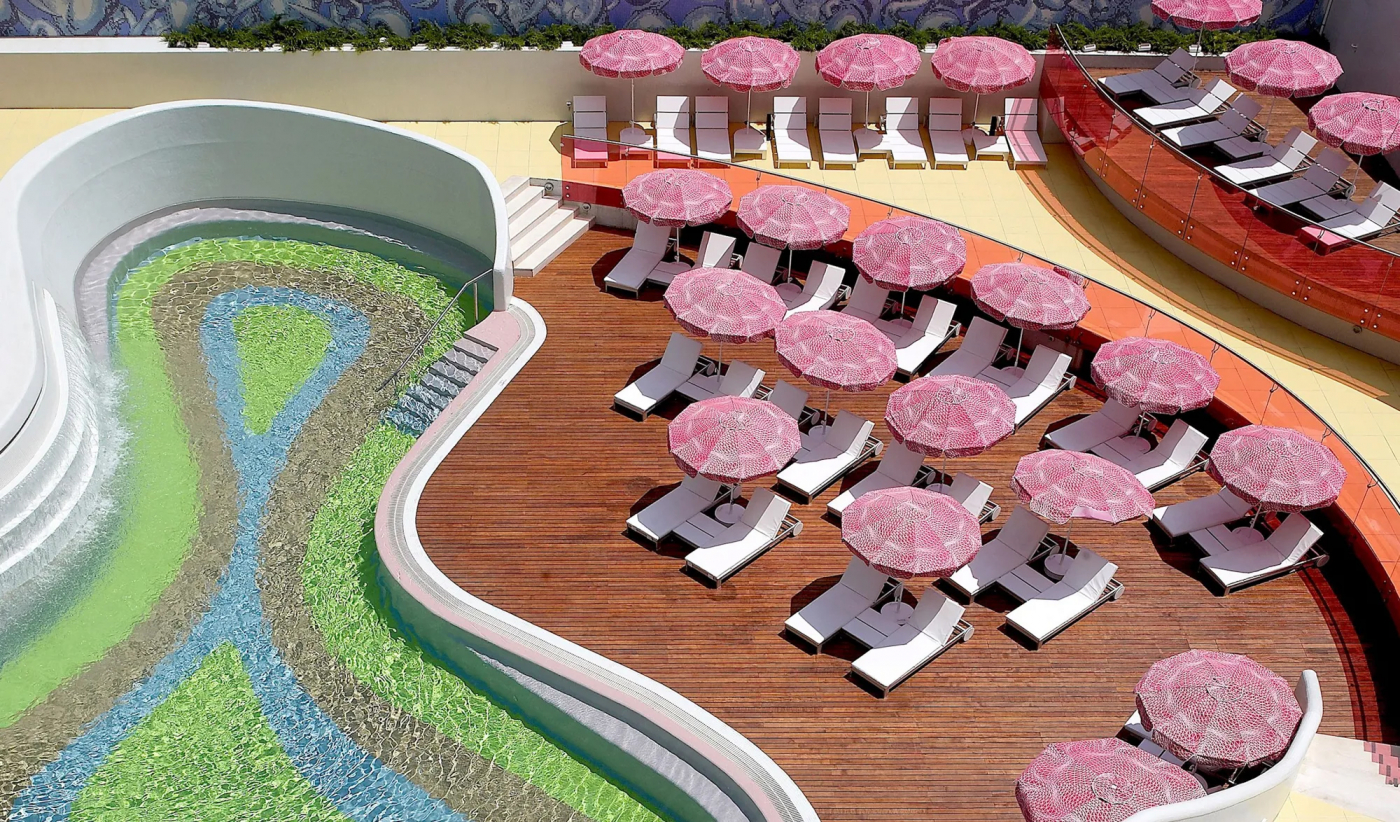

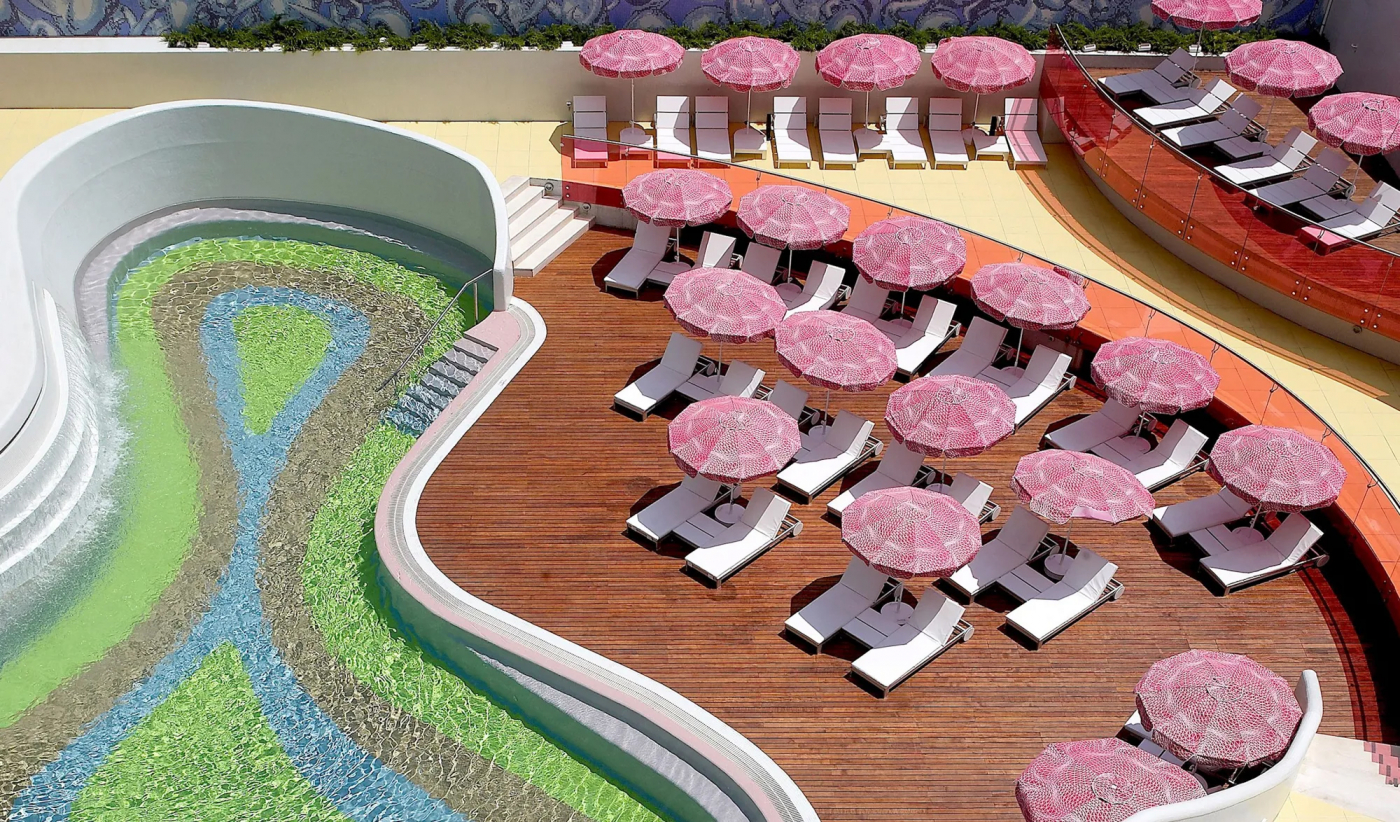

There’s a reason why all the Jetsons-style mosaic swirls at the hotel, and the graphics throughout, make me think of the sleeves of 12-inch remixes and Manchester nightclub flyers from the mid-1990s. The 1980s was the decade of surface and postmodernism (ingrained in Karim’s background through his studies with Ettore Sottsass), but the ten years that followed took a lot of its elements and supercharged them as we lived in anticipation of a new millennium. There was a kind of rave-fuelled excitement (as naïve as it seems now), and Karim was plugged into it as much as anyone else. Semiramis opened in 2004, but its spirit is a few significant years older. Instead of numbers, the rooms and poolside bungalows at Semiramis have symbols, and you get a patch of stickers when you check-in, to attach to any bill instead of using a pen (I hadn’t, somewhat ridiculously, realised this this was the concept, and instead requested a pen and drew my symbol below the total each time I had a glass of wine). My bungalow had a brightly coloured Perspex shower space that could, in theory, be filled to be a bathtub. It wouldn’t have been the most comfortable experience, but it looks fantastic. And it’s so brilliantly 1990s. The pool is an amorphous acid trip, flanked by a giant mosaic wall of what looks like an army of H.R. Giger’s aliens coming into frame.

Semiramis, Athens

My stay at Semiramis made me think about why the 1990s was so crucial to design, and why its visual energy will become cyclical. It was the era of McQueen and Hirst, but also Tom Dixon, Marc Newson and the Campana brothers. Semiramis happened because industrialist Dakis Joannou wanted a hotel in Athens that could also house some of his art collection, and he wanted Karim Rashid to create something that was nothing like a white cube to show it in. When he put the money down, in 2001, it was to create a vestibule for culture from the ten years before the deal was signed.

Semiramis, Athens

