Dramatic stories often begin or end with murder, and the life of controversial filmmaker, poet, author, Communist Catholic, gay contrarian Pier Paolo Pasolini couldn’t have been more climactic. 2022 was the centenary of his birth, and Criterion recently released a £120 box set of his remastered films on Blu-Ray. His final work, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, was a favourite of the late Alexander McQueen, as well as Madonna, who once said: “Watch this movie, and if you don’t like it, we can’t be friends.” Many would rather renounce the friendship. The film is as repellent as it is remarkable – a retelling of De Sade crossed with Dante, set in the short-lived fascist Republic of Salò in 1944. A group of radiant youths are captured by a group of four amoral libertines in a remote mansion and tortured until everyone is either dead or insane. In circumstances that reverberated with the film’s tone, Pasolini was murdered, aged 53, in 1975, before Salò’s release. He was and remains an Italian national treasure. Using his life story and death as an unusual guide – from Friuli to Lake Garda, Bologna, Rome and Puglia – takes you to places as rich and fascinating as his films.

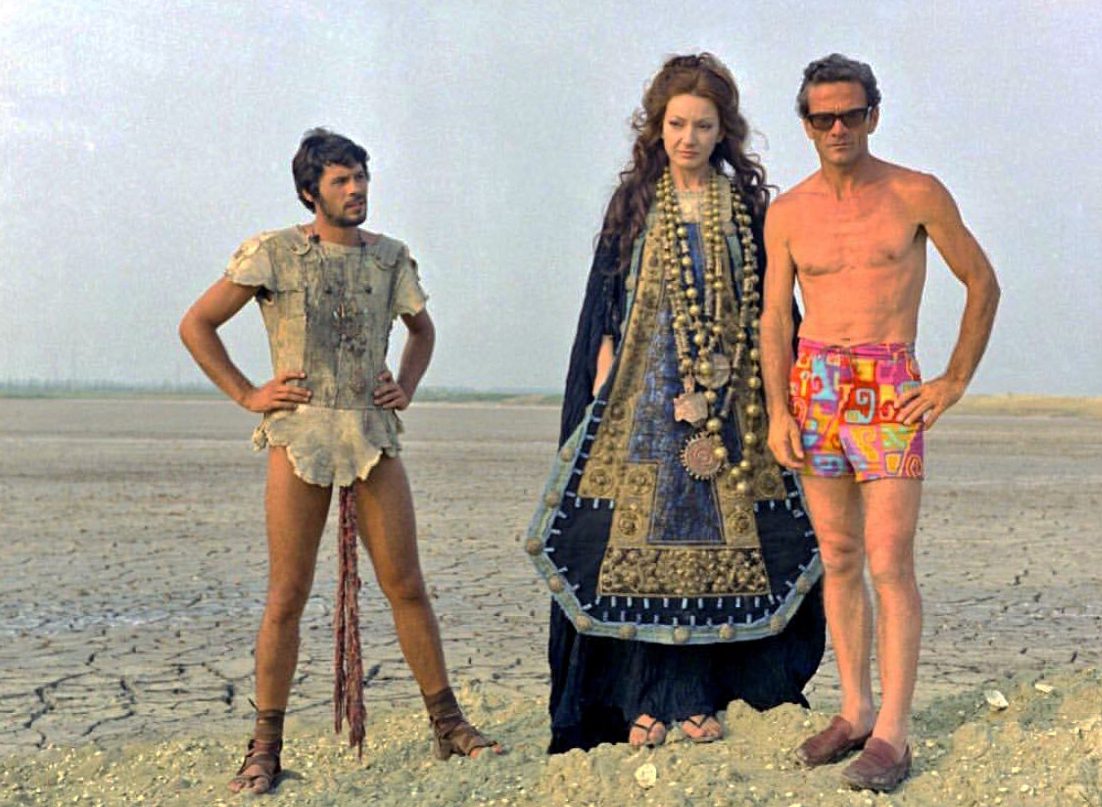

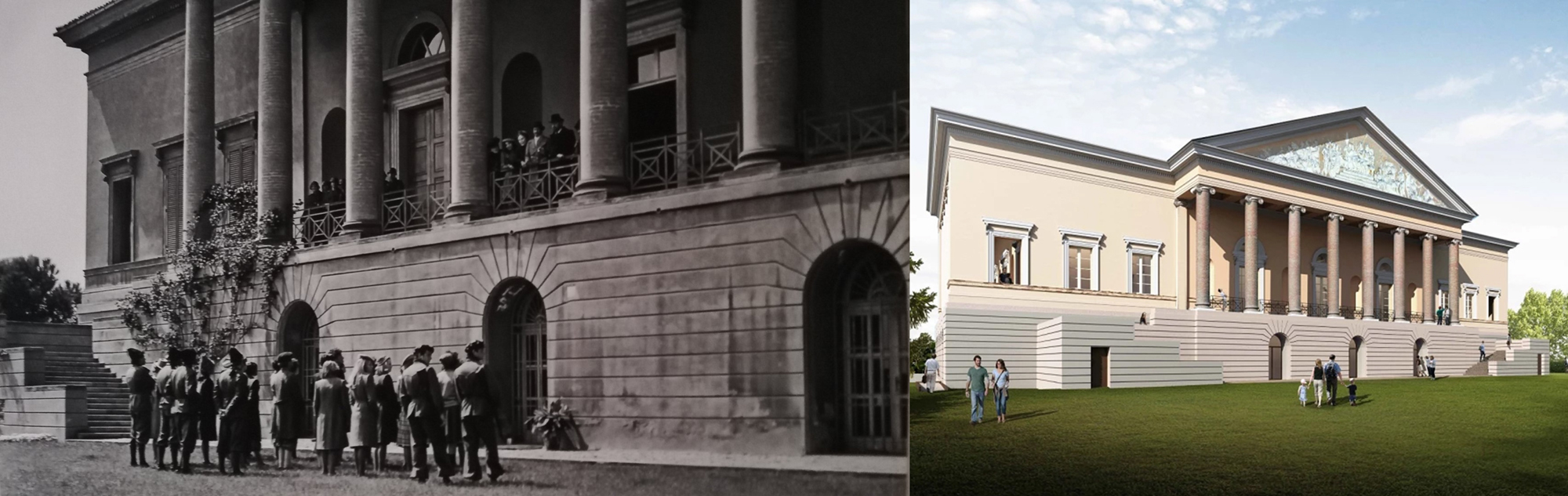

Villa Aldini as seen in Salò, and in the future

A few minutes into the apocalyptic downpour, two girls came out of their hotel and danced a perfect pas de deux in the rain

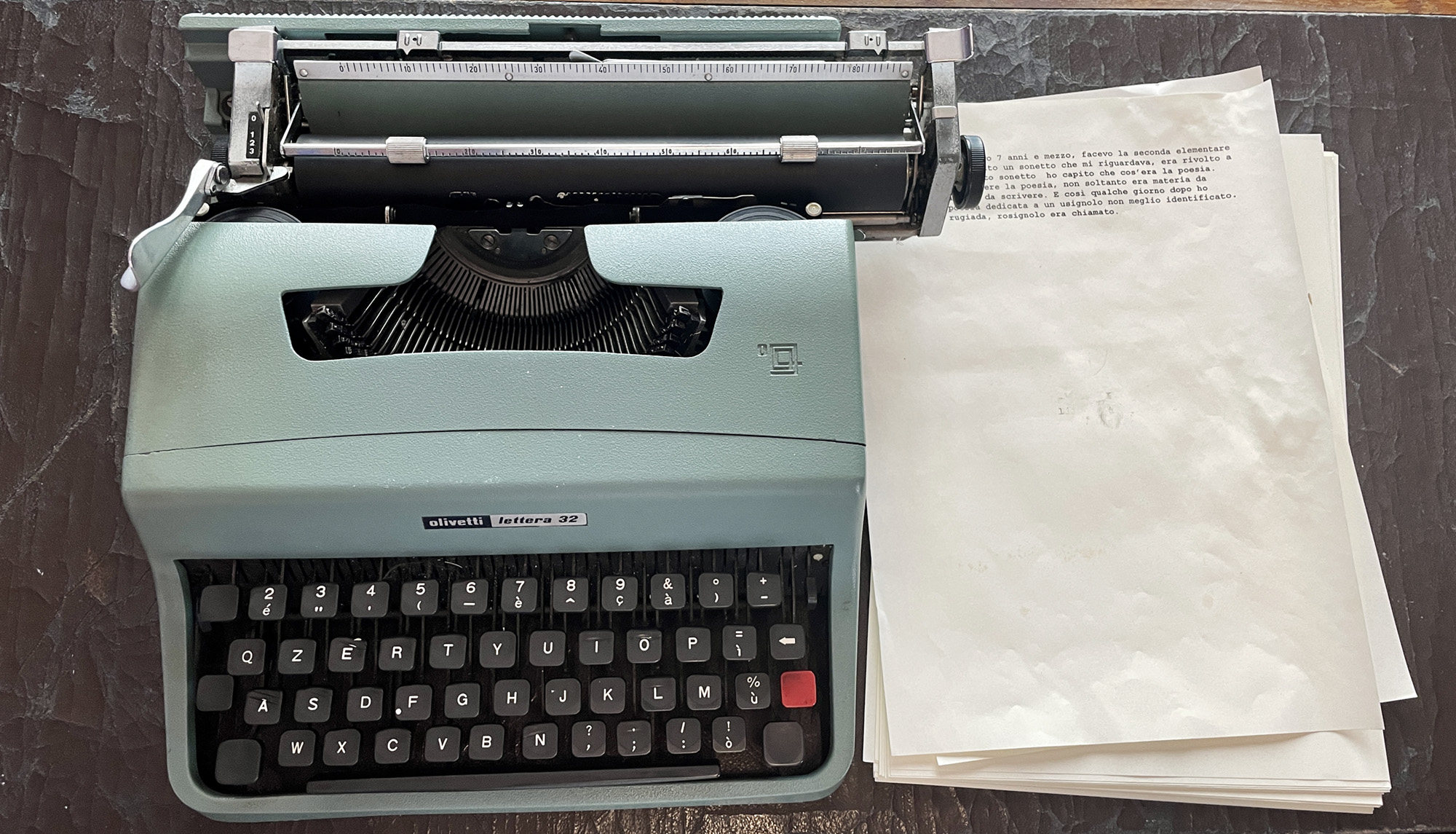

Salò – despite the associations Pasolini’s film gives it – is far from sinister. It’s a glitzy, lakeside tourist town. I had lunch at Villa Feltrinelli – once chez Mussolini, then the setting for an early scene in Pasolini’s most notorious movie. Ravishing doesn’t begin to describe it, with its Venetian meets Moorish silhouettes and exterior candy stripes, and extravagant dining terrace by the water. The cheapest room is €1,700 a night, and a caprese salad is €38, but if I was wealthy, I’d spend all summer here. I stayed, instead, at the chic B&B Panorama Cinque, the polar opposite of Feltrinelli – all cool white modernist interior design. Mussolini would find it too sparse, but I loved it, and rooms start at €130. I dined at Osteria di Mezzo, a handsome old-fashioned place that serves perfect tagliata, and stopped for a nightcap by the lake at Bar Italia. Without warning, a violent thunderstorm descended. I sat drinking wine under cover but outside, marvelling at the town’s transformation. A few minutes into the apocalyptic downpour, two girls came out of their hotel and danced a perfect pas de deux in the rain, lit by flashes of sheet lightning and streetlamps shaped like sculpted pitchforks. It looked like a duet at the end of the world.