One of the key artworks in the lobby is a YE$ illumination by Tim Noble and Sue Webster. The YBAs were still hogging the limelight in the 1990s, but Tim and Sue were the brighter stars. In the 1998 video for ‘Drowned World/Substitute for Love’, Madonna is seen fleeing fans and paparazzi around the hallways of the Atlantic Bar & Grill, Oliver Peyton’s temple to 1990s excess in Piccadilly. As she turns a corner, you can see one of Noble and Webster’s 1996 Excessive Sensual Indulgence fountain-motif neon works. Anyone who remembers the Atlantic will recognise it instantly and be pulled back to moments and misadventures from the past: Peyton’s place, which was open from 1994 until 2005, was the Studio 54 of its time. The year it closed, Sketch had taken over as London’s default multi-roomed playground of design and debauchery. It was also the year that the first easyHotel opened in the capital, creating a pared-back model for budget digs that still influences new brands today.

Semiramis, Athens

Semiramis isn’t the most luxurious hotel in Greece. That’s not its point. And it could do with a solid shift and upgrade in F&B. This is a neighbourhood with money, and a few extra dining options would be welcome. The stage is already here. But the core of the business plan is still evident and solid: snare a designer considered visionary via his radical product design and give him a bigger canvas. If Karim’s acid-pop chairs could command column inches in the design press, then surely a hotel could be sensational. And it is. Today, as part of Yes! and a member of Design Hotels, Semiramis stands as a survivor within a commercial genre of architecture prone to cannibalisation. Like Gio Ponti’s 1964 Parco dei Principi in Sorrento and, despite numerous restorations, Arne Jacobsen’s 1956 SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, it’s of its time, even if it really technically isn’t. As long as it’s looked after, and no one tries to modernise it (leave those ridiculous shower/baths alone!), it will look increasingly interesting with age – radical, even. C

Semiramis Hotel, Char. Trikoupi 48, Kifisia 145 62, Greece

Designhotels.com