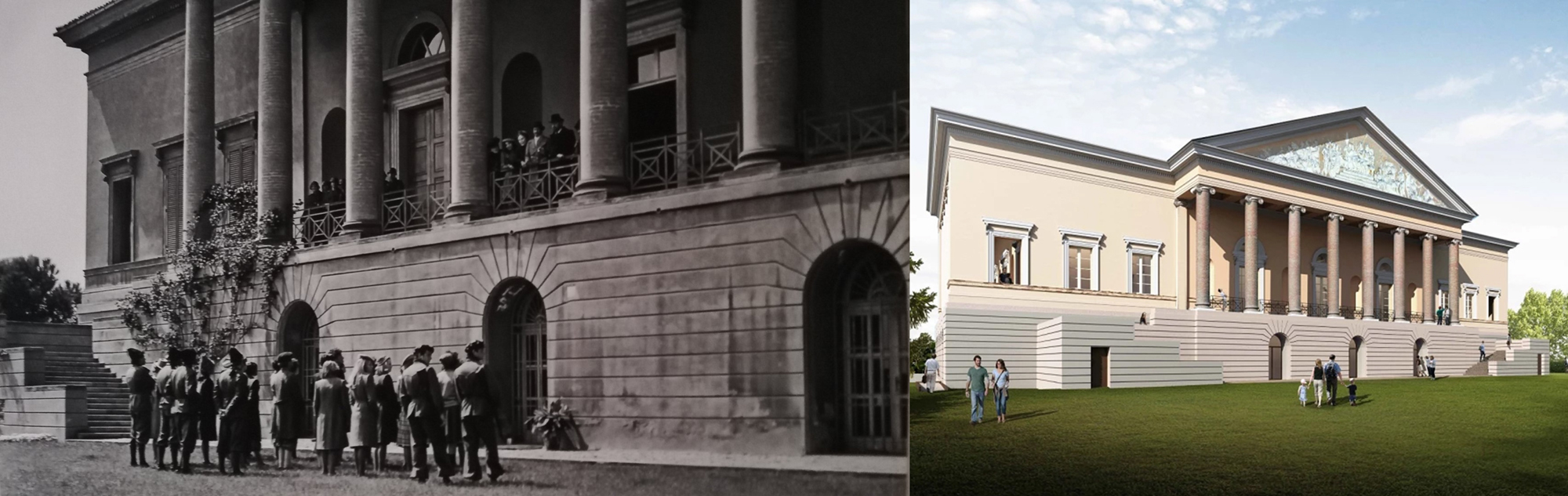

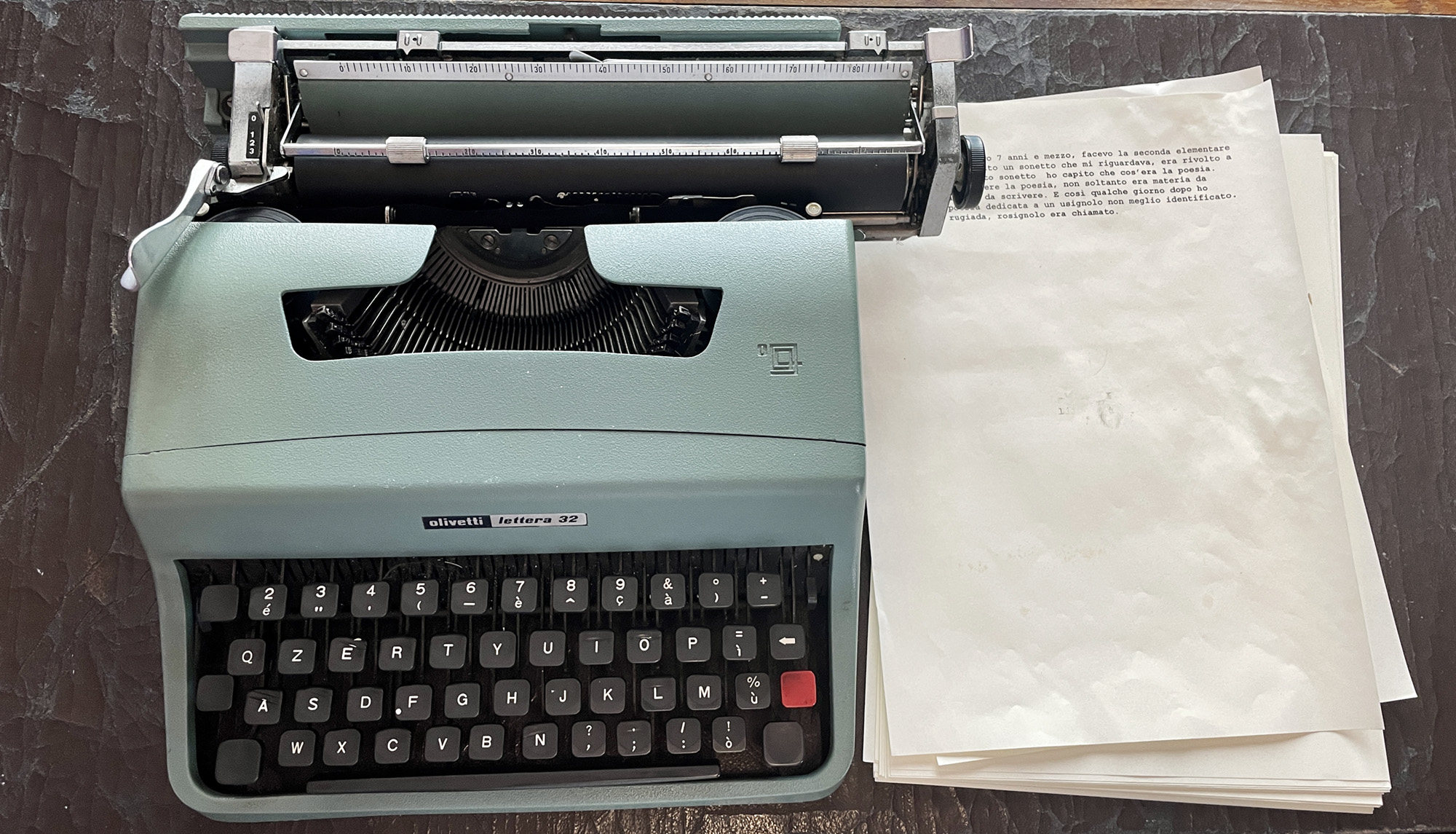

Pasolini’s typewriter at his old house in Casarsa

I started my 10 days of train travel in Casarsa in Friuli, an hour and a half from Venice, where Pasolini grew up. I visited the Centro Studio Pasolini, a museum in his mother Susanna’s old home, which still has her antique furniture. Other artefacts are highly emotive, from Pier Paolo’s typewriter to his early handwritten poems in the Friuli language. The stories about WWII and its torturous effect on Susanna (never seen in public without her scarlet red lipstick) and her husband, are dark. But the museum also tells a story about a family and community that was as close as can be and which represents the roots of Pasolini’s art – from his brother’s brutal death, aged 19, at the hands of the Communist-aligned Garibaldi Brigade to his father’s fascism.

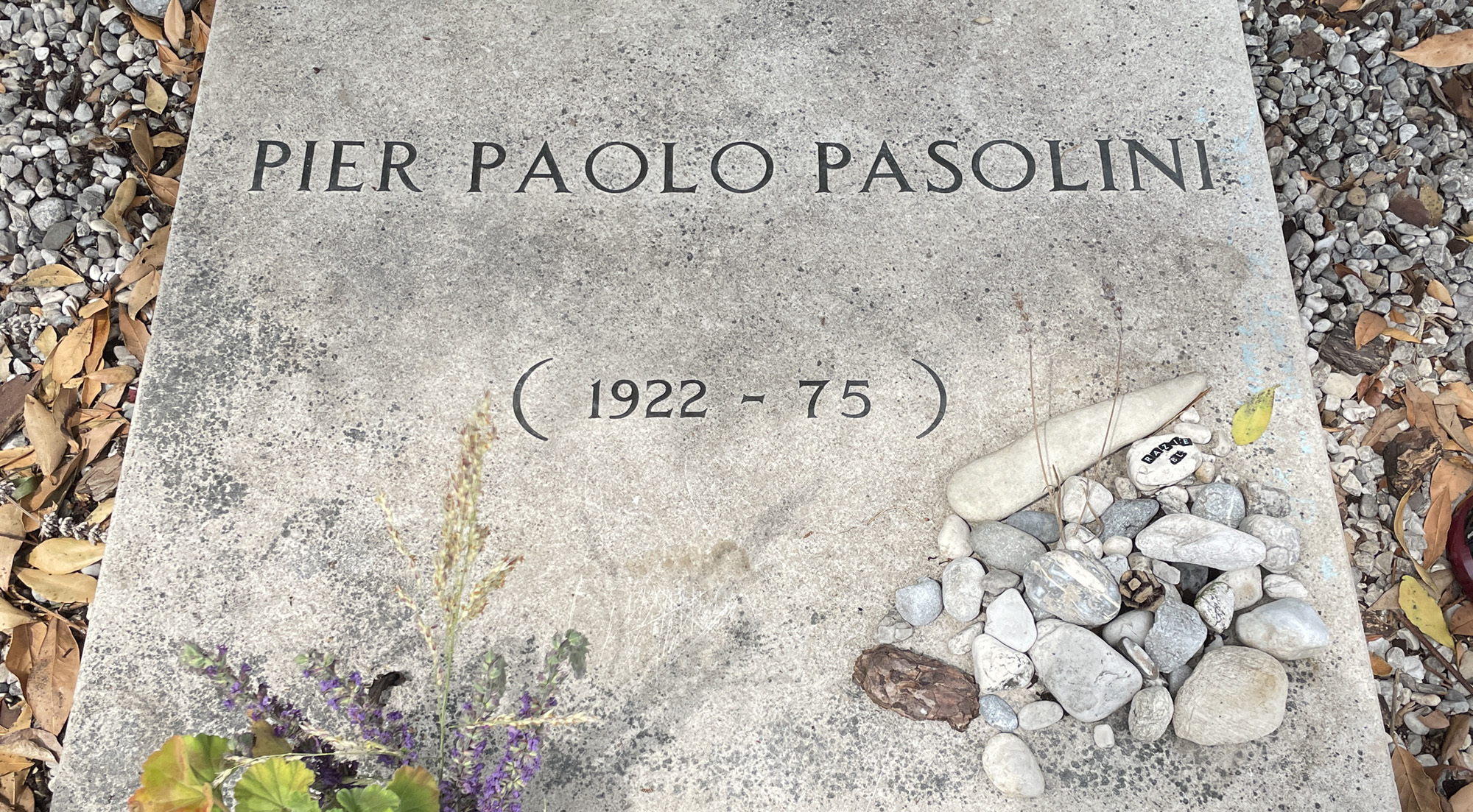

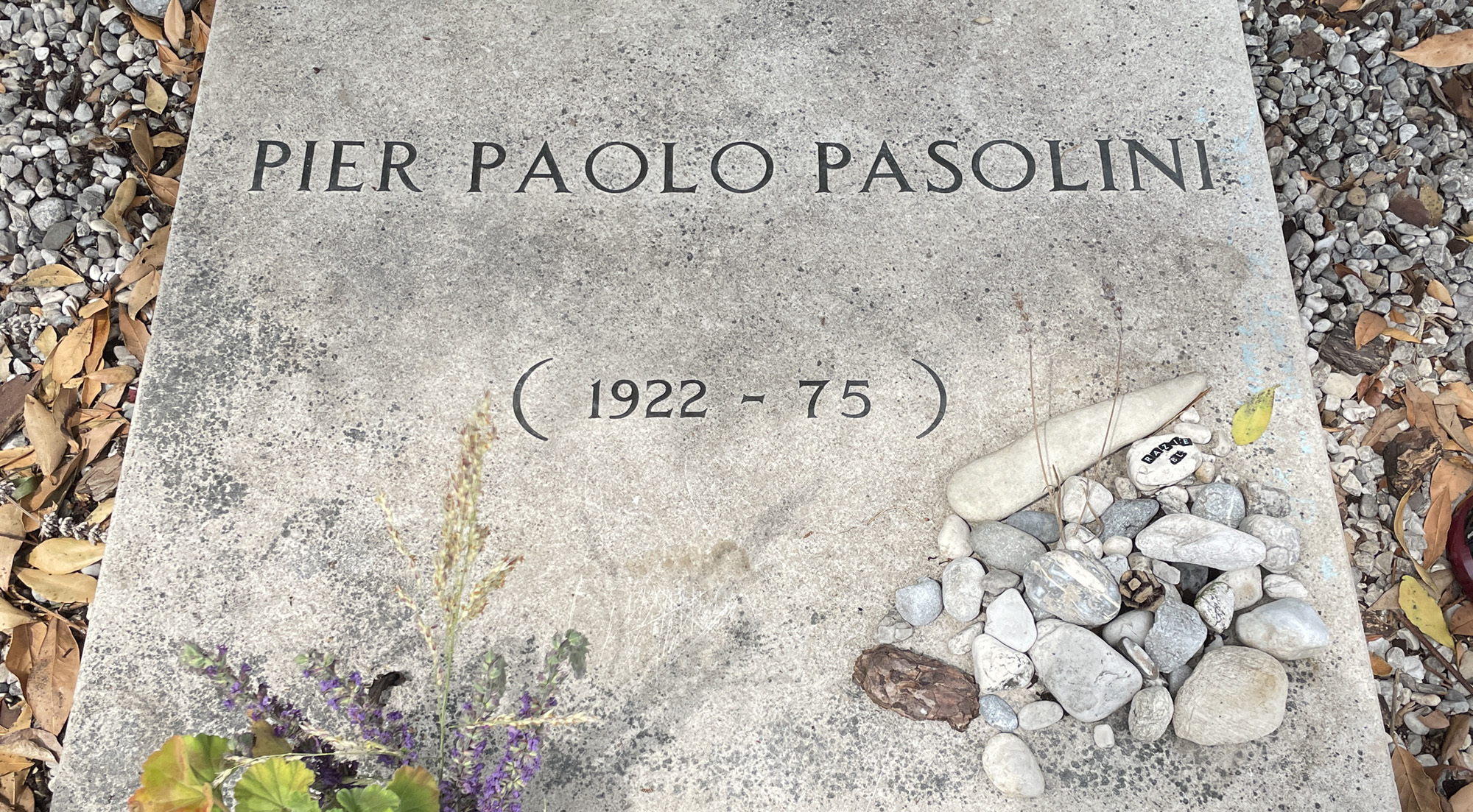

The Centro works with the local tourist office to offer regular guided tours of key Pasolini sites around town, including St Anthony’s Church, where he uncovered ancient frescoes documenting the invasion of the area by Turks in the 15th century. His memorial service was at the nearby Santa Croce and San Rocco, a tiny church which accommodated a fraction of the thousands who wanted to attend, and his body is buried beside his mother’s in the local cemetery. His brother Guido is nearby.

Villa Feltrinelli

Casarsa is small but special – the locals clearly have a deep fondness for the filmmaker (although he was effectively run out of town for “obscene acts” in 1950, which prompted him to move to Rome, into his career in cinema). There’s a scruffy little bar opposite the museum called Agli Amici di Colussi Corrado, serving paninis and delicious Friuli wines at €3 a glass. By the door is a stack of books for sale about Susanna Pasolini.

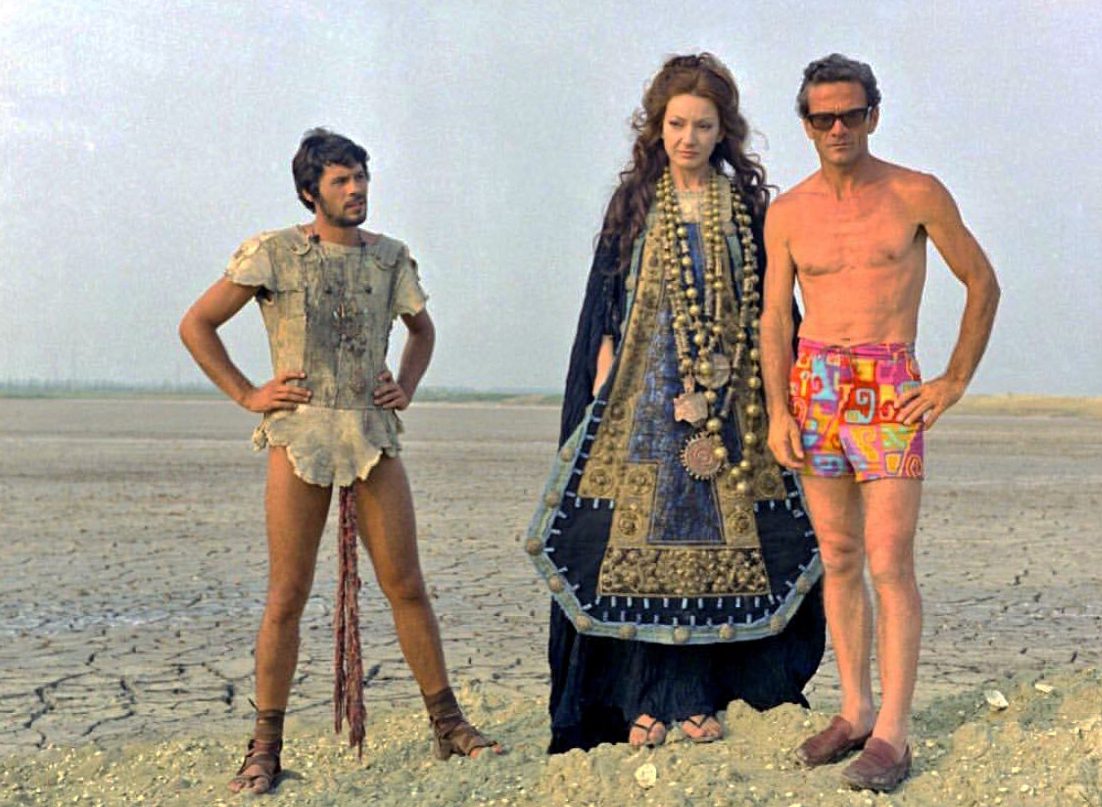

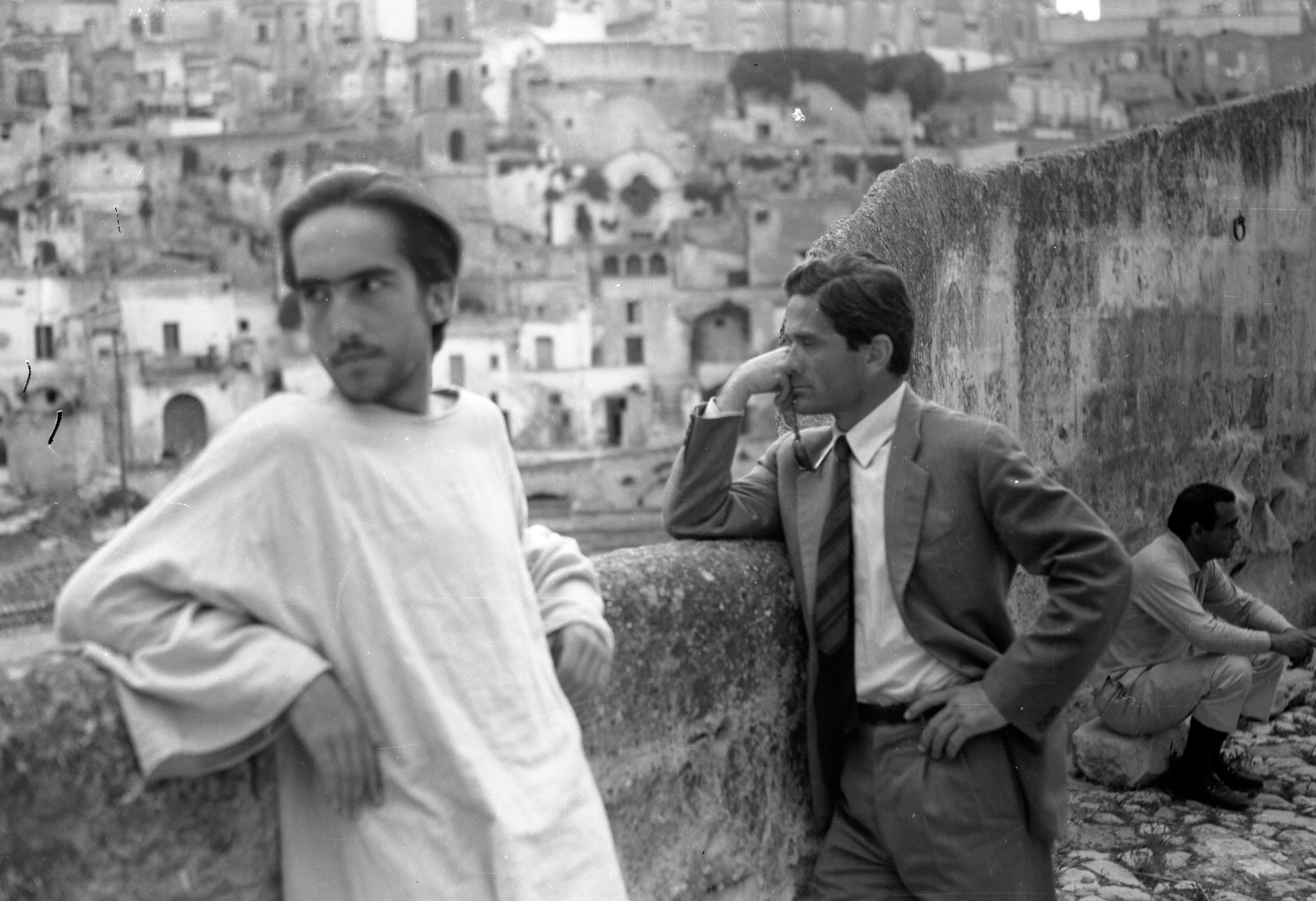

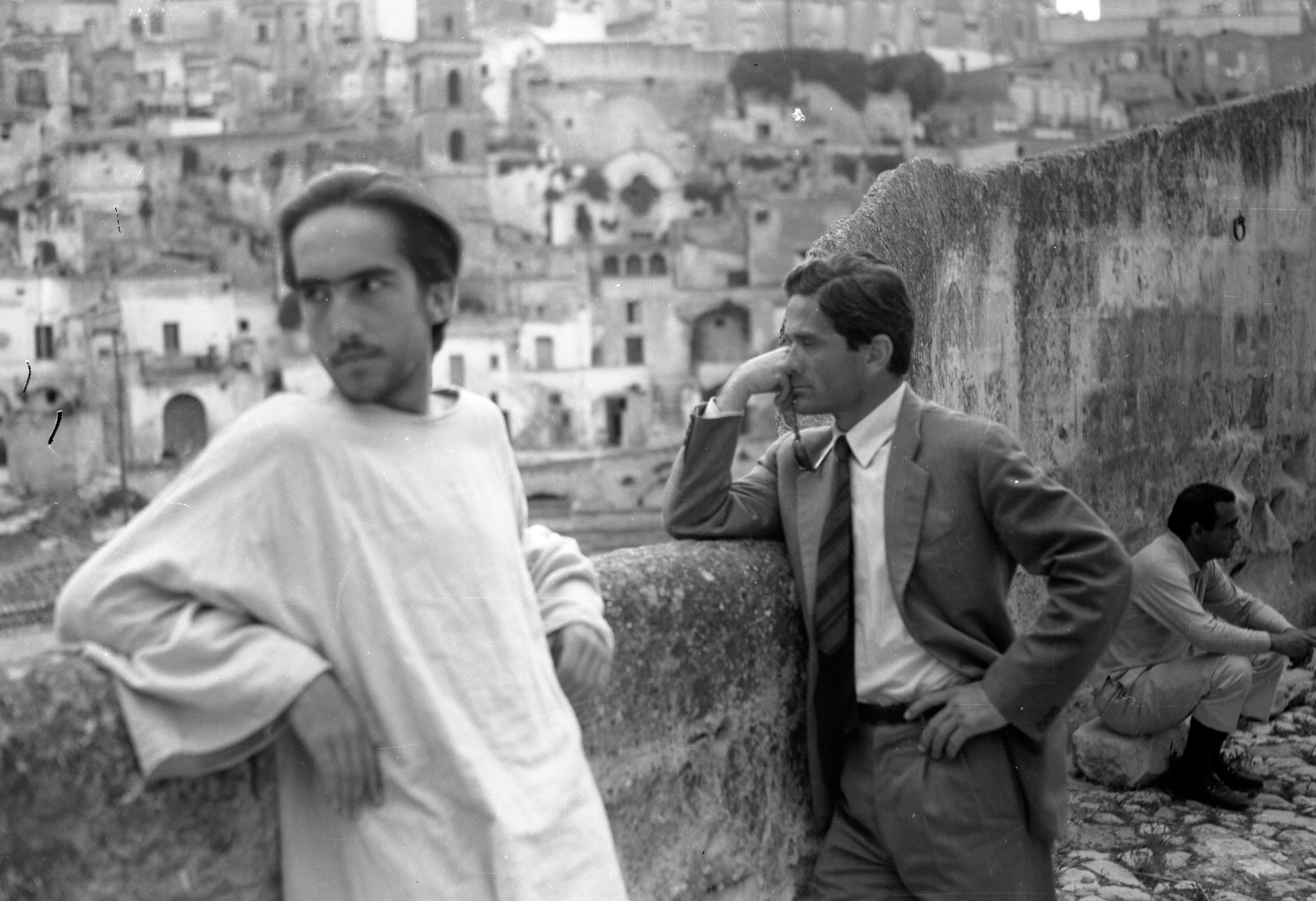

Pasolini on the set of The Gospel According to St. Matthew with lead actor Enrique Irazoqui, by Maurizio Lucidi

While the late genius is most associated with Friuli, he was born in Bologna, known by all as the “red city” for its rooftops and political leanings. It’s a joy to explore: a city dominated by students and real residents, rather than tourists. The restaurants are superb, and there are great terrace bars close to the house Pasolini was born in, at 4 Via Borgonuovo. Most of the exterior shots in Salò were filmed at Villa Aldini, at the top of an exceptionally steep hill, 40 minutes on foot from the centre. The Villa’s gates are currently locked while architectural refurbishments take place – something I wish I’d known before setting off in 34-degree heat to see it. Dejected and sweat-drenched, I ordered a cab back to town, and the driver included a silver lining detour. A few hundred metres down from the Villa is a psychiatric hospital, at whose rear is a garden with panoramic views over the city, enjoyed by couples holding hands on benches at the golden hour.

Pasolini mural in Rome

Back in the city, I visited the Pasolini Archive at the Cineteca Bologna, which has a room devoted to his ephemera, film stills, books and scripts. There are stacks of photos of Terence Stamp in Theorem, while upstairs there’s a huge, fantastically camp photograph on the wall showing the director in gaudy 1970s swimwear next to an opulently dressed Maria Callas on the set of Medea. The archive includes material from one of his few family-friendly films, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, filmed in and around Matera, in the middle of Puglia.

Matera

Matera was inhabited for 9,000 years, with people living in caves cheek by jowl with livestock and no plumbing. Effectively forgotten by the rest of the country and world, the population festered in poverty and disease until the 1950s when the media shamed the government into rehousing everyone in new homes fit for purpose. The emptied caves presented a golden opportunity for Pasolini, whose Jesus and apostles walked through the Sassi districts in 1964. Today (after James Bond’s subsequent visit in 2021) Matera is packed with tourists, but nothing can diminish its beauty. I stayed for two nights in a vast cave at Sextantio – part hotel, part archaeological project. My room was whitewashed and dreamy, a troglodytic fantasia also reminiscent of 14th century folklore, with a brick floor, an ornate wooden bed with gilt flourishes and stern high-backed antique chairs – the set for Pasolini’s Canterbury Tales came to mind. It’s one of the most extraordinary places I’ve ever slept, in a landscape to match.

Turn left on to the street after your negroni to see a mural of a giant eye of Pier Paolo

Pasolini’s story was dominated by, and ended in, Rome, where I spent the most time. I stayed in Soho House in San Lorenzo, one of Pasolini’s most frequented neighbourhoods. I explored the Pigneto area, where he made his first feature, Accatone, about a doomed pimp and his gang of rogues. The area is now full of chic bars, and aperitivi in the garden of Necci dal 1924 (where he was a regular) is still quite the thing. Turn left on to the street after your negroni to see a mural of a giant eye of Pier Paolo, then double back to see another painting of him in profile, along with the legend “Don’t deceive yourself, passion never gets forgiveness”. Back at Soho House – the default social hub for the film industry – I cooled off in the rooftop pool while producers from Cinecittà sipped cocktails and scores of pretty young men lounged around, draped over one another on giant sun loungers. If Pasolini was alive today, this is where you’d find him.

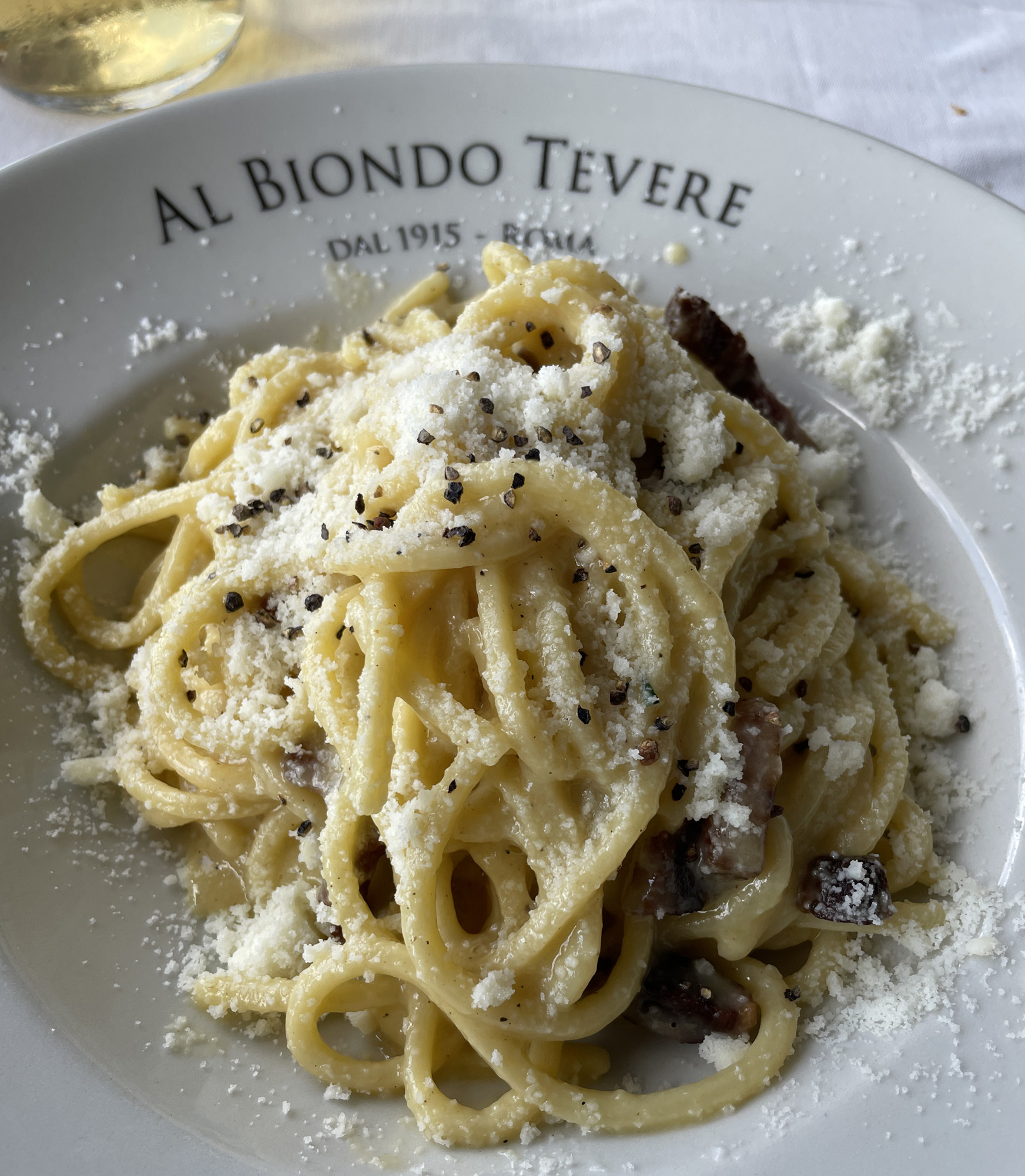

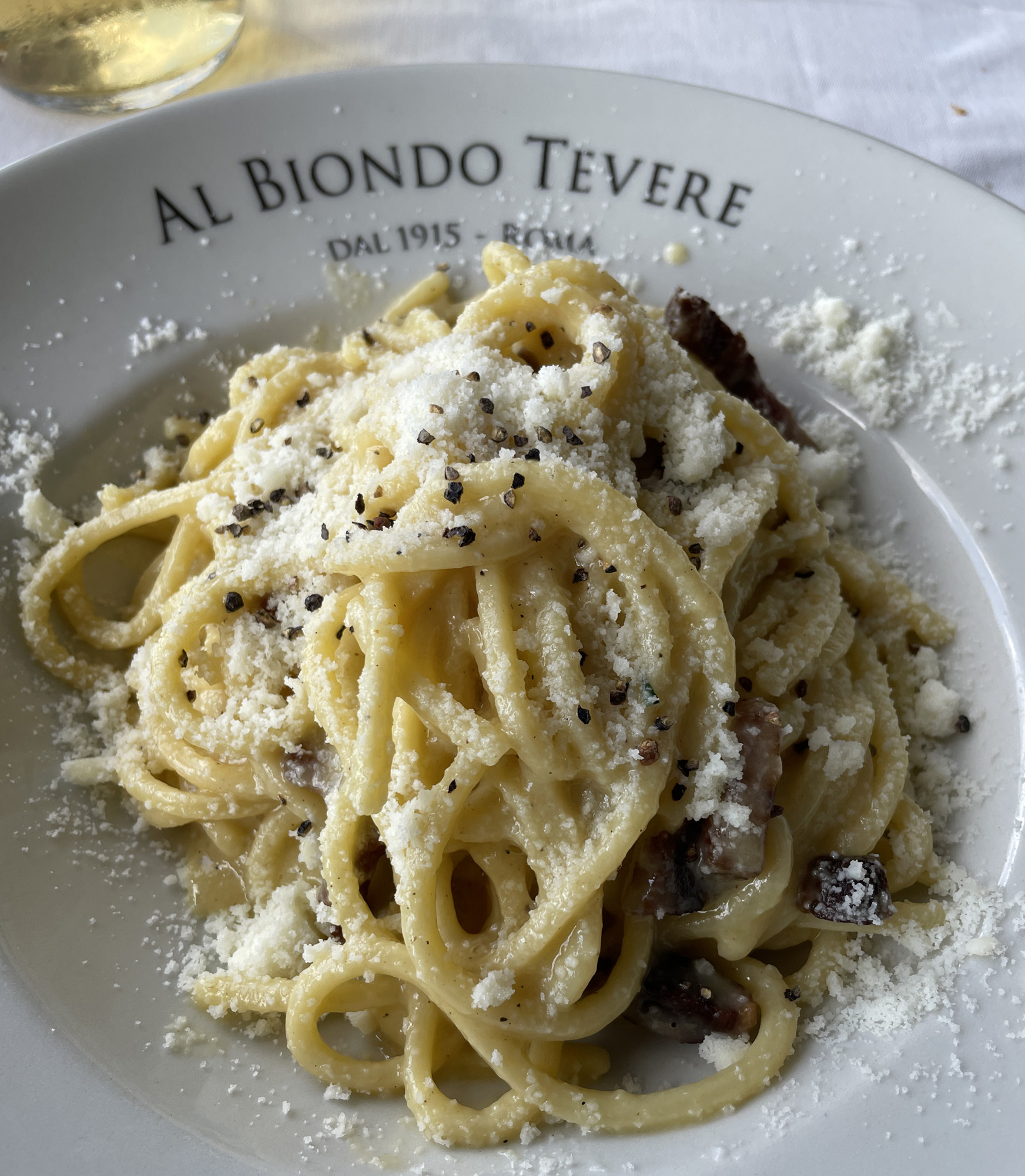

Al Biondo Tevere, Rome

After reading Enzo Siciliano’s biography of the filmmaker, I worked out that one unnamed restaurant the director frequented is Trattoria Priscilla, still a local favourite. The manager speaks perfect English with wit: “Red or white? Half a litre? A litre? Five!?” The pasta is good, the saltimbocca better. The most famous restaurant linked to the filmmaker is where he had his final supper: Pommidoro is on a corner two streets from Soho House, and you can book his usual table – furthest right, closest to the door. The place has been run by the Clementina family for five generations and is renowned for its peppery carbonara (on his Searching for Italy TV show, Stanley Tucci called it the best in town). Alessandra Clementina was there, aged 14, the night Pasolini paid his final bill (the uncashed cheque is framed on the wall). She remembers him saying goodbye to her father Aldo. “Something was very off,” she told me. “He was anxious. He told my father to get out of Italy as soon as possible. My father shrugged and said: ‘You make films everywhere, I make carbonara here’.”

Pasolini’s grave, Cimitero della Casarsa

I retraced the journey Pasolini made in his final hours but saved the finalé for the following afternoon. I went for cacio e pepe at Al Bionde Tevere, which has a pretty rear terrace next to the Tiber. On a wall inside the restaurant there’s a mural of the auteur carrying his own battered lifeless body. This is the place he went after Pommidoro, taking a male hustler he’d picked up at the railway station for a drink before driving out to the coast at Ostia where the boy apparently killed him, battering him unconscious and then driving over his body before escaping in Pasolini’s own Alfa Romeo.

The author at Pasolini’s monument, Ostia

There was a petition in 2023 to have the case reopened and old DNA samples examined – many believe the filmmaker was the victim of a politically motivated assassination, and it’s long been established that more than one assailant was present. There are dozens of theories. One involves the theft of reels from Salò. Was the trip to Ostia as an attempt to retrieve them? The truth is unlikely to ever be established, which just contributes to the drama and myth.

The spot where the director’s body was found is marked by a beautiful, white, modernist marble statue of two doves by Mario Rosati. It feels like the middle of nowhere, and an hour spent here, in total silence despite the proximity to the buzzy Lido di Ostia, is a profoundly calming, albeit melancholy experience. When my taxi picked me up, the driver asked me why I was there, so far from everything. “Pasolini,” I replied. He looked at me in the rear-view mirror solemnly and nodded. “Of course.” C

A version of this story first appeared in The Times on 30th March 2024.

Research was supported by was supported by Friuli Venezia Giulia Tourism (turismofvg.it) and Emilia Romagna Turismo (emiliaromagnaturismo.it).